Maurice Brazil Prendergast

American, born Canada

(St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada, 1858 – 1924, New York, New York)

Maurice Prendergast received general recognition by the American art world only after his affiliation with “The Eight” in their celebrated exhibition at Macbeth Galleries in New York in 1908. Prendergast exhibited alongside urban realists Robert Henri, William Glackens, John Sloan, George Luks and others. The show traveled around the country, earning the group the nickname: “The Eight.” A major force of integrating modern art into America, Prendergast was a member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors which organized the famous Armory Show of 1913. The artist was on the selection committee for American art and the exhibition played a major role in the introduction of modern art to the American audience. Prendergast as an artist has commonly been thought of as a decorative colorist, a creator of idyllic pastorals when in fact in the beginning he was an urban genre painter. Prendergast captured the leisure activity of people in urban surroundings, subject matter that derived from Impressionism. Differing from his Ashcan School contemporaries, Prendergast retained the Impressionist palette in his works. Like his colleagues, the artist found “truth of reality in unpremeditated and unguarded movement, the fleeting image, and the commonplace event.”(1)

On October 10, 1858, Maurice Brazil Prendergast, and his twin sister, Lucy Catherine, were born and baptized in St. John’s, Newfoundland.(2) Two more children were born to Maurice’s parents, Mary and Maurice Prendergast, Sr.: Richard Thomas in 1860 and Charles James in 1863. Maurice’s family was a typically middle class and his father ran a general merchandise store. In 1868, the family moved to Boston, however, financial difficulty prevented the boys from attending school past the age of fourteen. At that time, both Maurice and Charles went to work, both gravitating towards the visual arts. His first job was at Loring and Waterhouse, a dry goods shop where he wrapped packages. Van Wyck Brooks later gave a romantic account of the artist’s youth: “He always had a pencil in his hand, and, whenever he could spare a moment from the paper and string, he sketched the women’s dresses that stood about the shop. Nothing amused his eye more than a pretty dress, blue, green, yellow, or old rose, as one saw in the pictures to the end of his life, the beach parties and fairy-tale picnics with their charming wind-blown figures and little girls with parasols and flying skirts.”(3) The artist’s second job was at a show card shop where he learned lettering, graphic design, and illustration. He began to practice art on his own with no formal training, and in 1886, Maurice and Charles were able to visit England and Wales for the first time.

In 1891, Maurice and Charles arrived in Paris, where Maurice began studying at the Academie Julien at the late age of thirty-one. His instructors were Jean-Paul Laurens, Joseph-Paul Blanc, and Benjamin Constant. He may have also enrolled at the Academie Colarossi where he would have studied with Gustave Courtois. The earliest discernible influence of his art was the then current style of Art Nouveau. For example, "Lady with Umbrella" (c. 1891-94, Terra Museum of American Art) is a monotype of a fashionable Parisian lady. She wears a fancy dress with feathered scarf, a lady’s hat, and holds an umbrella. She is somewhat flat (partially due to the fact that there is no background, she merely “floats” on the paper) and recalls well-known Art Nouveau prints from the period. Not surprisingly, contemporary French styles such as the work of Nabis artists Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis had an additional influence on Prendergast’s work. He was also impressed by Whistler, and influenced by the two-dimensionality of Japanese prints that were then in vogue among collectors and artists in Paris.

Prendergast became a part of the American art circle at the Montparnasse café, "Chat Blanc," where he was acquainted with a progressive segment of contemporary art. Surprisingly, according to art historian Carol Clark, Prendergast seemed unaware of the Post-Impressionist works of Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. Only after his return from Europe did his art begin to take shape.

