Alexander Archipenko

American, born Ukraine

(Kiev, Ukraine, 1887 - 1964, New York, New York)

Born on May 30, 1887 in Kiev, Ukraine, Alexander Archipenko (Aleksandr Porfirevich Arkhipenko) had an early exposure to art. (1) He often witnessed his grandfather painting icons for the Orthodox Church (2) and, as a young boy, Archipenko encountered a work that would make a great impression on him, an early idol sculpture in the gardens of the University of Kiev where his father worked.(3) These early experiences made an impact and influenced his thinking about art in adulthood. Another memory from his childhood demonstrates how he developed critical thinking in regard to how objects occupy space. He recalls his parents bringing home two identical vases and,

"that as he looked at them, he was seized by the urge to place them close to each other. No sooner had he done this, he discovered a third, immaterial vase formed by the space between the first two." (4)

This discovery was important for Archipenko and would later influence his work greatly. However, prior to developing his innovative sculptural ideas, Archipenko needed to learn more about art. Growing up in an affluent family, Archipenko had many opportunities available to him. (5) Yet, his choice to pursue art caused a strain in his relationship with his father, who had hoped that Archipenko would follow in his footsteps as an engineer and inventor. Instead, during his teenage years from 1902–1905, Archipenko studied painting and sculpture at the School of Art in Kiev. The conservative atmosphere of his class, however, aggravated his sensibilities, and he protested the system along with some of his classmates, leading to his expulsion. The following year, in 1906, Archipenko struck out on his own and moved to Moscow. It was here that he began to have some success with his art, participating in several group exhibitions and showing his reductive figurative works that often had missing body parts or that focused on partial forms.

In 1908, at the age of 21, Archipenko left Russia for good, moving to Paris, France. In Paris, Archipenko's education continued on an informal basis. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but dropped out after two weeks. Instead, he immersed himself in the city's rich museum and artistic community where his ideas really began to expand. Spending time at the Louvre, taking in Byzantine, Gothic, and archaic art along with examples of primitive and folk artists, influenced Archipenko immensely. Additionally, Archipenko simultaneously began frequenting cafes and artists' colonies including La Ruche, becoming close friends with many of the artists, critics, and poets at the forefront of artistic thinking that brought forward Cubism. The spirit of intellectual and artistic exchange energized Archipenko and his associations with artists such as Fernand Léger (French, 1881–1955), Robert Delaunay (French, 1885–1941), Henri Le Fauconnier (French, 1881–1946), Albert Gleizes (French 1881–1953), and Jean Metzinger (French, 1883–1956) helped foster his career. In 1910, Archipenko exhibited alongside cubist painters at the Salon des Indépendants. This exhibition was not only one of the first exhibitions to feature cubist works but it also served as Archipenko's first exhibition in Paris. He included five sculptures and one painting, and while never fully embracing Cubism, Archipenko did incorporate several cubist elements within his works. For example, he reduced body parts into essential angular elements along with referencing archaic and primitive works.

After his inclusion within the Salon des Indépendants, Archipenko entered a period of intense productivity and an evolution in style spurred on by the support and promotion of friends and critics Guillaume Apollinaire (French 1880–1918) and Blaise Cendrars (Swiss, 1887–1961). In 1911, Archipenko became part of a Cubist group that included the Duchamp brothers (Jacques Villon, [French, 1875–1963] Raymond Duchamp Villon [French, 1876–1918] and Marcel Duchamp [French, 1887–1968]) along with other friends including Gleizes, Leger, Le Fauconnier, Metzinger, and Francis Picabia (French, 1879–1953). He often exhibited alongside these artists, showing in the Salon d'Automne from 1911 to 1913. During this period, in 1912, Archipenko opened his first art school, a pursuit that he followed at multiple times in many locales, teaching extensively throughout his life.

Archipenko's style during this period developed from his rejection of Auguste Rodin's (French, 1840–1917) sculptural techniques. Although Rodin's expressionistic works were well regarded at the time, Archipenko stated, "I hated Rodin, who was then fashionable. His sculptures reminded me of chewed bread that one spits on a base, or the crooked corpses from Pompeii." (6) Instead, inspired by the Cubists and Italian Futurists, Archipenko forged new ground with his sculptures by incorporating collage and using nontraditional materials such as a combination of bronze, found objects, glass, mirrors, plastic, and sheet metal. By 1912, he fully embraced the combination of these different materials and began working in the interstices of two- and three-dimensions. The years 1913–1914 were pivotal for Archipenko. In 1913, four plaster sculptural works along with five works on paper by him were included in the seminal International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York, otherwise known as the Armory Show, which also traveled to Boston and Chicago. This exhibition shocked and scandalized many Americans who were comfortable and familiar with realistic art, rather then the modern works on view. Though controversial at the time, the exhibition enjoys a lasting legacy, and it influenced many American artists while creating a new audience for modern art in the U.S. Additionally, some of the works of art, including Archipenko's, found homes with American collectors interested in the new progressive styles of European artists. While Archipenko's sculptures failed to find buyers, artist and dealer Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946) purchased all five drawings and continued to support Archipenko's work over the course of many years.

