Frank M. Spangler, Sr.

American

(Osborne, Ohio, 1881 - 1946, Montgomery, Alabama)

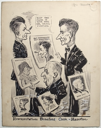

Few cartoonists anywhere in the country commanded more authority of skill and viewpoint than that earned by Frank M. Spangler, Sr. in his forty-one years as editorial cartoonist for the Montgomery Advertiser. Like the political cartoonists who proceeded him, Spangler was passionate about his art, and about issues that inspired it.

Spangler (or Spang as he was known in his printed work) was born in Osborne, Ohio in 1881. In 1901, he attended the Art Student's League and the Chase School of Art in New York City. Beginning his career in the engraving department of the Columbus (OH) Dispatch, he was in the process of trying his hand at editorial cartooning there, when, in 1905, an art school acquaintance left his position at the Montgomery Advertiser, recommending Spangler to replace him. (He left Montgomery only twice to seek advancement—once for about a year in 1909 to draw for The Grit, a Pennsylvania weekly, and a second time in 1917 to work for the Hearst paper Atlanta Georgian-American.)

Spangler was an unabashed booster of Montgomery, but his finest works were those that were inspired by the South's history of poverty and racial intolerance. Spang was guided by the editorial policy of the paper, however his drawings reveal his own stubborn sense of what was right or, more frequently, what was wrong.

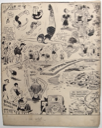

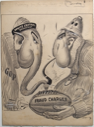

Spangler was the chronicler of an era of momentous change in the South. The forces of modernity that had swept over the nation in the late nineteenth century were engulfing the Alabama of his time. A rural state became more urban, and in places more industrial. Overwhelmingly Protestant, it found itself part of a nation that was increasingly diverse, with great cities populated by immigrants of different religions, customs and cultures. These changes created tension and discord, as the rural population faced economic disaster and saw power, wealth and respect pass into the hands of those so unlike themselves. Religious and racial bigotry flourished among those caught in the toils of these changes.

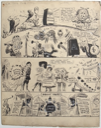

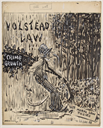

Spangler's most successful works were prompted by this social upheaval, particularly the economic collapse of the early 1930s and the political turmoil that accompanied it. The Alabama economy of that era was dominated, as it had been since the nineteenth century, by King Cotton. The economic welfare of the State rested solely in the market price of that one commodity, and the violent fluctuations in the price of cotton spelled disaster. Reflecting the conservative nature of the population, it was difficult to convince farmers to change the habits of generations and diversify their crops.

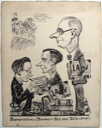

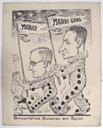

While the editorial board of the Advertiser sought to portray the folly of the "one crop" system, it struggled even more mightily against the conservative, intolerant political climate that flourished in the late 1920s. Images of Thomas J. "Cotton Tom" Heflin dominate some of Spangler's finest cartoons.

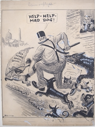

J. Thomas Heflin was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1920 after sixteen years in the U.S. House of Representatives. A native of Chambers County, he had been its representative to the State's constitutional convention in 1901 and had also served as Alabama's Secretary of State. A fanatic on the subject of race and religion, Heflin renounced the national Democratic party in 1928 because he would not support the candidacy of Al Smith, a Roman Catholic, for President. Spangler routinely identifies Heflin with the Republican party by use of an elephant, and with the Klu Klux Klan by repetition of the "hood" shape associated with it. The Advertiser and its editor Grover Hall, Jr. were staunch opponents of both Heflin and the Klan, so that these images were routinely published in numerous variations.

In the early 1940s, Sponge turned his attention to the Second World War. While he was largely interested in matters of local interest for much of his career, the national challenge that the war represented encouraged Spangle to rally the participation of the locals in conservation, war bonds, and other forms of support for the effort.

Spangler worked within a venerable tradition which led artists to comment upon, and sometimes seek to change, societal mores. In earlier times, art commanded more attention than it did in the society of mass communication and, while social consciousness died out as a major theme for fine art, mass communication stepped into the breach to nurture its legacy through the visual satire of editorial and political cartooning. Frank Spangler was an outstanding practitioner of this art, producing the ultimate "art of the common man" that held sway with the breakfast table connoisseurs of central Alabama for forty-one years.

Margaret Lynne Ausfeld, Curator

December 20, 2000

Sources: The biography above is based on the following sources, located in the vertical file for Spangler in the Museum library:

Syd Hoff. Editorial and Political Cartooning. New York: Stravon Educational Press, 1976, pp. 123-126.

The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. Spang: The Editorial and Political Cartoons of Frank M. Spangler, Sr. Montgomery, AL: The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1987. (Essays by Margaret Lynne Ausfeld and William Barnard.)