In late 1894 or early 1895, Prendergast returned to Boston, a fully matured artist and the works of this period marked the beginning of his personal style. A vast majority of Prendergast’s works deal with crowds or groups of people. They have a very particular character—they are anonymous, but individuals, as each are doing something of their own or within the context of the group. Prendergast’s treatment of space was conditioned by lessons he learned in Paris-spatial ambiguity. Prendergast’s best known paintings from this period are of Franklin Park and the South Shore near Boston. In these works, the genteel class are often portrayed in leisure activities, strolling through the park or relaxing by the water. They are commonly dressed in fine clothes, and are predominantly women and children. Prendergast’s figures lack definition; each shape is formed by masses of color, a characteristic that was certainly influenced by the Nabis. However, the lack of dark contour lines sets Prendergast apart from the modern French painters.

Further, although Prendergast painted out-of-doors, he was not a plein-air painter like the Impressionists. All of his pictures were adapted from sketches done on the spot, some themes were repeated while others were worked and reworked. As a result, most of his locations are easily identifiable. The artist’s later work was also typically spatially ambiguous, another trait adapted from his studies abroad. His images were not “flat,” but again lacked the clear definition of traditional perspective. One of Prendergast’s greatest talents was reconciling these themes and characteristics from contemporary art and unyieldingly adapting them to his own style.

Around 1898, financed by his patron Sarah Choate Sears, Prendergast traveled to Italy, spending about eighteen months abroad. He traveled extensively throughout Italy, including Venice, Padua, Siena, Florence, Naples, and Rome. In the spring of 1899, Prendergast sent finished watercolors to the annual Boston Water Color Club exhibition and then in a one person show at the Eastman Chase Gallery. The works were immediately sought by collectors and dealers and continue to this day to be the most treasured of his works. For example, "Splash of Sunshine and Rain" (1899, Collection of Alice M. Kaplan) is a magnificent depiction of St. Mark’s square in Venice. Prendergast captured the moment perhaps after a spring shower as the sun has emerged-the reflection of the cathedral in the water covering the square is a delightful illusion. Prendergast’s success in Boston quickly spread to New York. William Macbeth, an ambitious young dealer contacted Prendergast and arranged to be his dealer for the next decade, bringing the artist national recognition.

By 1900, New York had become the center of the American art world, and its extraordinary growth and social dynamism at the turn of the century made all other American cities pale in comparison. In March of 1900, a solo exhibition of Prendergast’s monotypes and watercolors was held at the Macbeth Gallery. The artist was immediately ranked among the important new artists of the city. He began to exhibit with urban realists Robert Henri, William Glackens, George Lukes, and John Sloan-who would later be referred to as the Ashcan School. He also became close friends with Arthur B. Davies.(4)

Prendergast began seeking similar sites in the United States that he had painted in Italy-tourist locales such as urban palaces, churches, and parks-places where he found large crowds spending leisure time. Central Park in New York City became a favorite spot. Opened in 1858, Central Park was first and foremost an equestrian park. Covering almost 900 acres, it’s miles of paved road were designed more for horse-power than for the casual stroll. When the carriage drives were completed in 1863, the majority of visitors were drawn there by horses. According to art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews, the presence of such a superior facility for carriages stimulated the private ownership of horses and rigs in New York, an expense that was far beyond the reach of the average citizen. Such excessive spending on carriages made Central Park the site of the most conspicuous display of wealth to be found in the city.(5) Prendergast often captured these displays in works such as "Central Park" (c. 1901, Whitney Museum of American Art).

As Prendergast’s career progressed, he continued to experiment with spatial ambiguity. His most constant compositional device was “banding,” or the horizontal stacking of formal units. For example, in the Museum’s "A Dock Scene" (c. 1900-05), Prendergast divides the action into three bands: the barges in the harbor in the foreground, the people milling about the dock in the middle, and the water and Boston cityscape in the background. “Trelllising” is another device he uses in which elements anchored in the lower bands of the composition extend to the upper bands as in "Summer’s Day (Summer, Summer Days)" (c. 1918-23, Whitney Museum of Art), in which trees extend from the first band into the second band in the background, thus connecting the composition. His third device was “climbing perspective” where figures were placed vertically, as if climbing a hill or seen from an elevation. This, coupled with spreading the figures over most of the surface achieved a tapestry-like effect, as in "Summer Outing on the Rocks (Nantasket)" (c. 1903-05, Private Collection).