Additionally in 1913, Archipenko embraced another art form, that of printmaking. He worked in a variety of printmaking techniques including lithography, drypoint, silk-screen, embossing, and etching. His first print was a lithograph entitled Abstraction (Seated Figure), featuring abstracted forms rendered in a futuristic style. This print later served as an inspiration for the 1959 sculpture, Abstraction. This is often how Archipenko worked, returning to earlier ideas and creating a symbiotic relationship between his drawings, prints, and sculptural works. As he explored his ideas in one medium it would spur ideas for exploration in another format. Remarking on the relationship between the works on paper and the sculptures, Archipenko scholar Donald Karshan states, "Archipenko's works on paper were either studies for or analysis and refinement after his three-dimensional investigations." (7) Curator Deborah A. Goldberg continues, "With its great spontaneity and diversity, printmaking gave Archipenko a further outlet for expression. He learned to manipulate the unique effects of this medium to produce what could not be achieved in a drawing alone." (8) While Archipenko enjoyed working both sculpturally and on paper, his printmaking output is small in comparison to his prolific three-dimensional legacy. Creating prints sporadically throughout his career, Archipenko only produced a total of 54 prints from 1913 until 1963. (9)

Also during 1913 and 1914, Archipenko also made many of his most important sculptures including Carosel Pierrot (1913), Medrano II (1913), and Boxing (1914). At the spring 1914 Salon des Indépendants exhibition, Archipenko showed these works alongside Gondolier (1914). Singled out by Apollinaire, these works caused a stir in society for Archipenko's inventive use of materials. (10) Despite the controversy, three of the works found a buyer, the Italian painter, Alberto Magnelli (1888–1971). (11)

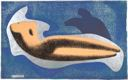

Late in 1914, due to the encroachment of World War I on Paris, Archipenko left for Nice, in the south of France. At this time, he began heavily experimenting with what he termed "sculpto-paintings," a fusion of both painting and sculpture. These works, polychrome bronzes that brought sculptural relief elements to the two-dimensional plane, became not only a signature style for Archipenko but also a significant contribution to modern sculpture. The sculpto-paintings varied in format; some consist of assemblage while others are painted reliefs in plaster or papier-mâché. Creating almost forty scupto-paintings during the war years, Archipenko returned to this process again in the 1950s. Additionally, going back to his early memory of the two vases from his childhood, Archipenko began incorporating voids into his works as a "'symbol' for an absent volume." (12) By playing with mass and void, the convex and the concave, and light and shadows, Archipenko fully exploited the shape and form of the absent material as much as what was present. This invention of the void in sculpture became one of his seminal achievements in modern art and is seen in many works over a period of several years beginning in 1914 including Seated Woman, 1920. Art historian Katherine Michaelson, calls Archipenko a "pioneer of modern sculpture," and succinctly summarizes his contributions to modern art:

"He initiated the opening-up of sculpture, not just by piercing a hole into it, but by presenting an alternative to the traditional notion of the monolith that merely displaces space—his sculpture surrounds and encloses space; he reintroduced color into sculpture, both overall, unified color that minimizes the role of representation and establishes the sculpture's self-sufficiency as an art object, as well as color used for optical effect or as a means of clarifying structure; and he explored the use of planar material like sheet metal and plywood, which required a new schematic, rather than descriptive, approach to sculptural mass. Finally, he was a born tinkerer who created a medium of his own, the sculpto-painting." (13)

After the war, in 1918, Archipenko returned to Paris and enjoyed a rigorous exhibition schedule featuring his sculpto-paintings and sculptural works incorporating voids. From 1919 through 1923 he had eight one-man shows along with participating in numerous group shows. Much of this is a result of joining forces with fellow artists Gleizes and Léopold Survage (French 1879–1968) to found La Section d'Or, an association of various artists from different backgrounds. The goal of La Section d'Or was the creation of exhibition and performance opportunities at home and abroad. For Archipenko, this venture culminated in his representation of Ukraine in the Venice Biennale of 1920 and solo exhibitions of his work at the Kunsthaus, Zurich and Librarire Kundig, Geneva in Switzerland in 1919 and at the Société Anonyme, Inc. in New York in 1921. (14)

A touring exhibition of his work around five cities in Germany and a retrospective in the city of Potsdam brought Archipenko to Berlin, where he relocated in 1921. At that time, he opened a new art school and tirelessly worked to promote his work through exhibitions along with publishing the monograph, Archipenko Album, the first of six monographs produced during his time in Germany. Additionally, Archipenko continued his interest in printmaking creating, in 1921, the portfolio, Alexandre Archipenko: Dreizehn Steinzeichnungen (translated as thirteen stone carvings, or thirteen lithographs) with the publisher Verlag Ernst Wasmuth. Michaelsen suggests that much of Archipenko's success during his time in Germany was a direct result of his new marriage to German artist Angelica Schmitz in 1921. A sculptor, also known by the name Gela Forster, Schmitz came from a respected artistic lineage, her father was a well-respected architect, and her grandfather a well-regarded painter. Additionally, Schmitz was a founding member of the Sezession Gruppe alongside artists Otto Dix (German 1891–1969), Conrad Felixmüller (German, 1897–1977), and Ludwig Meidner (German, 1884–1966). As such, his marriage allowed Archipenko immediate acceptance into a thriving artistic community.