Jim Upchurch. Spang: Tying the Perfect Knot. Montgomery, April 2-8, 1987. pp. 12-14

"Spells Spang." Alabama Magazine, vol. IV, no. 27 (May 29, 1939) pp. 8-10.

American

(Osborne, Ohio, 1881 - 1946, Montgomery, Alabama)

Few cartoonists anywhere in the country commanded more authority of skill and viewpoint than that earned by Frank M. Spangler, Sr. in his forty-one years as editorial cartoonist for the Montgomery Advertiser. Like the political cartoonists who proceeded him, Spangler was passionate about his art, and about issues that inspired it.

Spangler (or Spang as he was known in his printed work) was born in Osborne, Ohio in 1881. In 1901, he attended the Art Student's League and the Chase School of Art in New York City. Beginning his career in the engraving department of the Columbus (OH) Dispatch, he was in the process of trying his hand at editorial cartooning there, when, in 1905, an art school acquaintance left his position at the Montgomery Advertiser, recommending Spangler to replace him. (He left Montgomery only twice to seek advancement—once for about a year in 1909 to draw for The Grit, a Pennsylvania weekly, and a second time in 1917 to work for the Hearst paper Atlanta Georgian-American.)

Spangler was an unabashed booster of Montgomery, but his finest works were those that were inspired by the South's history of poverty and racial intolerance. Spang was guided by the editorial policy of the paper, however his drawings reveal his own stubborn sense of what was right or, more frequently, what was wrong.

Spangler was the chronicler of an era of momentous change in the South. The forces of modernity that had swept over the nation in the late nineteenth century were engulfing the Alabama of his time. A rural state became more urban, and in places more industrial. Overwhelmingly Protestant, it found itself part of a nation that was increasingly diverse, with great cities populated by immigrants of different religions, customs and cultures. These changes created tension and discord, as the rural population faced economic disaster and saw power, wealth and respect pass into the hands of those so unlike themselves. Religious and racial bigotry flourished among those caught in the toils of these changes.

Spangler's most successful works were prompted by this social upheaval, particularly the economic collapse of the early 1930s and the political turmoil that accompanied it. The Alabama economy of that era was dominated, as it had been since the nineteenth century, by King Cotton. The economic welfare of the State rested solely in the market price of that one commodity, and the violent fluctuations in the price of cotton spelled disaster. Reflecting the conservative nature of the population, it was difficult to convince farmers to change the habits of generations and diversify their crops.

While the editorial board of the Advertiser sought to portray the folly of the "one crop" system, it struggled even more mightily against the conservative, intolerant political climate that flourished in the late 1920s. Images of Thomas J. "Cotton Tom" Heflin dominate some of Spangler's finest cartoons.

J. Thomas Heflin was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1920 after sixteen years in the U.S. House of Representatives. A native of Chambers County, he had been its representative to the State's constitutional convention in 1901 and had also served as Alabama's Secretary of State. A fanatic on the subject of race and religion, Heflin renounced the national Democratic party in 1928 because he would not support the candidacy of Al Smith, a Roman Catholic, for President. Spangler routinely identifies Heflin with the Republican party by use of an elephant, and with the Klu Klux Klan by repetition of the "hood" shape associated with it. The Advertiser and its editor Grover Hall, Jr. were staunch opponents of both Heflin and the Klan, so that these images were routinely published in numerous variations.

In the early 1940s, Sponge turned his attention to the Second World War. While he was largely interested in matters of local interest for much of his career, the national challenge that the war represented encouraged Spangle to rally the participation of the locals in conservation, war bonds, and other forms of support for the effort.

Spangler worked within a venerable tradition which led artists to comment upon, and sometimes seek to change, societal mores. In earlier times, art commanded more attention than it did in the society of mass communication and, while social consciousness died out as a major theme for fine art, mass communication stepped into the breach to nurture its legacy through the visual satire of editorial and political cartooning. Frank Spangler was an outstanding practitioner of this art, producing the ultimate "art of the common man" that held sway with the breakfast table connoisseurs of central Alabama for forty-one years.

Margaret Lynne Ausfeld, Curator

December 20, 2000

Sources: The biography above is based on the following sources, located in the vertical file for Spangler in the Museum library:

Syd Hoff. Editorial and Political Cartooning. New York: Stravon Educational Press, 1976, pp. 123-126.

The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. Spang: The Editorial and Political Cartoons of Frank M. Spangler, Sr. Montgomery, AL: The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1987. (Essays by Margaret Lynne Ausfeld and William Barnard.)

Jim Upchurch. Spang: Tying the Perfect Knot. Montgomery, April 2-8, 1987. pp. 12-14

"Spells Spang." Alabama Magazine, vol. IV, no. 27 (May 29, 1939) pp. 8-10.

Artist Objects