Having recently escaped from site-specific scenes, Prendergast was profoundly influenced by art he had seen during a summer trip to Paris in 1907. He absorbed the radical styles of Cezanne, the Neo-Impressionists, and Matisse’s Fauves. Their anti-naturalist color and subject matter appealed to the American artist and he soon adapted them to his style. For example, "Bathers by the Sea" (c. 1910-13, Williams College Museum of Art) is his interpretation of the modern goddess and his first attempt to use the female nude in his work. In the painting, a group of nude women gather at the water’s edge. The composition is compressed, with land in the immediate foreground and water occupying most of the scene. The work is loosely rendered, giving the sense that elements are stacked on top of one another as opposed to receding naturally into the background.

In 1908, Prendergast exhibited with Robert Henri and the other urban artists in an exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries. The show became an event, traveling around the country, and earned the group the nickname of “The Eight.” According to Mathews, Henri’s philosophy of modern art was tied to the modernity of American life, specifically in New York. Prendergast shared these ideals, but with his next venture to Europe, his ideas began to change.

Prendergast’s acceptance into the New York art scene was due to the large amount of respect younger artists held for him. Having experimented in representing modern life for nearly twenty years, and his enthusiasm for spectacle made him like-minded in their eyes. By 1914, he found himself exhibiting alongside Dada artist’s Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Although he did not adapt the Dadaist notion of chance into his art, Prendergast respected his colleagues all the same. In 1917, both he and Charles exhibited in the famous Society of Independent Artists where Duchamp revealed his famous ready-made “sculpture,” "Fountain" (1917).(6)

Prendergast continued to paint until his death from prostate cancer in 1924. His later works were idyllic park and beach scenes, “echoing Renoir’s bathers and Puvis de Chavanne’s atmospheric historicism and ancient friezes (most commonly, Egyptian and ancient Greek). Mathews wrote of the artist, “Prendergast did not live to see an American society in which leisure became the hallmark of modern life as he had once imagined it would; instead he lived as the more typical American of the twentieth century-working until ill health or death brought a much needed respite.”(7)

1) Carol Clark, et al. Maurice Brazil Prendergast and Charles Prendergast: A Catalogue Raisonne, Munich: Prestel, 1990: 17.

2) Nancy Mowll Mathews, The Art of Leisure: Maurice Prendergast in the Williams College Museum of Art. Columbus: Excelsior Printing Co., 1999: 8. According to family records, Lucy Catherine died when she was around eighteen years old. Prendergast’s early life is sketchy.

3) Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachussetts, 1938, Retrospective Exhibition of the Work of Charles and Maurice Prendergast (exhibition catalogue with “Anecdotes of Maurice Prendergast” by Van Wyck Brookx): 33; quoted in Cecily Langdale, Monotypes by Maurice Prendergast in the Terra Musuem of American Art (Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 1984): 9.

4) All of the aforementioned artists are in the Museum’s collection.

5) Mathews, 29-31.

6) Duchamp’s "Fountain" was acquired from J. L. Mott Iron Word, a manufacturer for plumbing equipment. Before exhibiting the piece, the artist rotated the urinal ninety degrees from its normal, functional position, and left it unembellished except for the inscription “R. Mutt 1917”-a pseudonym that synthesized the name of the manufacturer and that of the popular comic strip “Mutt and Jeff.” The original Fountain has long since disappeared. In 1964, Duchamp entrusted the Galleries Schwartz in Milan with the production of a signed and numbered edition of his most important ready-mades. Each was fabricated to replicate the original and the edition for each was limited to eight. One can be found at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

7) Ibid, 47.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 5/17/04

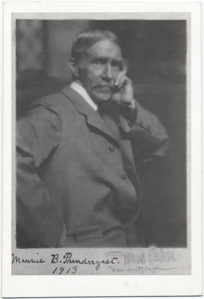

Image credit: Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852–1934), Maurice Prendergast, 1913, photographic print, Macbeth Gallery records, 1947–1948, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Photograph courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

