Bill Traylor

American

(Pleasant Hill, Dallas County, Alabama, 1853 - 1949, Montgomery, Alabama)

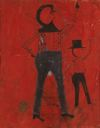

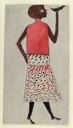

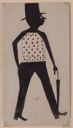

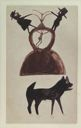

When Bill Traylor came to Montgomery in the late 1930s, he brought with him a lifetime of experience and memories that became the basis for an amazing body of work. In a relatively short time, between about 1938 and 1942, Traylor produced some 1,500 drawings that resonate with the indomitable spirit of this elderly African-American man who had been born into slavery before the Civil War. Traylor lived most of his working life as a laborer on the Traylor family farm in the rural area near Benton, Alabama, about forty miles west of Montgomery. The land had been cultivated as a cotton plantation since its settlement in the early 1820s by John G. Traylor, who had migrated from South Carolina. Around 1938, Bill Traylor—now an 82-year-old widower, with his twenty or more children dispersed—left for Montgomery, where he got a job in a shoe factory. After rheumatism forced him to abandon this work, he spent his days on the street, passing time by making drawings on discarded scraps of cardboard and sleeping in a local funeral parlor. (1) Boxboard containers that once held notions or candy, stubs of pencils, and poster paint comprised Traylor’s sparse resources. The paints came from a young white artist, Charles Shannon, who spied Traylor drawing in a doorway in the summer of 1939. Shannon later described what he saw as he came back day after day to admire the products of pure artistic expression: “He was depicting objects; shoes and cups were arranged neatly in rows. On the following day he was making his version of a nearby blacksmith shop; a man was shoeing a horse in one corner and the tools of the shop were distributed in orderly silhouette across the horizontal panel. Then came his drawing of the drinking bout: a lot of little people were shown drinking and scurrying about a huge keg. The drinking theme was to recur often. He apparently had seen a lot of it, but as for himself he said, ‘What little sense I did have it took away.’” (2) Traylor’s drawings evoke his earlier years on the plantation, but they also record what he saw daily on the street. He stationed himself adjacent to a busy fruit stand, near the entrance of a building that housed the Pekin Pool Room. (A large parking deck now occupies the site.) In Traylor’s time, this area was the center of black life and culture in Montgomery, teeming with people going about their daily chores and engaged in commerce. Traylor’s numerous portraits of local men and women dressed in their Sunday best, walking dogs, smoking, or arguing, and of travelers with suitcases in hand, indicate that his observations of the passing scene were as important to his art as his memories of rural life. (3)

Bill Traylor first came to the attention of the wider art world in 1982, when his work was included in the landmark exhibition “Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980.” Organized by the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC, this show brought together works by artists designated as “self-taught” or “outsiders,” whose creations were rooted in traditional, mostly rural African-American ways of life. Traylor’s drawings attracted particular attention and subsequently became prominent in a movement geared toward collecting, preserving, and interpreting the creations of these hitherto unrecognized artists. Their work has since come to be seen as a counterpoint to the development of Modernism in art of the twentieth century. (4)

(1) 1. For information on Bill Traylor’s life, see Andrea L. Potochick, “Bill Traylor—African American Outsider Artist,” MA thesis, Florida State University School of Visual Arts and Dance, 1992. After emancipation, it was customary for black families to take the name of the family who owned the land on which they were born or lived.

(2) 2. See Charles Shannon, “The Folk Art of Bill Traylor,” in Richard Cox, Southern Works on Paper, 1900–1950 (Montgomery: The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1981), p. 16.

(3) Margaret Lynne Ausfeld, “’A World Unto Itself’: Bill Traylor’s Montgomery,” in Josef Helfenstein et al., Bill Traylor, William Edmondson and the Modernist Impulse (Urbana-Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2004), p. 90.

(4) Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, University Press of Mississippi, and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, 1982).

American Paintings from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 2006, cat. no. 33

American

(Pleasant Hill, Dallas County, Alabama, 1853 - 1949, Montgomery, Alabama)

When Bill Traylor came to Montgomery in the late 1930s, he brought with him a lifetime of experience and memories that became the basis for an amazing body of work. In a relatively short time, between about 1938 and 1942, Traylor produced some 1,500 drawings that resonate with the indomitable spirit of this elderly African-American man who had been born into slavery before the Civil War. Traylor lived most of his working life as a laborer on the Traylor family farm in the rural area near Benton, Alabama, about forty miles west of Montgomery. The land had been cultivated as a cotton plantation since its settlement in the early 1820s by John G. Traylor, who had migrated from South Carolina. Around 1938, Bill Traylor—now an 82-year-old widower, with his twenty or more children dispersed—left for Montgomery, where he got a job in a shoe factory. After rheumatism forced him to abandon this work, he spent his days on the street, passing time by making drawings on discarded scraps of cardboard and sleeping in a local funeral parlor. (1) Boxboard containers that once held notions or candy, stubs of pencils, and poster paint comprised Traylor’s sparse resources. The paints came from a young white artist, Charles Shannon, who spied Traylor drawing in a doorway in the summer of 1939. Shannon later described what he saw as he came back day after day to admire the products of pure artistic expression: “He was depicting objects; shoes and cups were arranged neatly in rows. On the following day he was making his version of a nearby blacksmith shop; a man was shoeing a horse in one corner and the tools of the shop were distributed in orderly silhouette across the horizontal panel. Then came his drawing of the drinking bout: a lot of little people were shown drinking and scurrying about a huge keg. The drinking theme was to recur often. He apparently had seen a lot of it, but as for himself he said, ‘What little sense I did have it took away.’” (2) Traylor’s drawings evoke his earlier years on the plantation, but they also record what he saw daily on the street. He stationed himself adjacent to a busy fruit stand, near the entrance of a building that housed the Pekin Pool Room. (A large parking deck now occupies the site.) In Traylor’s time, this area was the center of black life and culture in Montgomery, teeming with people going about their daily chores and engaged in commerce. Traylor’s numerous portraits of local men and women dressed in their Sunday best, walking dogs, smoking, or arguing, and of travelers with suitcases in hand, indicate that his observations of the passing scene were as important to his art as his memories of rural life. (3)

Bill Traylor first came to the attention of the wider art world in 1982, when his work was included in the landmark exhibition “Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980.” Organized by the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington, DC, this show brought together works by artists designated as “self-taught” or “outsiders,” whose creations were rooted in traditional, mostly rural African-American ways of life. Traylor’s drawings attracted particular attention and subsequently became prominent in a movement geared toward collecting, preserving, and interpreting the creations of these hitherto unrecognized artists. Their work has since come to be seen as a counterpoint to the development of Modernism in art of the twentieth century. (4)

(1) 1. For information on Bill Traylor’s life, see Andrea L. Potochick, “Bill Traylor—African American Outsider Artist,” MA thesis, Florida State University School of Visual Arts and Dance, 1992. After emancipation, it was customary for black families to take the name of the family who owned the land on which they were born or lived.

(2) 2. See Charles Shannon, “The Folk Art of Bill Traylor,” in Richard Cox, Southern Works on Paper, 1900–1950 (Montgomery: The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1981), p. 16.

(3) Margaret Lynne Ausfeld, “’A World Unto Itself’: Bill Traylor’s Montgomery,” in Josef Helfenstein et al., Bill Traylor, William Edmondson and the Modernist Impulse (Urbana-Champaign, IL: Krannert Art Museum, 2004), p. 90.

(4) Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, University Press of Mississippi, and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, 1982).

American Paintings from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 2006, cat. no. 33

Artist Objects