Once in Berlin, Archipenko's style morphed from the abstract avant-garde works he created in Paris to embody a more naturalistic approach in line with public preferences. Though perhaps in keeping with local attitudes, the works failed with art critics. For example, Hans Hildebradnt condemned Archipenko for "bending his great talent under the yoke of public taste which always favors sweet prettiness and a style of virtuoso naturalism." (15) Although removed stylistically from the innovative works produced in Paris, Archipenko kept close to his love and fasciation with the female form in his new sculptures. Whether abstracted or rendered more realistically, the female body is the touchstone that he returned to over and over. It is "the type of figure most commonly identified today with Archipenko: a female torso with a flowing arabesque contour. Repeatedly throughout his career, Archipenko returned to this universally pleasing motif. Whether vertical or horizontal, or merely suggested by an S-shaped outline, the curvilinear female torso is the formal idée fixe in Archipenko's work." (16)

After a few years in Germany, Archipenko and his wife decided to set sail for America. In the post-war years, Germany, along with the rest of Europe, faced extremely difficult economic conditions and Archipenko longed to escape to a place where he could create in a more conducive environment. Shortly after his and Schmitz' arrival in New York in 1923, Archipenko once again established an art school with the ideal of "creating the only modern art school in the world." (17) Adapting to a new country, Archipenko began substituting English titles for his work as a way to try to appeal to American audiences. (18) Once in New York, Archipenko continued to show in various exhibitions including at the Société Anonyme, but his sculpto-paintings, Cubist sculptures, and naturalistic figures received little critical acclaim and few sales resulting in financial difficulties for the couple despite his teaching salary. In the meantime, Archipenko traveled briefly to Washington D. C. to complete commissioned portrait busts of the Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes and Illinois Senator Medill McCormick.

Funneling all his creative energies into a new endeavor, Archipenko finally followed in his father's footsteps by becoming an inventor with his creation, the Archipentura machine. After many years spent on the design, and patented in 1927, Archipenko debuted his invention in a solo exhibition of his work at the Anderson Galleries in 1928. Archipenko described the machine in the following way:

"Archipentura is neither a theory nor a dogma. It is an emotional

creation...

Archipentura is differentiated from ordinary painting in that it is

dynamic, and not static.

Archipentura is the concrete union of painting with time and space.

Archipentura is the most perfect form of modern art, for it has

solved the problem of dynamism...

Archipentura is the art of painting on canvas the true action...of a

moment given by movements.

Archipentura is a new means of painting done direct by the artist,

in perfect subordination to his will or his creative emotions." (19)

In practical terms, Archipenko described Archipentura in the catalogue thusly:

"The machine has a box-like shape. Two opposite sides of it are three feet by seven feet. Each of these sides consists of 110 narrow metallic strips, three feet long and one half inch thick. The strips are installed one on top of another, similar to a Venetian blind. These two sides become the panels for the display of paintings. They are about two feet from each other, and 110 pieces of strong canvas, running horizontally encircle two oppositely fixed strips. Both ends of the canvases are fastened in the central frame located between two display panels. By mechanically moving the central frame, all 110 canvases simultaneously slide over all the metallic strips, making both panels gradually change their entire surface on which an object is painted. A new portion of specially painted canvas constantly appears. This produced the effect of true motion. A patented method of painting is used to obtain motion. An electrical mechanism in the bottom of the apparatus moves the central frame back and forth, and thousands of consecutive painted fragments appear on the surface to form a total picture. It is not the subject matter, but the changes, which become the essence and lie at the origin of this invention." (20)

While this type of design may be familiar to today's general public from recognizable rotating slat billboards, (21) at the time, and despite Archipenko's hopes for its adaptation for commercial functions, Archipentura was not a success. It was only shown once more during the evening event Art of the Future held at the Société Anonyme on March 23, 1931. Sometime between 1935 and 1939 the machine was accidentally destroyed while in storage.

Following the creation of Archipentura, in 1929, Archipenko became an American citizen. Several years later, in 1935 he moved to California where he once again opened an art school, his fourth, in Hollywood. After a short two years, he moved once again in 1937 to Chicago. In the fall of that year, he opened his fifth school while also assuming the duties of a faculty member in Laszlo Mohly-Nagy's New Bauhaus School of Design. This again was short lived, and by 1939, Archipenko found himself back in New York and reopening his old school. His love of teaching continued to sustain Archipenko, and beginning in the 1950s and up until the time of his death, February 25, 1964 (22) he travelled throughout the United States to teach at various universities.

As he began working as a visiting lecturer in 1950, Archipenko also received a commission for two lithographic portraits from the Associated American Artists. This provided the opportunity to return to printmaking after a gap in working in this medium. In fact, this was the first time Archipenko made prints since he arrived in the United States. During this period, in 1955, a large exhibition of Archipenko's works travelled in Germany, renewing interest in his works in Europe. A few years later, in 1957, his wife Angelica Schmitz died. Archipenko found a new partner in the artist Frances Gray whom he married in 1960.

Archipenko enjoyed much success and public acclaim during his lifetime, but his personality, his ego, and his methods did not always aid in this. For example, Archipenko remade several versions of his works, but chose to date these later works with the earlier date of the original piece. This lack of transparency with his dating caused confusion and controversy, and in fact, led to a feud with Alfred H. Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Barr invited Archipenko to participate in the group exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art. Archipenko provided replicas of the originals that Barr' requested, but was not forthcoming about this fact. While these were not true replicas in that Archipenko created new works based upon memory and photographs and thus, were not exact copies, Barr felt frustrated and deceived. Looking back, this ultimately had little impact on the lasting influence of Archipenko. His contributions to modern art were numerous and lasting.

J. Jankauskas

10/14/14

(1) Resources pertaining to Archipenko's work are numerous. Primary sources for this essay come from the following: Information on file, (Artist's Vertical File, MMFA Library and MMFA Objects Record File: 2007.0003.0004-14) Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL; The Archipenko Foundation, http://www.archipenko.org/; Goldberg, Deborah A., Alexander Archipenko: The Sculptor as Printmaker, NY: Zabriskie Gallery, 1990; Donald Karshan, Archipenko, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, 1908–1963, Danville, KY: Centre College, 1985; Donald Karshan, Archipenko: The Sculpture and Graphic Art, Including a Print Catalogue Raisonné, Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth, 1974; and Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986.

(2) Deborah A. Goldberg, Alexander Archipenko: The Sculptor as Printmaker, NY: Zabriskie Gallery, 1990, p.7.

(3) Michaelson suggests that it was this sculpture, an idol made prior to Ukraine's conversion to Christianity and their ban on sculpture, that later steered Archipenko towards favoring masterpieces of Byzantine, Gothic, and archaic art. Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 18-19.

(4) Ibid, p. 18.

(5) His father, Porfiry Antonowych Archipenko, an inventor and engineer, built a fortune through a furnace design that cleansed the air of polluting factory fumes.

(6)Alexander Archipenko, quoted in Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 21.

(7) Donald Karshan, Archipenko, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, 1908–1963, Danville, KY: Centre College, 1985, pg. 3.

(8) Goldberg, p. 9.

(9) Goldberg, p. 1. However, there appears to be a discrepancy in the number of prints attributed to Archipenko. In her footnote no. 1, p.8, Goldberg states, "David Tunick, in his Review of Donald Karshan's book, adds two more prints to Karshan's Catalogue Raisonné. Review of Donald Karshan, Archipenko: The Sculpture and Graphic Art, Including a Print Catalogue Raisonné (Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth, 1974) in the Print Collector's Newsletter, vol. vii, No. 4 (September–October 1976), pp. 124-125.

(10) Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 45.

(11) Ibid, p. 29. These works were, Carrousel Pierrot, Boxing, and Medrano II, and Magnelli kept them in his collection until the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum purchased them in 1957.

(12) Ibid, p. 18.

(13) Ibid, pp. 45-46.

(14) The Société Anonyme was a gallery founded by Katherine Drier in conjunction with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray (American, born Emmanuel Radnitzky, 1890 –1976). The mission of the gallery was to introduce avant-garde artists to an American audience.

(15) Hans Hildebrandt, quoted in Michaelson, p. 55.

(16) Michaelsen, p. 23.

(17) Archipenko quoted in Michaelsen, p. 58.

(18) Karshan, p. 3.

(19) Archipenko quoted in Michaelsen, p. 65.

(20) Ibid, p. 66.

(21) Yet even slat billboards are becoming obsolete with the advent of digital technology.

(22) This is the date given by the Archipenko Foundation on their timeline. Other sources list Archipenko's death date as February 26, 1964.

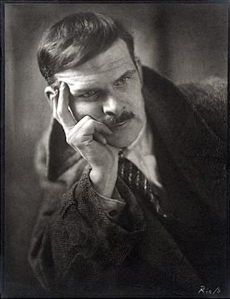

Image credit: Atelier Riess, Alexander Archipenko, ca. 1920, Alexander Archipenko papers, 1904-1986. Photograph courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

American, born Ukraine

(Kiev, Ukraine, 1887 - 1964, New York, New York)

Born on May 30, 1887 in Kiev, Ukraine, Alexander Archipenko (Aleksandr Porfirevich Arkhipenko) had an early exposure to art. (1) He often witnessed his grandfather painting icons for the Orthodox Church (2) and, as a young boy, Archipenko encountered a work that would make a great impression on him, an early idol sculpture in the gardens of the University of Kiev where his father worked.(3) These early experiences made an impact and influenced his thinking about art in adulthood. Another memory from his childhood demonstrates how he developed critical thinking in regard to how objects occupy space. He recalls his parents bringing home two identical vases and,

"that as he looked at them, he was seized by the urge to place them close to each other. No sooner had he done this, he discovered a third, immaterial vase formed by the space between the first two." (4)

This discovery was important for Archipenko and would later influence his work greatly. However, prior to developing his innovative sculptural ideas, Archipenko needed to learn more about art. Growing up in an affluent family, Archipenko had many opportunities available to him. (5) Yet, his choice to pursue art caused a strain in his relationship with his father, who had hoped that Archipenko would follow in his footsteps as an engineer and inventor. Instead, during his teenage years from 1902–1905, Archipenko studied painting and sculpture at the School of Art in Kiev. The conservative atmosphere of his class, however, aggravated his sensibilities, and he protested the system along with some of his classmates, leading to his expulsion. The following year, in 1906, Archipenko struck out on his own and moved to Moscow. It was here that he began to have some success with his art, participating in several group exhibitions and showing his reductive figurative works that often had missing body parts or that focused on partial forms.

In 1908, at the age of 21, Archipenko left Russia for good, moving to Paris, France. In Paris, Archipenko's education continued on an informal basis. He enrolled at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but dropped out after two weeks. Instead, he immersed himself in the city's rich museum and artistic community where his ideas really began to expand. Spending time at the Louvre, taking in Byzantine, Gothic, and archaic art along with examples of primitive and folk artists, influenced Archipenko immensely. Additionally, Archipenko simultaneously began frequenting cafes and artists' colonies including La Ruche, becoming close friends with many of the artists, critics, and poets at the forefront of artistic thinking that brought forward Cubism. The spirit of intellectual and artistic exchange energized Archipenko and his associations with artists such as Fernand Léger (French, 1881–1955), Robert Delaunay (French, 1885–1941), Henri Le Fauconnier (French, 1881–1946), Albert Gleizes (French 1881–1953), and Jean Metzinger (French, 1883–1956) helped foster his career. In 1910, Archipenko exhibited alongside cubist painters at the Salon des Indépendants. This exhibition was not only one of the first exhibitions to feature cubist works but it also served as Archipenko's first exhibition in Paris. He included five sculptures and one painting, and while never fully embracing Cubism, Archipenko did incorporate several cubist elements within his works. For example, he reduced body parts into essential angular elements along with referencing archaic and primitive works.

After his inclusion within the Salon des Indépendants, Archipenko entered a period of intense productivity and an evolution in style spurred on by the support and promotion of friends and critics Guillaume Apollinaire (French 1880–1918) and Blaise Cendrars (Swiss, 1887–1961). In 1911, Archipenko became part of a Cubist group that included the Duchamp brothers (Jacques Villon, [French, 1875–1963] Raymond Duchamp Villon [French, 1876–1918] and Marcel Duchamp [French, 1887–1968]) along with other friends including Gleizes, Leger, Le Fauconnier, Metzinger, and Francis Picabia (French, 1879–1953). He often exhibited alongside these artists, showing in the Salon d'Automne from 1911 to 1913. During this period, in 1912, Archipenko opened his first art school, a pursuit that he followed at multiple times in many locales, teaching extensively throughout his life.

Archipenko's style during this period developed from his rejection of Auguste Rodin's (French, 1840–1917) sculptural techniques. Although Rodin's expressionistic works were well regarded at the time, Archipenko stated, "I hated Rodin, who was then fashionable. His sculptures reminded me of chewed bread that one spits on a base, or the crooked corpses from Pompeii." (6) Instead, inspired by the Cubists and Italian Futurists, Archipenko forged new ground with his sculptures by incorporating collage and using nontraditional materials such as a combination of bronze, found objects, glass, mirrors, plastic, and sheet metal. By 1912, he fully embraced the combination of these different materials and began working in the interstices of two- and three-dimensions. The years 1913–1914 were pivotal for Archipenko. In 1913, four plaster sculptural works along with five works on paper by him were included in the seminal International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York, otherwise known as the Armory Show, which also traveled to Boston and Chicago. This exhibition shocked and scandalized many Americans who were comfortable and familiar with realistic art, rather then the modern works on view. Though controversial at the time, the exhibition enjoys a lasting legacy, and it influenced many American artists while creating a new audience for modern art in the U.S. Additionally, some of the works of art, including Archipenko's, found homes with American collectors interested in the new progressive styles of European artists. While Archipenko's sculptures failed to find buyers, artist and dealer Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946) purchased all five drawings and continued to support Archipenko's work over the course of many years.

Additionally in 1913, Archipenko embraced another art form, that of printmaking. He worked in a variety of printmaking techniques including lithography, drypoint, silk-screen, embossing, and etching. His first print was a lithograph entitled Abstraction (Seated Figure), featuring abstracted forms rendered in a futuristic style. This print later served as an inspiration for the 1959 sculpture, Abstraction. This is often how Archipenko worked, returning to earlier ideas and creating a symbiotic relationship between his drawings, prints, and sculptural works. As he explored his ideas in one medium it would spur ideas for exploration in another format. Remarking on the relationship between the works on paper and the sculptures, Archipenko scholar Donald Karshan states, "Archipenko's works on paper were either studies for or analysis and refinement after his three-dimensional investigations." (7) Curator Deborah A. Goldberg continues, "With its great spontaneity and diversity, printmaking gave Archipenko a further outlet for expression. He learned to manipulate the unique effects of this medium to produce what could not be achieved in a drawing alone." (8) While Archipenko enjoyed working both sculpturally and on paper, his printmaking output is small in comparison to his prolific three-dimensional legacy. Creating prints sporadically throughout his career, Archipenko only produced a total of 54 prints from 1913 until 1963. (9)

Also during 1913 and 1914, Archipenko also made many of his most important sculptures including Carosel Pierrot (1913), Medrano II (1913), and Boxing (1914). At the spring 1914 Salon des Indépendants exhibition, Archipenko showed these works alongside Gondolier (1914). Singled out by Apollinaire, these works caused a stir in society for Archipenko's inventive use of materials. (10) Despite the controversy, three of the works found a buyer, the Italian painter, Alberto Magnelli (1888–1971). (11)

Late in 1914, due to the encroachment of World War I on Paris, Archipenko left for Nice, in the south of France. At this time, he began heavily experimenting with what he termed "sculpto-paintings," a fusion of both painting and sculpture. These works, polychrome bronzes that brought sculptural relief elements to the two-dimensional plane, became not only a signature style for Archipenko but also a significant contribution to modern sculpture. The sculpto-paintings varied in format; some consist of assemblage while others are painted reliefs in plaster or papier-mâché. Creating almost forty scupto-paintings during the war years, Archipenko returned to this process again in the 1950s. Additionally, going back to his early memory of the two vases from his childhood, Archipenko began incorporating voids into his works as a "'symbol' for an absent volume." (12) By playing with mass and void, the convex and the concave, and light and shadows, Archipenko fully exploited the shape and form of the absent material as much as what was present. This invention of the void in sculpture became one of his seminal achievements in modern art and is seen in many works over a period of several years beginning in 1914 including Seated Woman, 1920. Art historian Katherine Michaelson, calls Archipenko a "pioneer of modern sculpture," and succinctly summarizes his contributions to modern art:

"He initiated the opening-up of sculpture, not just by piercing a hole into it, but by presenting an alternative to the traditional notion of the monolith that merely displaces space—his sculpture surrounds and encloses space; he reintroduced color into sculpture, both overall, unified color that minimizes the role of representation and establishes the sculpture's self-sufficiency as an art object, as well as color used for optical effect or as a means of clarifying structure; and he explored the use of planar material like sheet metal and plywood, which required a new schematic, rather than descriptive, approach to sculptural mass. Finally, he was a born tinkerer who created a medium of his own, the sculpto-painting." (13)

After the war, in 1918, Archipenko returned to Paris and enjoyed a rigorous exhibition schedule featuring his sculpto-paintings and sculptural works incorporating voids. From 1919 through 1923 he had eight one-man shows along with participating in numerous group shows. Much of this is a result of joining forces with fellow artists Gleizes and Léopold Survage (French 1879–1968) to found La Section d'Or, an association of various artists from different backgrounds. The goal of La Section d'Or was the creation of exhibition and performance opportunities at home and abroad. For Archipenko, this venture culminated in his representation of Ukraine in the Venice Biennale of 1920 and solo exhibitions of his work at the Kunsthaus, Zurich and Librarire Kundig, Geneva in Switzerland in 1919 and at the Société Anonyme, Inc. in New York in 1921. (14)

A touring exhibition of his work around five cities in Germany and a retrospective in the city of Potsdam brought Archipenko to Berlin, where he relocated in 1921. At that time, he opened a new art school and tirelessly worked to promote his work through exhibitions along with publishing the monograph, Archipenko Album, the first of six monographs produced during his time in Germany. Additionally, Archipenko continued his interest in printmaking creating, in 1921, the portfolio, Alexandre Archipenko: Dreizehn Steinzeichnungen (translated as thirteen stone carvings, or thirteen lithographs) with the publisher Verlag Ernst Wasmuth. Michaelsen suggests that much of Archipenko's success during his time in Germany was a direct result of his new marriage to German artist Angelica Schmitz in 1921. A sculptor, also known by the name Gela Forster, Schmitz came from a respected artistic lineage, her father was a well-respected architect, and her grandfather a well-regarded painter. Additionally, Schmitz was a founding member of the Sezession Gruppe alongside artists Otto Dix (German 1891–1969), Conrad Felixmüller (German, 1897–1977), and Ludwig Meidner (German, 1884–1966). As such, his marriage allowed Archipenko immediate acceptance into a thriving artistic community.

Once in Berlin, Archipenko's style morphed from the abstract avant-garde works he created in Paris to embody a more naturalistic approach in line with public preferences. Though perhaps in keeping with local attitudes, the works failed with art critics. For example, Hans Hildebradnt condemned Archipenko for "bending his great talent under the yoke of public taste which always favors sweet prettiness and a style of virtuoso naturalism." (15) Although removed stylistically from the innovative works produced in Paris, Archipenko kept close to his love and fasciation with the female form in his new sculptures. Whether abstracted or rendered more realistically, the female body is the touchstone that he returned to over and over. It is "the type of figure most commonly identified today with Archipenko: a female torso with a flowing arabesque contour. Repeatedly throughout his career, Archipenko returned to this universally pleasing motif. Whether vertical or horizontal, or merely suggested by an S-shaped outline, the curvilinear female torso is the formal idée fixe in Archipenko's work." (16)

After a few years in Germany, Archipenko and his wife decided to set sail for America. In the post-war years, Germany, along with the rest of Europe, faced extremely difficult economic conditions and Archipenko longed to escape to a place where he could create in a more conducive environment. Shortly after his and Schmitz' arrival in New York in 1923, Archipenko once again established an art school with the ideal of "creating the only modern art school in the world." (17) Adapting to a new country, Archipenko began substituting English titles for his work as a way to try to appeal to American audiences. (18) Once in New York, Archipenko continued to show in various exhibitions including at the Société Anonyme, but his sculpto-paintings, Cubist sculptures, and naturalistic figures received little critical acclaim and few sales resulting in financial difficulties for the couple despite his teaching salary. In the meantime, Archipenko traveled briefly to Washington D. C. to complete commissioned portrait busts of the Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes and Illinois Senator Medill McCormick.

Funneling all his creative energies into a new endeavor, Archipenko finally followed in his father's footsteps by becoming an inventor with his creation, the Archipentura machine. After many years spent on the design, and patented in 1927, Archipenko debuted his invention in a solo exhibition of his work at the Anderson Galleries in 1928. Archipenko described the machine in the following way:

"Archipentura is neither a theory nor a dogma. It is an emotional

creation...

Archipentura is differentiated from ordinary painting in that it is

dynamic, and not static.

Archipentura is the concrete union of painting with time and space.

Archipentura is the most perfect form of modern art, for it has

solved the problem of dynamism...

Archipentura is the art of painting on canvas the true action...of a

moment given by movements.

Archipentura is a new means of painting done direct by the artist,

in perfect subordination to his will or his creative emotions." (19)

In practical terms, Archipenko described Archipentura in the catalogue thusly:

"The machine has a box-like shape. Two opposite sides of it are three feet by seven feet. Each of these sides consists of 110 narrow metallic strips, three feet long and one half inch thick. The strips are installed one on top of another, similar to a Venetian blind. These two sides become the panels for the display of paintings. They are about two feet from each other, and 110 pieces of strong canvas, running horizontally encircle two oppositely fixed strips. Both ends of the canvases are fastened in the central frame located between two display panels. By mechanically moving the central frame, all 110 canvases simultaneously slide over all the metallic strips, making both panels gradually change their entire surface on which an object is painted. A new portion of specially painted canvas constantly appears. This produced the effect of true motion. A patented method of painting is used to obtain motion. An electrical mechanism in the bottom of the apparatus moves the central frame back and forth, and thousands of consecutive painted fragments appear on the surface to form a total picture. It is not the subject matter, but the changes, which become the essence and lie at the origin of this invention." (20)

While this type of design may be familiar to today's general public from recognizable rotating slat billboards, (21) at the time, and despite Archipenko's hopes for its adaptation for commercial functions, Archipentura was not a success. It was only shown once more during the evening event Art of the Future held at the Société Anonyme on March 23, 1931. Sometime between 1935 and 1939 the machine was accidentally destroyed while in storage.

Following the creation of Archipentura, in 1929, Archipenko became an American citizen. Several years later, in 1935 he moved to California where he once again opened an art school, his fourth, in Hollywood. After a short two years, he moved once again in 1937 to Chicago. In the fall of that year, he opened his fifth school while also assuming the duties of a faculty member in Laszlo Mohly-Nagy's New Bauhaus School of Design. This again was short lived, and by 1939, Archipenko found himself back in New York and reopening his old school. His love of teaching continued to sustain Archipenko, and beginning in the 1950s and up until the time of his death, February 25, 1964 (22) he travelled throughout the United States to teach at various universities.

As he began working as a visiting lecturer in 1950, Archipenko also received a commission for two lithographic portraits from the Associated American Artists. This provided the opportunity to return to printmaking after a gap in working in this medium. In fact, this was the first time Archipenko made prints since he arrived in the United States. During this period, in 1955, a large exhibition of Archipenko's works travelled in Germany, renewing interest in his works in Europe. A few years later, in 1957, his wife Angelica Schmitz died. Archipenko found a new partner in the artist Frances Gray whom he married in 1960.

Archipenko enjoyed much success and public acclaim during his lifetime, but his personality, his ego, and his methods did not always aid in this. For example, Archipenko remade several versions of his works, but chose to date these later works with the earlier date of the original piece. This lack of transparency with his dating caused confusion and controversy, and in fact, led to a feud with Alfred H. Barr, the director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Barr invited Archipenko to participate in the group exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art. Archipenko provided replicas of the originals that Barr' requested, but was not forthcoming about this fact. While these were not true replicas in that Archipenko created new works based upon memory and photographs and thus, were not exact copies, Barr felt frustrated and deceived. Looking back, this ultimately had little impact on the lasting influence of Archipenko. His contributions to modern art were numerous and lasting.

J. Jankauskas

10/14/14

(1) Resources pertaining to Archipenko's work are numerous. Primary sources for this essay come from the following: Information on file, (Artist's Vertical File, MMFA Library and MMFA Objects Record File: 2007.0003.0004-14) Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Montgomery, AL; The Archipenko Foundation, http://www.archipenko.org/; Goldberg, Deborah A., Alexander Archipenko: The Sculptor as Printmaker, NY: Zabriskie Gallery, 1990; Donald Karshan, Archipenko, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, 1908–1963, Danville, KY: Centre College, 1985; Donald Karshan, Archipenko: The Sculpture and Graphic Art, Including a Print Catalogue Raisonné, Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth, 1974; and Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986.

(2) Deborah A. Goldberg, Alexander Archipenko: The Sculptor as Printmaker, NY: Zabriskie Gallery, 1990, p.7.

(3) Michaelson suggests that it was this sculpture, an idol made prior to Ukraine's conversion to Christianity and their ban on sculpture, that later steered Archipenko towards favoring masterpieces of Byzantine, Gothic, and archaic art. Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 18-19.

(4) Ibid, p. 18.

(5) His father, Porfiry Antonowych Archipenko, an inventor and engineer, built a fortune through a furnace design that cleansed the air of polluting factory fumes.

(6)Alexander Archipenko, quoted in Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 21.

(7) Donald Karshan, Archipenko, Sculpture, Drawings and Prints, 1908–1963, Danville, KY: Centre College, 1985, pg. 3.

(8) Goldberg, p. 9.

(9) Goldberg, p. 1. However, there appears to be a discrepancy in the number of prints attributed to Archipenko. In her footnote no. 1, p.8, Goldberg states, "David Tunick, in his Review of Donald Karshan's book, adds two more prints to Karshan's Catalogue Raisonné. Review of Donald Karshan, Archipenko: The Sculpture and Graphic Art, Including a Print Catalogue Raisonné (Tübingen: Ernst Wasmuth, 1974) in the Print Collector's Newsletter, vol. vii, No. 4 (September–October 1976), pp. 124-125.

(10) Katherine Jánszky Michaelsen, "Alexander Archipenko: 1887–1964," Alexander Archipenko: A Centennial Tribute, Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1986, p. 45.

(11) Ibid, p. 29. These works were, Carrousel Pierrot, Boxing, and Medrano II, and Magnelli kept them in his collection until the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum purchased them in 1957.

(12) Ibid, p. 18.

(13) Ibid, pp. 45-46.

(14) The Société Anonyme was a gallery founded by Katherine Drier in conjunction with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray (American, born Emmanuel Radnitzky, 1890 –1976). The mission of the gallery was to introduce avant-garde artists to an American audience.

(15) Hans Hildebrandt, quoted in Michaelson, p. 55.

(16) Michaelsen, p. 23.

(17) Archipenko quoted in Michaelsen, p. 58.

(18) Karshan, p. 3.

(19) Archipenko quoted in Michaelsen, p. 65.

(20) Ibid, p. 66.

(21) Yet even slat billboards are becoming obsolete with the advent of digital technology.

(22) This is the date given by the Archipenko Foundation on their timeline. Other sources list Archipenko's death date as February 26, 1964.

Image credit: Atelier Riess, Alexander Archipenko, ca. 1920, Alexander Archipenko papers, 1904-1986. Photograph courtesy of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Artist Objects