American, born Canada

(St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada, 1858 – 1924, New York, New York)

Maurice Prendergast received general recognition by the American art world only after his affiliation with “The Eight” in their celebrated exhibition at Macbeth Galleries in New York in 1908. Prendergast exhibited alongside urban realists Robert Henri, William Glackens, John Sloan, George Luks and others. The show traveled around the country, earning the group the nickname: “The Eight.” A major force of integrating modern art into America, Prendergast was a member of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors which organized the famous Armory Show of 1913. The artist was on the selection committee for American art and the exhibition played a major role in the introduction of modern art to the American audience. Prendergast as an artist has commonly been thought of as a decorative colorist, a creator of idyllic pastorals when in fact in the beginning he was an urban genre painter. Prendergast captured the leisure activity of people in urban surroundings, subject matter that derived from Impressionism. Differing from his Ashcan School contemporaries, Prendergast retained the Impressionist palette in his works. Like his colleagues, the artist found “truth of reality in unpremeditated and unguarded movement, the fleeting image, and the commonplace event.”(1)

On October 10, 1858, Maurice Brazil Prendergast, and his twin sister, Lucy Catherine, were born and baptized in St. John’s, Newfoundland.(2) Two more children were born to Maurice’s parents, Mary and Maurice Prendergast, Sr.: Richard Thomas in 1860 and Charles James in 1863. Maurice’s family was a typically middle class and his father ran a general merchandise store. In 1868, the family moved to Boston, however, financial difficulty prevented the boys from attending school past the age of fourteen. At that time, both Maurice and Charles went to work, both gravitating towards the visual arts. His first job was at Loring and Waterhouse, a dry goods shop where he wrapped packages. Van Wyck Brooks later gave a romantic account of the artist’s youth: “He always had a pencil in his hand, and, whenever he could spare a moment from the paper and string, he sketched the women’s dresses that stood about the shop. Nothing amused his eye more than a pretty dress, blue, green, yellow, or old rose, as one saw in the pictures to the end of his life, the beach parties and fairy-tale picnics with their charming wind-blown figures and little girls with parasols and flying skirts.”(3) The artist’s second job was at a show card shop where he learned lettering, graphic design, and illustration. He began to practice art on his own with no formal training, and in 1886, Maurice and Charles were able to visit England and Wales for the first time.

In 1891, Maurice and Charles arrived in Paris, where Maurice began studying at the Academie Julien at the late age of thirty-one. His instructors were Jean-Paul Laurens, Joseph-Paul Blanc, and Benjamin Constant. He may have also enrolled at the Academie Colarossi where he would have studied with Gustave Courtois. The earliest discernible influence of his art was the then current style of Art Nouveau. For example, "Lady with Umbrella" (c. 1891-94, Terra Museum of American Art) is a monotype of a fashionable Parisian lady. She wears a fancy dress with feathered scarf, a lady’s hat, and holds an umbrella. She is somewhat flat (partially due to the fact that there is no background, she merely “floats” on the paper) and recalls well-known Art Nouveau prints from the period. Not surprisingly, contemporary French styles such as the work of Nabis artists Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis had an additional influence on Prendergast’s work. He was also impressed by Whistler, and influenced by the two-dimensionality of Japanese prints that were then in vogue among collectors and artists in Paris.

Prendergast became a part of the American art circle at the Montparnasse café, "Chat Blanc," where he was acquainted with a progressive segment of contemporary art. Surprisingly, according to art historian Carol Clark, Prendergast seemed unaware of the Post-Impressionist works of Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh. Only after his return from Europe did his art begin to take shape.

