Rudy Burckhardt

American, born Switzerland

(Basel, Switzerland, 1914 - 1999, Searsmont, Maine)

Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel, Switzerland in 1914 to a prominent and well-regarded family. His mother, Esther Iselin was a member of an influential banking family and his father, Rudolph Burckhardt, owned a successful silk ribbon business.(1) Burckhardt also had several other relatives of note; his grandfather, Isaac Iselin, a General and the chief of the Basel Army in 1912 went on to become a respected judge and government official and the well-known historian and Renaissance art specialist Jacob Burckhardt was also a distant relative. Burckhardt's immediate family included two older sisters, a younger sister and a younger brother.

Growing up in a privileged environment in Basel, which at the time was somewhat provincial, created a longing in Burckhardt to explore larger, more exciting cities. His education was classical in nature, with an emphasis on Latin and Greek languages and in 1933, at the age of nineteen, Burckhardt moved to Geneva to study medicine. However, he often did not attend classes and eventually dropped out of school. Instead, Burckhardt began expanding on his explorations of photography that began at the age of fifteen when he made a pinhole camera. Following his brief medical studies Burckhardt traveled to London and Paris, two cities that dazzled him, and began capturing street life with his camera.

Upon his return to Basel in 1934, Burckhardt met dancer, poet and critic Edwin Denby, a man who made an instantaneous impact on the young photographer and soon became his romantic partner. Burckhardt states, "And then I met Edwin and that was just at the right time. I had studied pre-med for a year in Geneva, I had been in London and Paris. I was back home, dropping out of medical school, I didn't know what I was going to do. I was just moping around. And Edwin was like a vision of the big world, cosmopolitan and...."(2) Once Burckhardt turned twenty-one he was ready for a change and decided to follow Denby to New York. Facilitating this move, in August 1935, was his recent inheritance of $20,000 from his father’s estate.(3)

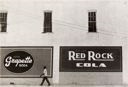

On his arrival in New York, Burckhardt moved with Denby into a loft space on West 21st Street in the Chelsea neighborhood where rent was $18 a month. Burckhardt describes his early days as somewhat carefree, " I came here in the Depression in 1935 and I was very lucky. I had some money from Switzerland that I had inherited so I had a very nice time. I didn't need to get a job. I could just play around and do what I felt like. Other people were sleeping in the doorways and on newspapers and things."(4) Denby knew many artists, dancers, musicians and poets who he introduced to Burckhardt, and Burckhardt, with his unassuming personality, fit easily into the thriving artistic community that would later be known as the New York School.(5) One of the friendships began by accident; Denby and Burckhardt met Abstract Expressionist painter, Willem de Kooning—at that time an unknown struggling artist—who lived in the adjacent building. One evening de Kooning's cat wandered over to their fire escape and they took it in. The reuniting of cat and owner provided an introduction that led to a fast friendship. In fact, Denby and Burckhardt became early patrons of the painter, helping to support the artist when he needed money and purchasing paintings on occasion. De Kooning, in appreciation and friendship, also gifted to Burckhardt and Denby several works.(6) Although excited by New York and comfortable in his social setting the city still intimidated Burckhardt artistically, he recalls, "Well, to take pictures in New York, it took me about two or three years before I was ready, because it was so overwhelming at first."(7) He elaborates, "I was quite overwhelmed with its grandeur and ceaseless energy.... The tremendous difference in scale between the soaring buildings and people in the street astonished me."(8) As such, it took awhile before Burckhardt even attempted to include both people and buildings in the same frame; his early works focused on the feet and lower bodies of pedestrians as a way to avoid dealing with changes in scale. In 1937 Burckhardt purchased his first film camera, a secondhand 16-millimeter "Victor" camera with a one-inch lens. He began a lifelong self-taught study into film and, in the beginning, his short films related closely to his photographs, sharing the same subject: people in the streets. Burckhardt's photographic street scenes are not limited to large cities. A love of travel propelled Burckhardt and he believed that his camera was his ticket to explore the world. Thus, in 1937 Burckhardt and Denby set out for Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The two spent about a month together but after Denby returned to New York Burckhardt stayed on for another eight months with a local woman named Germaine. It appears that at this time Burckhardt's and Denby's romantic relationship ended but their close friendship continued to endure.(9) A few years after his return to New York in 1941, around the time that his inheritance money was about to run out, Burckhardt received a draft notice from the United States Army. This was not Burckhardt's first foray into the military; he spent time in a medical unit in the Swiss army when he was younger. However, while he never saw combat, Burckhardt found military life very disagreeable. After receiving basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, he went to Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where he spent two years in the Caribbean as a signal corps photographer. While in Trinidad Burckhardt tried to make the best of the situation by investigating the culture and taking many personal photographs capturing Caribbean life. While serving in the army, Burckhardt finally received his American citizenship.(10) Yet Burckhardt hated army life. After three years of actively trying to leave the army he received a discharge for a nervous disability. Burckhardt accomplished this by first calling in sick everyday, complaining of headaches, insomnia, and depression; he also stopped eating and said he was gay. These efforts were to no avail, but prior to shipping off to Europe in 1944 the army sent Burckhardt to a hospital for observation. Denied discharge, Burckhardt resumed limited, stateside duty. Almost immediately, however, Burckhardt returned to a hospital where he underwent further observation. At this point, a study of his case history revealed that Burckhardt suffered from various ailments including psychoneurosis, persecution mania, suicidal tendencies, severe depression, and, after three months the army finally released him from his duty.(11) Returning to civilian life Burckhardt continued with his photography, first during a trip to Mexico and then back in New York where he focused on several still-life compositions and began a series of black and white photographs(12) of New York buildings—images that are now his most iconic. Using a small handheld Leica 35mm camera Burckhardt focused primarily on streets and buildings located in midtown and downtown New York, never venturing above Forty-second Street. During this period he married German painter Edith Schloss in 1947 and had a son Jacob, in 1949. In addition to his photographic work Burckhardt took advantage of the GI Bill to undertake a new field of study. Feeling like there was nothing new to learn regarding photography and since, at the time, there were no film programs, he chose painting. Several of his friends were under the instruction of Hans Hoffman but Burckhardt desired someone different and worked with the French cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966)(13). While Ozenfant proved inspirational, not only did the two artists’ styles differ as Burckhardt painted in a primitive realist manner, but their approach did as well—Ozenfant was very disciplined, Burckhardt much more relaxed—and after a year Burckhardt decided to leave Ozenfant's tutelage. He continued painting, even taking de Kooning up on the offer of a painting lesson—a one-lesson attempt that did not work out. Instead, he furthered his studies by attending the Academy of Naples, in Italy while the GI Bill was still in effect. Traveling to Italy for school was one of many trips abroad Burckhardt took after the war. While traveling to such places as Italy, France, Greece, Morocco, and, later, Peru, Burckhardt continued to take pictures of daily street life but these images are subtly different from his New York photographs. Phillip Lopate states, "The pictures Rudy took on his European trips of 1947 and 1951 have a different quality from his New York street scenes: they seem more in keeping with the narrative-vignette style of the great Parisian humanist photographers, [Henri] Cartier-Bresson [1908 - 2004], [Robert] Doisneau [1912 - 1994], Brassaï [1899 - 1994], and [Édouard] Boubat [1923 - 1999]. Burckhardt admired their work, particularly Cartier-Bresson' s."(14) Other photographers were not the only artists who influenced Burckhardt's work. Burckhardt was particularly drawn to Dutch painter Piet Mondrian's (1872 - 1944) aesthetic and incorporated a similar sensibility of minimal and rectilinear compositions into his street images—a technique that Lopate argues Burckhardt was one of the earliest pioneers of in this genre.(15) In between trips to Europe, Africa and the American South, Burckhardt began receiving recognition for his images and enjoyed his first exhibition of photographs in 1948 at the Photo League Gallery in New York. While recognized in some circles Burckhardt, in many ways, never fully enjoyed the critical success of many of his peers, primarily as a result of his own reticence to participate fully in the art market. New York Times art critic Holland Carter discusses this aspect of Burckhardt's personality as such, "Burckhardt never made the leap to that world. Incapable of self-promotion, allergic to aristocracies of power, he kept to the bohemia he knew, where art making was, ideally, part of a pattern of democratic sociability; a shared aspiration, not a competitive business."(16) Furthering this, Burckhardt's own technique played against the images of highly regarded artists Weegee (Arthur Felig, American, 1899-1968), Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) and Berenice Abbott (American 1898-1991) who each portrayed a darker version of the city or contained a social consciousness-based agenda within their imagery. In contrast, Burckhardt's images embody a playful, light quality both in imagery and in the quality of the print. Burckhardt's photographs are less dramatic than other photographers’ yet they portray the reality of the everyday with a view that rings true.

Poet and art critic John Ashbery (American, born 1928) once stated that his good friend Burckhardt "has remained unsung for so long that he is practically a subterranean monument."(17) Yet, many of Burckhardt's peers held his ability in high esteem. Viewed as a photographer with a sensitive eye who revealed his subjects with freshness atypical of the era, Burckhardt was sought out by ARTnews Magazine editor Thomas B. Hess to create portraits of artists working, along with their artworks, for a series of articles titled {Artist Name] Paints a Picture. Beginning in 1950 and continuing until 1964 Burckhardt photographed various artists in their studios including Willem de Kooning, Hans Hoffman, Alex Katz, Marisol, Joan Mitchell, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, and many others, becoming one of the first photographers of the New York School. Burckhardt felt he was successful in producing these types of images because, "I was good at angles, lighting, sometimes the drama of sculpture photography, but never glamour, which was O.K. because glamour then was reserved for fashion magazines and advertising."(18) While that might be part of why these portraits work, another aspect is the intimacy that Burckhardt captures and the air of familiarity he brings to the image. Curator Robert Storr suggests that this is because Burckhardt knew and was friends with all the players of the modern art movement; since Burckhardt was part of this artist's circle his subjects felt comfortable to be themselves.(19) Often they forgot his purpose for being in the studio with them—Burckhardt easily fit into their personal space while preserving a sense of objectivity, a quality that shines through in his photographs providing intimate glimpses of these artists and their process. In addition to his work for the magazine Burckhardt also was the photographer of choice for several galleries including Leo Castelli, Betty Parsons Gallery and Sidney Janis Gallery, and for a few New York museums. The fact that Burckhardt could work with fellow artists and enjoy a sense of community was important to him. As such, he often collaborated with other artists in his film work. Between 1936 and 1997 Burckhardt created ninety-five films, a number of them collaborations with other artists of various disciplines including John Ashbery, Joseph Cornell, Edwin Denby, Jane Freilicher, Red Grooms, Alex Katz, Kenneth Koch, Taylor Mead, Ron Padgett, Charles Simmonds, Larry Rivers, Neil Welliver and others.(20) Throughout his career, Burckhardt often alternated between still photographs and movies yet he felt he was best at filmmaking. He says of photography that it is "slightly unsatisfactory, because it's too quick, too instantaneous."(21) In fact, Burckhardt took an almost decade long break from photography in the 1980s, yet he never ceased making movies.(22) Certainly, Burckhardt's love of the moving image bled over into his photography. His still images have a cinematic quality and exude a sense that they are part of a larger narrative. Finding comfort in his community of friends, in 1956 Burckhardt began spending summers in Maine, in an area where many artists had second homes. Burckhardt and Schloss purchased a place in Deer Isle, Maine. All was not idyllic however; Burckhardt's marriage had issues and he separated from Schloss in 1961. In 1964, the year he turned fifty, his divorce became final. That same year he married painter Yvonne Jacquette and his son Thomas was born. Prior to these changes in 1963 Burckhardt, Jacquette and Edwin Denby purchased a new home in Maine, this one in the town of Searsmont near a place owned by painter Alex Katz and his family. All the while Burckhardt continued photographing city scenes but he also turned to nature photography, images of nudes, and collage works along with resuming a more regular painting practice. In 1967, Neil Welliver, head of the art department at the University of Pennsylvania engaged Burckhardt to teach film (and later, painting). Burckhardt taught for seventeen years, until 1984. As Burckhardt reached his 80s in the early 1990s he suffered from hearing loss. His initial resistance to using a hearing aid isolated the artist but he finally succumbed to one, which helped for a while. Yet, as his health declined further Burckhardt chose to end his life. He committed suicide by drowning in the pond near his home in Searsmont, Maine at the age of 85 on August 1, 1999, the same place that his dear friend Edwin Denby also chose to end his life.

(1) Primary sources for this essay come from the following: "Rudy Burckhardt, Mobile Homes," Z Press, Vermont, 1979; Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," Zoland Books, Inc., Cambridge, MA, 1994; "Mobile Homes," Vermont, 1979; "Rudy Burckhardt," IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, Valencia, Spain, 1998; Oral history interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 Jan. 14, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; and Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 2004, p.23-24. (2) Rudy Burckhardt in "Rudy Burckhardt" and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 70. (3) Burckhardt's father died when the artist was fourteen. (4) Rudy Burckhardt in Oral history interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 Jan. 14, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. (5) The New York School was an informal group of artists working in a variety of media—painting, poetry, dance and music—who came to prominence during the 1950s and 1960s. Their work has a basis in Surrealism and the avant-garde and they were the pioneers of action painting, abstract expressionism, and experimental music and theater. Among others, at the core of the group were artists Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollack, poets John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, Kenneth Koch, and Ron Padgett, dancers Edwin Denby and Yvonne Rainer, and musicians John Cage, Kurt Weil, and Lotte Lenya.

(6) The later sales of some of these de Kooning works helped to finance the purchase of a home in Maine, Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 33. (7) Rudy Burckhardt in Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 20. (8) Rudy Burckhardt quoted in Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 33. (9) Philip Lopate suggests that it is at this point that Burckhardt's and Denby's relationship shifted in "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 18.

(10) The timeline between when Burckhardt received his draft notice to his receiving his citizenship is not fully clear, but it does appear that, indeed, he was drafted prior to becoming a citizen. See biographical notes in "Rudy Burckhardt," IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, p.196.

(11) Burckhardt briefly discusses his attempts to leave the army in Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," pps. 88-94, and in more detail in "Mobile Homes." In both accounts Burckhardt adopts a joking manner about getting out but Phillip Lopate in "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 19 suggests that Burckhardt's depression during that period was very real and that he struggled with melancholy on and off his entire adult life. (12) In fact, Burckhardt shot almost exclusively in black and white. The only time he ventured into color was while traveling in Bali in 1995. (13) Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 138. (14) Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p.23-24. (15) Ibid. p. 12. (16) Holland Cotter, "Art Review: 'Subterranean Monuments’: Up From the Underground," "New York Times," August 11, 2006. (17) John Ashbery quoted in Philip Lopate, p. 7. (18) Rudy Burckhardt quoted in Philip Lopate p. 31.

(19) Robert Storr, "Rudy Burckhardt", IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, p.18 (20) The Museum of Modern Art in New York honored his accomplishments in with a retrospective in 1987. (21) Rudy Burckhard in "Talking Pictures," p. 18. (22) Philip Lopate, p. 26.

J. Jankauskas 2.2012

American, born Switzerland

(Basel, Switzerland, 1914 - 1999, Searsmont, Maine)

Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel, Switzerland in 1914 to a prominent and well-regarded family. His mother, Esther Iselin was a member of an influential banking family and his father, Rudolph Burckhardt, owned a successful silk ribbon business.(1) Burckhardt also had several other relatives of note; his grandfather, Isaac Iselin, a General and the chief of the Basel Army in 1912 went on to become a respected judge and government official and the well-known historian and Renaissance art specialist Jacob Burckhardt was also a distant relative. Burckhardt's immediate family included two older sisters, a younger sister and a younger brother.

Growing up in a privileged environment in Basel, which at the time was somewhat provincial, created a longing in Burckhardt to explore larger, more exciting cities. His education was classical in nature, with an emphasis on Latin and Greek languages and in 1933, at the age of nineteen, Burckhardt moved to Geneva to study medicine. However, he often did not attend classes and eventually dropped out of school. Instead, Burckhardt began expanding on his explorations of photography that began at the age of fifteen when he made a pinhole camera. Following his brief medical studies Burckhardt traveled to London and Paris, two cities that dazzled him, and began capturing street life with his camera.

Upon his return to Basel in 1934, Burckhardt met dancer, poet and critic Edwin Denby, a man who made an instantaneous impact on the young photographer and soon became his romantic partner. Burckhardt states, "And then I met Edwin and that was just at the right time. I had studied pre-med for a year in Geneva, I had been in London and Paris. I was back home, dropping out of medical school, I didn't know what I was going to do. I was just moping around. And Edwin was like a vision of the big world, cosmopolitan and...."(2) Once Burckhardt turned twenty-one he was ready for a change and decided to follow Denby to New York. Facilitating this move, in August 1935, was his recent inheritance of $20,000 from his father’s estate.(3)

On his arrival in New York, Burckhardt moved with Denby into a loft space on West 21st Street in the Chelsea neighborhood where rent was $18 a month. Burckhardt describes his early days as somewhat carefree, " I came here in the Depression in 1935 and I was very lucky. I had some money from Switzerland that I had inherited so I had a very nice time. I didn't need to get a job. I could just play around and do what I felt like. Other people were sleeping in the doorways and on newspapers and things."(4) Denby knew many artists, dancers, musicians and poets who he introduced to Burckhardt, and Burckhardt, with his unassuming personality, fit easily into the thriving artistic community that would later be known as the New York School.(5) One of the friendships began by accident; Denby and Burckhardt met Abstract Expressionist painter, Willem de Kooning—at that time an unknown struggling artist—who lived in the adjacent building. One evening de Kooning's cat wandered over to their fire escape and they took it in. The reuniting of cat and owner provided an introduction that led to a fast friendship. In fact, Denby and Burckhardt became early patrons of the painter, helping to support the artist when he needed money and purchasing paintings on occasion. De Kooning, in appreciation and friendship, also gifted to Burckhardt and Denby several works.(6) Although excited by New York and comfortable in his social setting the city still intimidated Burckhardt artistically, he recalls, "Well, to take pictures in New York, it took me about two or three years before I was ready, because it was so overwhelming at first."(7) He elaborates, "I was quite overwhelmed with its grandeur and ceaseless energy.... The tremendous difference in scale between the soaring buildings and people in the street astonished me."(8) As such, it took awhile before Burckhardt even attempted to include both people and buildings in the same frame; his early works focused on the feet and lower bodies of pedestrians as a way to avoid dealing with changes in scale. In 1937 Burckhardt purchased his first film camera, a secondhand 16-millimeter "Victor" camera with a one-inch lens. He began a lifelong self-taught study into film and, in the beginning, his short films related closely to his photographs, sharing the same subject: people in the streets. Burckhardt's photographic street scenes are not limited to large cities. A love of travel propelled Burckhardt and he believed that his camera was his ticket to explore the world. Thus, in 1937 Burckhardt and Denby set out for Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The two spent about a month together but after Denby returned to New York Burckhardt stayed on for another eight months with a local woman named Germaine. It appears that at this time Burckhardt's and Denby's romantic relationship ended but their close friendship continued to endure.(9) A few years after his return to New York in 1941, around the time that his inheritance money was about to run out, Burckhardt received a draft notice from the United States Army. This was not Burckhardt's first foray into the military; he spent time in a medical unit in the Swiss army when he was younger. However, while he never saw combat, Burckhardt found military life very disagreeable. After receiving basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia, he went to Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where he spent two years in the Caribbean as a signal corps photographer. While in Trinidad Burckhardt tried to make the best of the situation by investigating the culture and taking many personal photographs capturing Caribbean life. While serving in the army, Burckhardt finally received his American citizenship.(10) Yet Burckhardt hated army life. After three years of actively trying to leave the army he received a discharge for a nervous disability. Burckhardt accomplished this by first calling in sick everyday, complaining of headaches, insomnia, and depression; he also stopped eating and said he was gay. These efforts were to no avail, but prior to shipping off to Europe in 1944 the army sent Burckhardt to a hospital for observation. Denied discharge, Burckhardt resumed limited, stateside duty. Almost immediately, however, Burckhardt returned to a hospital where he underwent further observation. At this point, a study of his case history revealed that Burckhardt suffered from various ailments including psychoneurosis, persecution mania, suicidal tendencies, severe depression, and, after three months the army finally released him from his duty.(11) Returning to civilian life Burckhardt continued with his photography, first during a trip to Mexico and then back in New York where he focused on several still-life compositions and began a series of black and white photographs(12) of New York buildings—images that are now his most iconic. Using a small handheld Leica 35mm camera Burckhardt focused primarily on streets and buildings located in midtown and downtown New York, never venturing above Forty-second Street. During this period he married German painter Edith Schloss in 1947 and had a son Jacob, in 1949. In addition to his photographic work Burckhardt took advantage of the GI Bill to undertake a new field of study. Feeling like there was nothing new to learn regarding photography and since, at the time, there were no film programs, he chose painting. Several of his friends were under the instruction of Hans Hoffman but Burckhardt desired someone different and worked with the French cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966)(13). While Ozenfant proved inspirational, not only did the two artists’ styles differ as Burckhardt painted in a primitive realist manner, but their approach did as well—Ozenfant was very disciplined, Burckhardt much more relaxed—and after a year Burckhardt decided to leave Ozenfant's tutelage. He continued painting, even taking de Kooning up on the offer of a painting lesson—a one-lesson attempt that did not work out. Instead, he furthered his studies by attending the Academy of Naples, in Italy while the GI Bill was still in effect. Traveling to Italy for school was one of many trips abroad Burckhardt took after the war. While traveling to such places as Italy, France, Greece, Morocco, and, later, Peru, Burckhardt continued to take pictures of daily street life but these images are subtly different from his New York photographs. Phillip Lopate states, "The pictures Rudy took on his European trips of 1947 and 1951 have a different quality from his New York street scenes: they seem more in keeping with the narrative-vignette style of the great Parisian humanist photographers, [Henri] Cartier-Bresson [1908 - 2004], [Robert] Doisneau [1912 - 1994], Brassaï [1899 - 1994], and [Édouard] Boubat [1923 - 1999]. Burckhardt admired their work, particularly Cartier-Bresson' s."(14) Other photographers were not the only artists who influenced Burckhardt's work. Burckhardt was particularly drawn to Dutch painter Piet Mondrian's (1872 - 1944) aesthetic and incorporated a similar sensibility of minimal and rectilinear compositions into his street images—a technique that Lopate argues Burckhardt was one of the earliest pioneers of in this genre.(15) In between trips to Europe, Africa and the American South, Burckhardt began receiving recognition for his images and enjoyed his first exhibition of photographs in 1948 at the Photo League Gallery in New York. While recognized in some circles Burckhardt, in many ways, never fully enjoyed the critical success of many of his peers, primarily as a result of his own reticence to participate fully in the art market. New York Times art critic Holland Carter discusses this aspect of Burckhardt's personality as such, "Burckhardt never made the leap to that world. Incapable of self-promotion, allergic to aristocracies of power, he kept to the bohemia he knew, where art making was, ideally, part of a pattern of democratic sociability; a shared aspiration, not a competitive business."(16) Furthering this, Burckhardt's own technique played against the images of highly regarded artists Weegee (Arthur Felig, American, 1899-1968), Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) and Berenice Abbott (American 1898-1991) who each portrayed a darker version of the city or contained a social consciousness-based agenda within their imagery. In contrast, Burckhardt's images embody a playful, light quality both in imagery and in the quality of the print. Burckhardt's photographs are less dramatic than other photographers’ yet they portray the reality of the everyday with a view that rings true.

Poet and art critic John Ashbery (American, born 1928) once stated that his good friend Burckhardt "has remained unsung for so long that he is practically a subterranean monument."(17) Yet, many of Burckhardt's peers held his ability in high esteem. Viewed as a photographer with a sensitive eye who revealed his subjects with freshness atypical of the era, Burckhardt was sought out by ARTnews Magazine editor Thomas B. Hess to create portraits of artists working, along with their artworks, for a series of articles titled {Artist Name] Paints a Picture. Beginning in 1950 and continuing until 1964 Burckhardt photographed various artists in their studios including Willem de Kooning, Hans Hoffman, Alex Katz, Marisol, Joan Mitchell, Jackson Pollack, Mark Rothko, and many others, becoming one of the first photographers of the New York School. Burckhardt felt he was successful in producing these types of images because, "I was good at angles, lighting, sometimes the drama of sculpture photography, but never glamour, which was O.K. because glamour then was reserved for fashion magazines and advertising."(18) While that might be part of why these portraits work, another aspect is the intimacy that Burckhardt captures and the air of familiarity he brings to the image. Curator Robert Storr suggests that this is because Burckhardt knew and was friends with all the players of the modern art movement; since Burckhardt was part of this artist's circle his subjects felt comfortable to be themselves.(19) Often they forgot his purpose for being in the studio with them—Burckhardt easily fit into their personal space while preserving a sense of objectivity, a quality that shines through in his photographs providing intimate glimpses of these artists and their process. In addition to his work for the magazine Burckhardt also was the photographer of choice for several galleries including Leo Castelli, Betty Parsons Gallery and Sidney Janis Gallery, and for a few New York museums. The fact that Burckhardt could work with fellow artists and enjoy a sense of community was important to him. As such, he often collaborated with other artists in his film work. Between 1936 and 1997 Burckhardt created ninety-five films, a number of them collaborations with other artists of various disciplines including John Ashbery, Joseph Cornell, Edwin Denby, Jane Freilicher, Red Grooms, Alex Katz, Kenneth Koch, Taylor Mead, Ron Padgett, Charles Simmonds, Larry Rivers, Neil Welliver and others.(20) Throughout his career, Burckhardt often alternated between still photographs and movies yet he felt he was best at filmmaking. He says of photography that it is "slightly unsatisfactory, because it's too quick, too instantaneous."(21) In fact, Burckhardt took an almost decade long break from photography in the 1980s, yet he never ceased making movies.(22) Certainly, Burckhardt's love of the moving image bled over into his photography. His still images have a cinematic quality and exude a sense that they are part of a larger narrative. Finding comfort in his community of friends, in 1956 Burckhardt began spending summers in Maine, in an area where many artists had second homes. Burckhardt and Schloss purchased a place in Deer Isle, Maine. All was not idyllic however; Burckhardt's marriage had issues and he separated from Schloss in 1961. In 1964, the year he turned fifty, his divorce became final. That same year he married painter Yvonne Jacquette and his son Thomas was born. Prior to these changes in 1963 Burckhardt, Jacquette and Edwin Denby purchased a new home in Maine, this one in the town of Searsmont near a place owned by painter Alex Katz and his family. All the while Burckhardt continued photographing city scenes but he also turned to nature photography, images of nudes, and collage works along with resuming a more regular painting practice. In 1967, Neil Welliver, head of the art department at the University of Pennsylvania engaged Burckhardt to teach film (and later, painting). Burckhardt taught for seventeen years, until 1984. As Burckhardt reached his 80s in the early 1990s he suffered from hearing loss. His initial resistance to using a hearing aid isolated the artist but he finally succumbed to one, which helped for a while. Yet, as his health declined further Burckhardt chose to end his life. He committed suicide by drowning in the pond near his home in Searsmont, Maine at the age of 85 on August 1, 1999, the same place that his dear friend Edwin Denby also chose to end his life.

(1) Primary sources for this essay come from the following: "Rudy Burckhardt, Mobile Homes," Z Press, Vermont, 1979; Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," Zoland Books, Inc., Cambridge, MA, 1994; "Mobile Homes," Vermont, 1979; "Rudy Burckhardt," IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, Valencia, Spain, 1998; Oral history interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 Jan. 14, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; and Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 2004, p.23-24. (2) Rudy Burckhardt in "Rudy Burckhardt" and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 70. (3) Burckhardt's father died when the artist was fourteen. (4) Rudy Burckhardt in Oral history interview with Rudy Burckhardt, 1993 Jan. 14, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. (5) The New York School was an informal group of artists working in a variety of media—painting, poetry, dance and music—who came to prominence during the 1950s and 1960s. Their work has a basis in Surrealism and the avant-garde and they were the pioneers of action painting, abstract expressionism, and experimental music and theater. Among others, at the core of the group were artists Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollack, poets John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, Kenneth Koch, and Ron Padgett, dancers Edwin Denby and Yvonne Rainer, and musicians John Cage, Kurt Weil, and Lotte Lenya.

(6) The later sales of some of these de Kooning works helped to finance the purchase of a home in Maine, Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 33. (7) Rudy Burckhardt in Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 20. (8) Rudy Burckhardt quoted in Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 33. (9) Philip Lopate suggests that it is at this point that Burckhardt's and Denby's relationship shifted in "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 18.

(10) The timeline between when Burckhardt received his draft notice to his receiving his citizenship is not fully clear, but it does appear that, indeed, he was drafted prior to becoming a citizen. See biographical notes in "Rudy Burckhardt," IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, p.196.

(11) Burckhardt briefly discusses his attempts to leave the army in Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," pps. 88-94, and in more detail in "Mobile Homes." In both accounts Burckhardt adopts a joking manner about getting out but Phillip Lopate in "Rudy Burckhardt," p. 19 suggests that Burckhardt's depression during that period was very real and that he struggled with melancholy on and off his entire adult life. (12) In fact, Burckhardt shot almost exclusively in black and white. The only time he ventured into color was while traveling in Bali in 1995. (13) Rudy Burckhardt and Simon Pettet, "Talking Pictures," p. 138. (14) Philip Lopate, "Rudy Burckhardt," p.23-24. (15) Ibid. p. 12. (16) Holland Cotter, "Art Review: 'Subterranean Monuments’: Up From the Underground," "New York Times," August 11, 2006. (17) John Ashbery quoted in Philip Lopate, p. 7. (18) Rudy Burckhardt quoted in Philip Lopate p. 31.

(19) Robert Storr, "Rudy Burckhardt", IVAM Centre Julio Gonazáles, p.18 (20) The Museum of Modern Art in New York honored his accomplishments in with a retrospective in 1987. (21) Rudy Burckhard in "Talking Pictures," p. 18. (22) Philip Lopate, p. 26.

J. Jankauskas 2.2012

Artist Objects