In late 1894 or early 1895, Prendergast returned to Boston, a fully matured artist and the works of this period marked the beginning of his personal style. A vast majority of Prendergast’s works deal with crowds or groups of people. They have a very particular character—they are anonymous, but individuals, as each are doing something of their own or within the context of the group. Prendergast’s treatment of space was conditioned by lessons he learned in Paris-spatial ambiguity. Prendergast’s best known paintings from this period are of Franklin Park and the South Shore near Boston. In these works, the genteel class are often portrayed in leisure activities, strolling through the park or relaxing by the water. They are commonly dressed in fine clothes, and are predominantly women and children. Prendergast’s figures lack definition; each shape is formed by masses of color, a characteristic that was certainly influenced by the Nabis. However, the lack of dark contour lines sets Prendergast apart from the modern French painters.

Further, although Prendergast painted out-of-doors, he was not a plein-air painter like the Impressionists. All of his pictures were adapted from sketches done on the spot, some themes were repeated while others were worked and reworked. As a result, most of his locations are easily identifiable. The artist’s later work was also typically spatially ambiguous, another trait adapted from his studies abroad. His images were not “flat,” but again lacked the clear definition of traditional perspective. One of Prendergast’s greatest talents was reconciling these themes and characteristics from contemporary art and unyieldingly adapting them to his own style.

Around 1898, financed by his patron Sarah Choate Sears, Prendergast traveled to Italy, spending about eighteen months abroad. He traveled extensively throughout Italy, including Venice, Padua, Siena, Florence, Naples, and Rome. In the spring of 1899, Prendergast sent finished watercolors to the annual Boston Water Color Club exhibition and then in a one person show at the Eastman Chase Gallery. The works were immediately sought by collectors and dealers and continue to this day to be the most treasured of his works. For example, "Splash of Sunshine and Rain" (1899, Collection of Alice M. Kaplan) is a magnificent depiction of St. Mark’s square in Venice. Prendergast captured the moment perhaps after a spring shower as the sun has emerged-the reflection of the cathedral in the water covering the square is a delightful illusion. Prendergast’s success in Boston quickly spread to New York. William Macbeth, an ambitious young dealer contacted Prendergast and arranged to be his dealer for the next decade, bringing the artist national recognition.

By 1900, New York had become the center of the American art world, and its extraordinary growth and social dynamism at the turn of the century made all other American cities pale in comparison. In March of 1900, a solo exhibition of Prendergast’s monotypes and watercolors was held at the Macbeth Gallery. The artist was immediately ranked among the important new artists of the city. He began to exhibit with urban realists Robert Henri, William Glackens, George Lukes, and John Sloan-who would later be referred to as the Ashcan School. He also became close friends with Arthur B. Davies.(4)

Prendergast began seeking similar sites in the United States that he had painted in Italy-tourist locales such as urban palaces, churches, and parks-places where he found large crowds spending leisure time. Central Park in New York City became a favorite spot. Opened in 1858, Central Park was first and foremost an equestrian park. Covering almost 900 acres, it’s miles of paved road were designed more for horse-power than for the casual stroll. When the carriage drives were completed in 1863, the majority of visitors were drawn there by horses. According to art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews, the presence of such a superior facility for carriages stimulated the private ownership of horses and rigs in New York, an expense that was far beyond the reach of the average citizen. Such excessive spending on carriages made Central Park the site of the most conspicuous display of wealth to be found in the city.(5) Prendergast often captured these displays in works such as "Central Park" (c. 1901, Whitney Museum of American Art).

As Prendergast’s career progressed, he continued to experiment with spatial ambiguity. His most constant compositional device was “banding,” or the horizontal stacking of formal units. For example, in the Museum’s "A Dock Scene" (c. 1900-05), Prendergast divides the action into three bands: the barges in the harbor in the foreground, the people milling about the dock in the middle, and the water and Boston cityscape in the background. “Trelllising” is another device he uses in which elements anchored in the lower bands of the composition extend to the upper bands as in "Summer’s Day (Summer, Summer Days)" (c. 1918-23, Whitney Museum of Art), in which trees extend from the first band into the second band in the background, thus connecting the composition. His third device was “climbing perspective” where figures were placed vertically, as if climbing a hill or seen from an elevation. This, coupled with spreading the figures over most of the surface achieved a tapestry-like effect, as in "Summer Outing on the Rocks (Nantasket)" (c. 1903-05, Private Collection).

Having recently escaped from site-specific scenes, Prendergast was profoundly influenced by art he had seen during a summer trip to Paris in 1907. He absorbed the radical styles of Cezanne, the Neo-Impressionists, and Matisse’s Fauves. Their anti-naturalist color and subject matter appealed to the American artist and he soon adapted them to his style. For example, "Bathers by the Sea" (c. 1910-13, Williams College Museum of Art) is his interpretation of the modern goddess and his first attempt to use the female nude in his work. In the painting, a group of nude women gather at the water’s edge. The composition is compressed, with land in the immediate foreground and water occupying most of the scene. The work is loosely rendered, giving the sense that elements are stacked on top of one another as opposed to receding naturally into the background.

In 1908, Prendergast exhibited with Robert Henri and the other urban artists in an exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries. The show became an event, traveling around the country, and earned the group the nickname of “The Eight.” According to Mathews, Henri’s philosophy of modern art was tied to the modernity of American life, specifically in New York. Prendergast shared these ideals, but with his next venture to Europe, his ideas began to change.

Prendergast’s acceptance into the New York art scene was due to the large amount of respect younger artists held for him. Having experimented in representing modern life for nearly twenty years, and his enthusiasm for spectacle made him like-minded in their eyes. By 1914, he found himself exhibiting alongside Dada artist’s Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Although he did not adapt the Dadaist notion of chance into his art, Prendergast respected his colleagues all the same. In 1917, both he and Charles exhibited in the famous Society of Independent Artists where Duchamp revealed his famous ready-made “sculpture,” "Fountain" (1917).(6)

Prendergast continued to paint until his death from prostate cancer in 1924. His later works were idyllic park and beach scenes, “echoing Renoir’s bathers and Puvis de Chavanne’s atmospheric historicism and ancient friezes (most commonly, Egyptian and ancient Greek). Mathews wrote of the artist, “Prendergast did not live to see an American society in which leisure became the hallmark of modern life as he had once imagined it would; instead he lived as the more typical American of the twentieth century-working until ill health or death brought a much needed respite.”(7)

1) Carol Clark, et al. Maurice Brazil Prendergast and Charles Prendergast: A Catalogue Raisonne, Munich: Prestel, 1990: 17.

2) Nancy Mowll Mathews, The Art of Leisure: Maurice Prendergast in the Williams College Museum of Art. Columbus: Excelsior Printing Co., 1999: 8. According to family records, Lucy Catherine died when she was around eighteen years old. Prendergast’s early life is sketchy.

3) Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachussetts, 1938, Retrospective Exhibition of the Work of Charles and Maurice Prendergast (exhibition catalogue with “Anecdotes of Maurice Prendergast” by Van Wyck Brookx): 33; quoted in Cecily Langdale, Monotypes by Maurice Prendergast in the Terra Musuem of American Art (Chicago: Terra Museum of American Art, 1984): 9.

4) All of the aforementioned artists are in the Museum’s collection.

5) Mathews, 29-31.

6) Duchamp’s "Fountain" was acquired from J. L. Mott Iron Word, a manufacturer for plumbing equipment. Before exhibiting the piece, the artist rotated the urinal ninety degrees from its normal, functional position, and left it unembellished except for the inscription “R. Mutt 1917”-a pseudonym that synthesized the name of the manufacturer and that of the popular comic strip “Mutt and Jeff.” The original Fountain has long since disappeared. In 1964, Duchamp entrusted the Galleries Schwartz in Milan with the production of a signed and numbered edition of his most important ready-mades. Each was fabricated to replicate the original and the edition for each was limited to eight. One can be found at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

7) Ibid, 47.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 5/17/04

Image credit: Gertrude Käsebier (American, 1852–1934), Maurice Prendergast, 1913, photographic print, Macbeth Gallery records, 1947–1948, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., Photograph courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution