John Singer Sargent

American

(Florence, Italy, 1856 - 1925, London, England)

The life and career of John Singer Sargent present an interesting dichotomy in the history of American art. Born in Italy to American parents, Sargent was an American citizen although he did not set foot in the United States until he was twenty years old.(1) All of his life Sargent lacked stable roots and a place to call home.(2) He was raised speaking English, became fluent in Italian and French and he had a rudimentary knowledge of German. His early nomadic life later reflected his artistic career, for Sargent has never been successfully categorized with one group of artists within the nineteenth or twentieth centuries. Best known for his portraits of affluent aristocrats, Sargent’s work demonstrates a synthesis of nineteenth-century British, French, and American painting. It recalls many styles and periods, but is undoubtedly his own.

Born in Florence, Italy in January 1856, John Singer Sargent was raised in an Anglo-American community. His childhood friend, Vernon Lee, recalled that they played in the garden of Maison Virello, where Dr. and Mrs. Sargent had rented a flat, and in the much larger garden of the nearby Maison Corinaldi. These playgrounds were on the outskirts of the city, an area of palm trees and fig orchards, dwarf rose bushes and empty villas.(3) For ten year-old children, the area served as a perfect place to feed their imaginations, and act out make-believe stories and characters. Sometime around the winter of 1868, Vernon Lee and her family moved and she no longer lived next door to the Sargents. However, Mrs. Sargent made sure that Vernon visited frequently, so that the children could spend their afternoons painting.(4) Vernon recalled that she couldn’t remember if Sargent yet had his own box of paints since he often used hers. While she was making mere pictographs, she remembered that Sargent, with “miraculous intuition and dexterity,” made pictures of ships at sea and houses.(5)

Although Sargent’s father often tried to get the artist to devote serious attention to his academic studies, he finally agreed that his son did have an eye for recording nature. Sargent was always attracted to what he could see, not fantasy or imagination. Artistic productivity ran in the Sargent family – the artist’s grandfather was portrayed by John Singleton Copley, "Epes Sargent" (c. 1760, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.) and another descendent, Henry Sargent, studied with American expatriate Benjamin West in his London studio.(6) Sargent’s father, who had a successful medical practice, decided not to stand in the way of his son’s artistic career. In 1874, the family traveled to Paris, for it was the place to be for any aspiring artist.

When the Sargents arrived in Paris, they had missed the first Impressionist exhibit by one day. The years immediately following Sargent’s arrival in France saw the deaths of Camille Corot and Jean-Francis Millet in 1875, and the death of Gustave Courbet in 1877. Paris was teeming with artistic styles such as Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism – all of which worked their way into Sargent’s art. Meanwhile, with the family settled in a hotel, Dr. Sargent and the young artist set off for the atelier of Carolus-Duran.(7)

Sargent had heard of Carolus-Duran through Walter Launt Palmer, who he had sketched with as a youth in Florence. Carolus-Duran specialized in portraiture, “developing a blend of painterly lines and realism with a distinctive and accessible stamp.”(8) Furthermore, Sargent was attracted to Carolus-Duran’s atelier because of its small size, by what Sargent described as the more “gentlemanly” type of students there, and by the degree of personal attention Carolus-Duran gave to his students. Another point was the high ratio of British and American students

Carolus-Duran worked and taught "au premier coup," meaning at the first touch. This means that forms are built on the canvas rapidly without any reworking. The method demanded faithful visual representation, sophisticated and subtle tonal control with fluid and confident handling. Further, the student was never allowed to brush one surface over the other, he must make a tone for each step of a gradation.(9) This method was at odds with academic training, which laid emphasis on carefully controlled contours with smooth and finished picture surfaces.

Sargent quickly gained attention as his skill impressed itself upon his teachers and colleagues. Carolus-Duran was so confident in Sargent’s work that in 1877, when commissioned to paint a large oil for a ceiling in the Palais dux Luxembourg, he enlisted Sargent and another student to help.(10) It was Sargent’s first experience with a government sponsored project with a grand historical theme, which in nineteenth-century Paris was still the highest form of art. In a sign of mutual respect, Carolus-Duran and Sargent painted portraits of one another within the painting. Two years later, Sargent painted a portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879, Sterling and Francis Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA) which served not only as a declaration of independence from his master and marked the end of his apprenticeship, but also ushered in another phase of his education that took him away from Paris.

The early 1880s were pivotal years for Sargent. Highlighted by two important trips, first to Spain and then to Venice, Sargent saw the works of the Spanish masters for the first time. After visiting Spain, Sargent’s work went from being derivative and stifled to more confident, inventive, and charged with creativity. He copied several of Velazquez’s works, including "Las Meninas" (1656, Museo del Prado, Madrid). One of Sargent’s best known works, "El Jaleo" (1882, Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston) was created under the influence of the Spanish Masters. Recalling Velazquez and El Greco, the painting is a depiction of a Spanish dancer in front of musicians, presumably on stage as it is atypically lit from below. Sargent’s also painted the striking portrait of "Dr. Pozzi (Dr. Pozzi at Home)" (1881, UCLA at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Los Angeles) during this period.

Samuel Jean Pozzi (1846-1918) was a French doctor who was killed by a former patient in his drawing room. In the painting, he wears a red dressing gown and white shirt with a finely pleated collar and stands in front of a red draped background. The background, Pozzi’s pose and the tonality are overt references to both Van Dyck and Velazquez, however, Sargent turns tradition on its ear by “subverting a dark, Spanish gravity to a theatrical characterization of a modern society aesthete in a dazzling red on red 'tour de force'.” (11) While today considered one of Sargent’s masterpieces, the work was not well received upon exhibition. Critics thought it was “gaudy, common, unbearable, unharmonious, and untonal.” (12) It would not be the last time Sargent shocked his audience.

The early 1880s also proved to be an experimental time for the artist. He painted numerous portraits of his family and friends, which represent experiments in characterization and technique. Heads loom out of dark backgrounds, with a conscious effect of mystery. Figures are “modeled in a raking side light with strongly impasted brushstrokes that give solidity of mass and clarity of form.”(13) Sargent was well on his way to developing his mature style.(14)

In 1883, Sargent moved into a new studio in Paris and began his portrait painting practice in earnest. He began attracting a new clientele, that of Paris’ social elite, and was becoming known as a portraitist of women. Sargent’s best known portrait, "Madame X" (1883-4, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was created at this time.(15) Madame Gautreau (1859-1915) was an American socialite living in Paris. She was beautiful, liked striking attitudes with those around her, and stealing the limelight. Many artists had painted her portrait, but none had quite captured her properly on canvas. After much convincing, she allowed Sargent to paint her portrait, and the artist became obsessed. No other sitter had so many studies, nor did they have so much time devoted to them as Sargent devoted to Madame Gautreau.

"Madame X" is a full length profile portrait with the figure in front of a non-descript background. She wears a long black evening gown of satin and velvet with a cuirass bodice and carries a black fan. Her right hand rests on a mahogany table. Her hair is pulled back off of her face and her skin has an unusual, unnatural pallor. The most shocking aspect was the fact that the right shoulder strap was slipped off her right shoulder, an indication of shocking impropriety. The painting caused a stir when exhibited and Madame Gautreau was horrified by the depiction.(16) Sargent, hoping to recover his own reputation, reworked the painting by placing the strap on her shoulder. He changed the name of the painting to "Madame X," but the damage was already done. He removed the painting from the exhibition, and it remained in his studio until it was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art a short time later.

Art historians Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray explain that "Madame X" was a challenge to the boundaries of critical and public taste. It was also an indication of Sargent’s academic ambition and of his nerve. The entire energy of the picture concentrated on the figure, and the fact that the sitter looks to the side and refuses to confront the viewer makes the work that much more intriguing. It added to the mystery and aura that surrounded Madame Gautreau.

The "Madame X" scandal confirmed Sargent’s decision to relocate to London. Having considered the move since 1882, it seemed appropriate to leave Paris until things began to calm down. Although he had moved to London, Sargent remained in tune with French artistic developments. He met both Rodin and Claude Monet while working in Paris, and went through a brief Impressionist period in the latter part of the decade. There is an anecdote of Monet’s that suggests Sargent found genuine Impressionism incomprehensible. When he came to Giverny to paint with Monet, the Impressionist said, “I gave him my colors and he wanted black, and I told him, ‘But I haven’t any.’ ‘Then I can’t paint!’ he cried, and added ‘How do you do it!’”(17) One needs black in order to model form, and Sargent needed black in order to paint.

While Paris and London were Sargent’s principle battleground for his works, he also marketed himself in New York and Boston. In 1887, Sargent received an offer to work in the United States. It came at a perfect moment, as he was not receiving many commissions after his move to London. Sargent had painted several Americans in Paris as well, so a base was established by the time he arrived stateside. Sargent was surprised to find that upon his arrival, he was somewhat of a celebrity. People made a big to-do over him, and threw lavish parties in his honor. He had made his name in Paris, and “had an aura of a returning hero who was not too proud to deploy his skills in his native country.”(18) Sargent brought with him the latest fashions in portraiture and was able to instill his sitters with glamour that no one else could match.

Sargent initially began work in Boston, painting famous socialists such as Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). Gardner set out to amass one of the greatest private art collections in America, most of which is now housed in the museum in Boston. In Sargent’s full-length portrait, Gardner wears a plain black dress with a jeweled belt and matching necklace and earrings. Her hair is pulled away from her face and she gazes serenely at the viewer. The backdrop is an Italian velvet cloth with ornate design that forms a halo around her head. Novelist Henry James described the portrait as “a Byzantine Madonna with a halo.” (19) After an exhibition in Boston and an article in a newly issued illustrated art magazine, Sargent felt that he was established enough to take on New York.

Once in New York, Sargent began attracting the patronage of big business. This was the time of oil, steel, and finance, and Sargent worked for a large number of wealthy families. For example, "Alice Vanderbilt Shepard" (1888, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas) is a striking portrait of the daughter of Elliott Finch Shepard and Margaret Vanderbilt.(20) In the painting, Sargent brings the figure forward from a dark background, and highlights her face, giving her a mysterious appearance.

In late spring of 1888, Sargent returned to England for a short time. He focused on landscape painting, portraits of family and friends, and began experimenting with his style once again. (1888 and 1889 seemed to be a short pause in his career, while he visited with family and traveled with friends.(21) ) By December of 1889, Sargent had returned to the United States and began focusing on portraits once more.

By the early 1890s, Sargent had returned to Britain and began painting the English elite once again. His success as a portraitist in Britain coincided with a renaissance in the art of British portraiture. The avant-garde rescued portraiture from artistic oblivion and breathed new life into it. British society adopted Sargent as one of their own, and the new elite were attracted to his painting style.

One of the apparent changes in Sargent’s work is that he began to paint more men. Up until the 1890s, the artist was primarily known as a painter of women. He often painted gentlemen in official roles or uniform in accordance with traditional imagery – he painted lawyers, politicians, military men, and academians. Interestingly enough, a significant portion of his male portraits were official commissions and represented the decisions of committees rather than the choice of individuals.(22) Furthermore, Sargent’s portraits of women began to change as well. More often, women were represented without their fashionable dress and accessories, and instead depicted as serious career women dedicated to their work. However, Sargent continued to paint society portraits as well.

In 1891, Sargent was commissioned to paint murals at the Boston Public Library. The American Renaissance had begun in the United States and there was an attempt to appropriate the classical European past as a refined backdrop for the economic elite of Boston, New York, and other eastern cities. Unfortunately, the movement did not last very long, but it was enough for Sargent to be able to focus his attention on a different style of painting and subject matter.

For the Boston murals, Sargent decided to paint “The History of Religion,” and traveled extensively in Egypt, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Athens in order to make sketches and prepare for his commission. The murals had to have a sharper focus than his previous paintings and he returned to his drawing instructions from his time at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Amazingly, despite the mural commission and painting portraits while in America, the artist continued to travel back and forth to Europe and take on more clients.

Sargent became increasingly busy during the latter half of the 1890s and averaged fourteen paintings a year. The works represented a wide cross section of British and American society and, due to the number of commissions, the artist was no longer able to treat each one as a new challenge, and thus the works became formulaic. What is remarkable, according to Ormond and Kilmurray, is that Sargent was able to transcend this quality and get to the heart of a life and personality of a sitter.

By 1900, Sargent’s position as a premier portrait painter was assured. However, opinions on the artist’s work were divided. Some praised him as a modern Old Master, while others believed him to be a gifted technician who lacked the imagination and instincts of a true artist. With this criticism, Sargent realized that he had to continue to be inventive if his success was to continue. And with increasing age, the artist certainly began to question what it was he wanted to accomplish as an artist in his later years.

According to Ormand and Kilmurray, the new century brought a change of Sargent’s clientele from the high bourgeoisie to the aristocracy. As a result, Sargent had to modify his style. His public and critical acclaim of the 1890s attracted aristocratic patrons who expected their images to pronounce their noble lineage and affirm their position in society. In turn, Sargent reconstructs the forms of grand manner portraiture for a twentieth-century audience.

Notable changes in his portraits included incorporating more objects and props that served to remind the viewer of the sitter’s social status. Figures became taller and more imposing than their earlier counterparts, costumes became more splendid and referential, and the settings were grander and more abstract. Sargent also borrowed poses of formats from Titian, Raphael, and Sir Joshua Reynolds.(23) For example, "Countess of Lathom"’s (1904, Chrysler Museum) pose of a woman sitting in a majestic throne-like chair, borrows from Reynolds’ "Sarah Siddons as the Trajic Muse" (1783-4, Huntington Library and Art Gallery), which in turn borrows from Michelangelo’s prophets and sybils from the Sistine Ceiling (1504-08). The Museum’s "Portrait of Mrs. Louis E. Raphael" (c.1900-1905) dates from this period.

In 1903, Sargent returned to the United States to deliver the Christian lunette and frieze for the Boston Public Library and to paint President Roosevelt in Washington. In his latter career, America became increasingly important as Sargent exhibited widely across the country. He exhibited at the Metropolitan, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Worchester Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

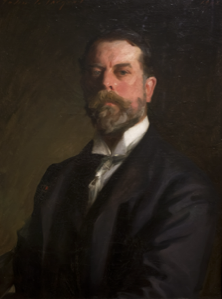

By the middle of the first decade of the twentieth-century, Sargent had tired of portrait painting. In fact, Sargent made a self-portrait in 1907, after which he said, "I have long been sick and tired of portrait painting, and when I was painting my own 'mug,' I firmly decided to devote myself to other brances of art as soon as possible." (24) The artist abandoned portraiture shortly thereafter. Only on rare occasions and with much begging would he paint another portrait. Instead, Sargent focused on landscapes and genre painting. His first pure landscape, "The Mountains of Moab" (1906, Tate Museum) was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1906. He continued to work on the Boston Public Library murals, and returned to the Middle East to get more ideas for the “History of Religion.”

Sargent was in Austrian Tyrol painting when the hostilities of World War I began. Local authorities impounded his paintings and the artist and his colleagues were denied permission to leave for England. They found lodging in a small Austrian town that was filled with troops. The artists were finally issued passports and allowed to return to England. In May of 1918, prime minister Lloyd George formally requested Sargent to travel to the front as an official war artist. As could be expected, this experience had a profound effect on the artist and was one that remained with him the rest of his life. His sketches of the front culminated into a twenty-foot painting entitled "Gassed," depicting soldiers after exposure to poisonous gases. The artist died in London in 1926.

(1) This was required by law if he was to maintain his citizenship.

(2) Sargent’s parents arrived in Liverpool from the United States in 1854. They had lived in Philadelphia where they led a happy life among friends and family. However, with the death of their two year old daughter, Mary’s (Sargent’s mother) health declined and she no longer found joy in their Philadelphia lifestyle. With her spirit broken, Mary told her husband that a trip to Europe might help to heal her broken heart. They never permanently returned to the United States. From Stanley Olson, "John Singer Sargent" (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986): 1-2.

(3) Carter Ratcliff, "John Singer Sargent" (New York: Abbeville Press, 1982): 21.

(4) Sargent’s mother was a watercolorist, and often encouraged her children to paint and draw.

(5) Ibid, 23.

(6) Henry Sargent, upon his return to the United States, painted portraits and genre scenes.

(7) Ratcliff, 35. The Ecole des Beaux-Arts represented the center for academic training, with the curriculum based on the mastery of human form. Mid-century education reforms in Paris brought in an atelier system – whereby young artists served an apprenticeship in the studio of an established painter, learning to draw first from the antique and then from life, before graduating to oil. The atelier system counterbalanced the constricting academic instruction and at its best, gave young artists the benefit of individual and practical tutorials and experience of the realities in life as a working artist. For more, see Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, "John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits," Volume One (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998); Albert Boime, "The Academy and French Painting in the 19th Century" (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986); and "L’Ecole des beaux arts: XIXe et XX siècles" (Paris: L’Harmattan,).

(8) Ormond and Kilmurray, 2.

(9) Ibid.

(10) The painting is "Gloria Mariae Medicis," 1877, and is now in Louvre, Paris.

(11) Ormond and Kilmurray, 5.

(12) Ibid, 57.

(13) Ibid, 69.

(14) This brief biography would not be complete without mentioning Sargent’s "The Daughters of Edward D. Boit" (1882, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Due to space constraint, I only mention here in passing. The painting depicts the four daughters of Sargent’s friend, the American painter Edward Darley Boit. The family lived in Rome, Boston, and Paris, and was well-known in the American communities. The children, however, remained somewhat elusive. The girls are in their Paris apartment: one sits in the foreground with a doll; a second stands at the left of the canvas with her hands folded behind her; while the other two girls stand in the entrance to room – one leans against a giant vase, and the other stands next to her. The two girls are almost hidden in shadow. According to Ormond and Kilmurray, the spatial concept was derived directly from Velazquez’s "Las Meninas," while the restraint and severity recall elements of Sargent’s Venetian studies, in which he had been experimenting with the effects of receding perspectives, shifting focus, oblique light and the atmospheric qualities of dark spaces. It is one of Sargent’s most magnificent canvases. For more, see Ormond and Kilmurray, 66.

(15) There is an unfinished replica dated c. 1884 in the Tate Gallery in London.

(16) Reportedly, Madame Gautreau’s mother chastised Sargent and told him that her daughter hadn’t been able to stop crying since seeing the painting.

(17) Ratcliff, 122.

(18) Ormond and Kilmurray, 195.

(19) Ibid, 210.

(20) Family patriarch Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1977) initially made his money in the steamship business and trade. The Vanderbilts became great patrons and philanthropists.

(21) In the spring of 1889, Sargent worked with Monet and secured funds to purchase Manet’s "Olympia" for the French National Museums. Sargent himself donated 1,000 francs to the project.

(22) Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, "John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the 1890s," Volume II (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002): 5.

(23) Ormond and Kilmurray also identified poses borrowed from Hans Holbein, Sir Anthony Van Dyck, and Thomas Gainsborough.

(24) Frederick w. Coburn, 'The Sargent Decorations in the Boston Public Library,' "American Magazine of Art' 14, no. 1 (January 1923), p. 136, quoted in Ratcliffe, "John Singer Sargent."

- Letha Clair Robertson, 2/19/04

Image credit: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Self-Portrait, 1906, oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Tuscany, Italy, Photograph courtesy of Bridgeman Images, SCP50053

American

(Florence, Italy, 1856 - 1925, London, England)

The life and career of John Singer Sargent present an interesting dichotomy in the history of American art. Born in Italy to American parents, Sargent was an American citizen although he did not set foot in the United States until he was twenty years old.(1) All of his life Sargent lacked stable roots and a place to call home.(2) He was raised speaking English, became fluent in Italian and French and he had a rudimentary knowledge of German. His early nomadic life later reflected his artistic career, for Sargent has never been successfully categorized with one group of artists within the nineteenth or twentieth centuries. Best known for his portraits of affluent aristocrats, Sargent’s work demonstrates a synthesis of nineteenth-century British, French, and American painting. It recalls many styles and periods, but is undoubtedly his own.

Born in Florence, Italy in January 1856, John Singer Sargent was raised in an Anglo-American community. His childhood friend, Vernon Lee, recalled that they played in the garden of Maison Virello, where Dr. and Mrs. Sargent had rented a flat, and in the much larger garden of the nearby Maison Corinaldi. These playgrounds were on the outskirts of the city, an area of palm trees and fig orchards, dwarf rose bushes and empty villas.(3) For ten year-old children, the area served as a perfect place to feed their imaginations, and act out make-believe stories and characters. Sometime around the winter of 1868, Vernon Lee and her family moved and she no longer lived next door to the Sargents. However, Mrs. Sargent made sure that Vernon visited frequently, so that the children could spend their afternoons painting.(4) Vernon recalled that she couldn’t remember if Sargent yet had his own box of paints since he often used hers. While she was making mere pictographs, she remembered that Sargent, with “miraculous intuition and dexterity,” made pictures of ships at sea and houses.(5)

Although Sargent’s father often tried to get the artist to devote serious attention to his academic studies, he finally agreed that his son did have an eye for recording nature. Sargent was always attracted to what he could see, not fantasy or imagination. Artistic productivity ran in the Sargent family – the artist’s grandfather was portrayed by John Singleton Copley, "Epes Sargent" (c. 1760, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.) and another descendent, Henry Sargent, studied with American expatriate Benjamin West in his London studio.(6) Sargent’s father, who had a successful medical practice, decided not to stand in the way of his son’s artistic career. In 1874, the family traveled to Paris, for it was the place to be for any aspiring artist.

When the Sargents arrived in Paris, they had missed the first Impressionist exhibit by one day. The years immediately following Sargent’s arrival in France saw the deaths of Camille Corot and Jean-Francis Millet in 1875, and the death of Gustave Courbet in 1877. Paris was teeming with artistic styles such as Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism – all of which worked their way into Sargent’s art. Meanwhile, with the family settled in a hotel, Dr. Sargent and the young artist set off for the atelier of Carolus-Duran.(7)

Sargent had heard of Carolus-Duran through Walter Launt Palmer, who he had sketched with as a youth in Florence. Carolus-Duran specialized in portraiture, “developing a blend of painterly lines and realism with a distinctive and accessible stamp.”(8) Furthermore, Sargent was attracted to Carolus-Duran’s atelier because of its small size, by what Sargent described as the more “gentlemanly” type of students there, and by the degree of personal attention Carolus-Duran gave to his students. Another point was the high ratio of British and American students

Carolus-Duran worked and taught "au premier coup," meaning at the first touch. This means that forms are built on the canvas rapidly without any reworking. The method demanded faithful visual representation, sophisticated and subtle tonal control with fluid and confident handling. Further, the student was never allowed to brush one surface over the other, he must make a tone for each step of a gradation.(9) This method was at odds with academic training, which laid emphasis on carefully controlled contours with smooth and finished picture surfaces.

Sargent quickly gained attention as his skill impressed itself upon his teachers and colleagues. Carolus-Duran was so confident in Sargent’s work that in 1877, when commissioned to paint a large oil for a ceiling in the Palais dux Luxembourg, he enlisted Sargent and another student to help.(10) It was Sargent’s first experience with a government sponsored project with a grand historical theme, which in nineteenth-century Paris was still the highest form of art. In a sign of mutual respect, Carolus-Duran and Sargent painted portraits of one another within the painting. Two years later, Sargent painted a portrait of Carolus-Duran (1879, Sterling and Francis Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA) which served not only as a declaration of independence from his master and marked the end of his apprenticeship, but also ushered in another phase of his education that took him away from Paris.

The early 1880s were pivotal years for Sargent. Highlighted by two important trips, first to Spain and then to Venice, Sargent saw the works of the Spanish masters for the first time. After visiting Spain, Sargent’s work went from being derivative and stifled to more confident, inventive, and charged with creativity. He copied several of Velazquez’s works, including "Las Meninas" (1656, Museo del Prado, Madrid). One of Sargent’s best known works, "El Jaleo" (1882, Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston) was created under the influence of the Spanish Masters. Recalling Velazquez and El Greco, the painting is a depiction of a Spanish dancer in front of musicians, presumably on stage as it is atypically lit from below. Sargent’s also painted the striking portrait of "Dr. Pozzi (Dr. Pozzi at Home)" (1881, UCLA at the Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Cultural Center, Los Angeles) during this period.

Samuel Jean Pozzi (1846-1918) was a French doctor who was killed by a former patient in his drawing room. In the painting, he wears a red dressing gown and white shirt with a finely pleated collar and stands in front of a red draped background. The background, Pozzi’s pose and the tonality are overt references to both Van Dyck and Velazquez, however, Sargent turns tradition on its ear by “subverting a dark, Spanish gravity to a theatrical characterization of a modern society aesthete in a dazzling red on red 'tour de force'.” (11) While today considered one of Sargent’s masterpieces, the work was not well received upon exhibition. Critics thought it was “gaudy, common, unbearable, unharmonious, and untonal.” (12) It would not be the last time Sargent shocked his audience.

The early 1880s also proved to be an experimental time for the artist. He painted numerous portraits of his family and friends, which represent experiments in characterization and technique. Heads loom out of dark backgrounds, with a conscious effect of mystery. Figures are “modeled in a raking side light with strongly impasted brushstrokes that give solidity of mass and clarity of form.”(13) Sargent was well on his way to developing his mature style.(14)

In 1883, Sargent moved into a new studio in Paris and began his portrait painting practice in earnest. He began attracting a new clientele, that of Paris’ social elite, and was becoming known as a portraitist of women. Sargent’s best known portrait, "Madame X" (1883-4, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was created at this time.(15) Madame Gautreau (1859-1915) was an American socialite living in Paris. She was beautiful, liked striking attitudes with those around her, and stealing the limelight. Many artists had painted her portrait, but none had quite captured her properly on canvas. After much convincing, she allowed Sargent to paint her portrait, and the artist became obsessed. No other sitter had so many studies, nor did they have so much time devoted to them as Sargent devoted to Madame Gautreau.

"Madame X" is a full length profile portrait with the figure in front of a non-descript background. She wears a long black evening gown of satin and velvet with a cuirass bodice and carries a black fan. Her right hand rests on a mahogany table. Her hair is pulled back off of her face and her skin has an unusual, unnatural pallor. The most shocking aspect was the fact that the right shoulder strap was slipped off her right shoulder, an indication of shocking impropriety. The painting caused a stir when exhibited and Madame Gautreau was horrified by the depiction.(16) Sargent, hoping to recover his own reputation, reworked the painting by placing the strap on her shoulder. He changed the name of the painting to "Madame X," but the damage was already done. He removed the painting from the exhibition, and it remained in his studio until it was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art a short time later.

Art historians Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray explain that "Madame X" was a challenge to the boundaries of critical and public taste. It was also an indication of Sargent’s academic ambition and of his nerve. The entire energy of the picture concentrated on the figure, and the fact that the sitter looks to the side and refuses to confront the viewer makes the work that much more intriguing. It added to the mystery and aura that surrounded Madame Gautreau.

The "Madame X" scandal confirmed Sargent’s decision to relocate to London. Having considered the move since 1882, it seemed appropriate to leave Paris until things began to calm down. Although he had moved to London, Sargent remained in tune with French artistic developments. He met both Rodin and Claude Monet while working in Paris, and went through a brief Impressionist period in the latter part of the decade. There is an anecdote of Monet’s that suggests Sargent found genuine Impressionism incomprehensible. When he came to Giverny to paint with Monet, the Impressionist said, “I gave him my colors and he wanted black, and I told him, ‘But I haven’t any.’ ‘Then I can’t paint!’ he cried, and added ‘How do you do it!’”(17) One needs black in order to model form, and Sargent needed black in order to paint.

While Paris and London were Sargent’s principle battleground for his works, he also marketed himself in New York and Boston. In 1887, Sargent received an offer to work in the United States. It came at a perfect moment, as he was not receiving many commissions after his move to London. Sargent had painted several Americans in Paris as well, so a base was established by the time he arrived stateside. Sargent was surprised to find that upon his arrival, he was somewhat of a celebrity. People made a big to-do over him, and threw lavish parties in his honor. He had made his name in Paris, and “had an aura of a returning hero who was not too proud to deploy his skills in his native country.”(18) Sargent brought with him the latest fashions in portraiture and was able to instill his sitters with glamour that no one else could match.

Sargent initially began work in Boston, painting famous socialists such as Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). Gardner set out to amass one of the greatest private art collections in America, most of which is now housed in the museum in Boston. In Sargent’s full-length portrait, Gardner wears a plain black dress with a jeweled belt and matching necklace and earrings. Her hair is pulled away from her face and she gazes serenely at the viewer. The backdrop is an Italian velvet cloth with ornate design that forms a halo around her head. Novelist Henry James described the portrait as “a Byzantine Madonna with a halo.” (19) After an exhibition in Boston and an article in a newly issued illustrated art magazine, Sargent felt that he was established enough to take on New York.

Once in New York, Sargent began attracting the patronage of big business. This was the time of oil, steel, and finance, and Sargent worked for a large number of wealthy families. For example, "Alice Vanderbilt Shepard" (1888, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas) is a striking portrait of the daughter of Elliott Finch Shepard and Margaret Vanderbilt.(20) In the painting, Sargent brings the figure forward from a dark background, and highlights her face, giving her a mysterious appearance.

In late spring of 1888, Sargent returned to England for a short time. He focused on landscape painting, portraits of family and friends, and began experimenting with his style once again. (1888 and 1889 seemed to be a short pause in his career, while he visited with family and traveled with friends.(21) ) By December of 1889, Sargent had returned to the United States and began focusing on portraits once more.

By the early 1890s, Sargent had returned to Britain and began painting the English elite once again. His success as a portraitist in Britain coincided with a renaissance in the art of British portraiture. The avant-garde rescued portraiture from artistic oblivion and breathed new life into it. British society adopted Sargent as one of their own, and the new elite were attracted to his painting style.

One of the apparent changes in Sargent’s work is that he began to paint more men. Up until the 1890s, the artist was primarily known as a painter of women. He often painted gentlemen in official roles or uniform in accordance with traditional imagery – he painted lawyers, politicians, military men, and academians. Interestingly enough, a significant portion of his male portraits were official commissions and represented the decisions of committees rather than the choice of individuals.(22) Furthermore, Sargent’s portraits of women began to change as well. More often, women were represented without their fashionable dress and accessories, and instead depicted as serious career women dedicated to their work. However, Sargent continued to paint society portraits as well.

In 1891, Sargent was commissioned to paint murals at the Boston Public Library. The American Renaissance had begun in the United States and there was an attempt to appropriate the classical European past as a refined backdrop for the economic elite of Boston, New York, and other eastern cities. Unfortunately, the movement did not last very long, but it was enough for Sargent to be able to focus his attention on a different style of painting and subject matter.

For the Boston murals, Sargent decided to paint “The History of Religion,” and traveled extensively in Egypt, Jerusalem, Constantinople, and Athens in order to make sketches and prepare for his commission. The murals had to have a sharper focus than his previous paintings and he returned to his drawing instructions from his time at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Amazingly, despite the mural commission and painting portraits while in America, the artist continued to travel back and forth to Europe and take on more clients.

Sargent became increasingly busy during the latter half of the 1890s and averaged fourteen paintings a year. The works represented a wide cross section of British and American society and, due to the number of commissions, the artist was no longer able to treat each one as a new challenge, and thus the works became formulaic. What is remarkable, according to Ormond and Kilmurray, is that Sargent was able to transcend this quality and get to the heart of a life and personality of a sitter.

By 1900, Sargent’s position as a premier portrait painter was assured. However, opinions on the artist’s work were divided. Some praised him as a modern Old Master, while others believed him to be a gifted technician who lacked the imagination and instincts of a true artist. With this criticism, Sargent realized that he had to continue to be inventive if his success was to continue. And with increasing age, the artist certainly began to question what it was he wanted to accomplish as an artist in his later years.

According to Ormand and Kilmurray, the new century brought a change of Sargent’s clientele from the high bourgeoisie to the aristocracy. As a result, Sargent had to modify his style. His public and critical acclaim of the 1890s attracted aristocratic patrons who expected their images to pronounce their noble lineage and affirm their position in society. In turn, Sargent reconstructs the forms of grand manner portraiture for a twentieth-century audience.

Notable changes in his portraits included incorporating more objects and props that served to remind the viewer of the sitter’s social status. Figures became taller and more imposing than their earlier counterparts, costumes became more splendid and referential, and the settings were grander and more abstract. Sargent also borrowed poses of formats from Titian, Raphael, and Sir Joshua Reynolds.(23) For example, "Countess of Lathom"’s (1904, Chrysler Museum) pose of a woman sitting in a majestic throne-like chair, borrows from Reynolds’ "Sarah Siddons as the Trajic Muse" (1783-4, Huntington Library and Art Gallery), which in turn borrows from Michelangelo’s prophets and sybils from the Sistine Ceiling (1504-08). The Museum’s "Portrait of Mrs. Louis E. Raphael" (c.1900-1905) dates from this period.

In 1903, Sargent returned to the United States to deliver the Christian lunette and frieze for the Boston Public Library and to paint President Roosevelt in Washington. In his latter career, America became increasingly important as Sargent exhibited widely across the country. He exhibited at the Metropolitan, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Worchester Museum of Art, and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By the middle of the first decade of the twentieth-century, Sargent had tired of portrait painting. In fact, Sargent made a self-portrait in 1907, after which he said, "I have long been sick and tired of portrait painting, and when I was painting my own 'mug,' I firmly decided to devote myself to other brances of art as soon as possible." (24) The artist abandoned portraiture shortly thereafter. Only on rare occasions and with much begging would he paint another portrait. Instead, Sargent focused on landscapes and genre painting. His first pure landscape, "The Mountains of Moab" (1906, Tate Museum) was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1906. He continued to work on the Boston Public Library murals, and returned to the Middle East to get more ideas for the “History of Religion.”

Sargent was in Austrian Tyrol painting when the hostilities of World War I began. Local authorities impounded his paintings and the artist and his colleagues were denied permission to leave for England. They found lodging in a small Austrian town that was filled with troops. The artists were finally issued passports and allowed to return to England. In May of 1918, prime minister Lloyd George formally requested Sargent to travel to the front as an official war artist. As could be expected, this experience had a profound effect on the artist and was one that remained with him the rest of his life. His sketches of the front culminated into a twenty-foot painting entitled "Gassed," depicting soldiers after exposure to poisonous gases. The artist died in London in 1926.

(1) This was required by law if he was to maintain his citizenship.

(2) Sargent’s parents arrived in Liverpool from the United States in 1854. They had lived in Philadelphia where they led a happy life among friends and family. However, with the death of their two year old daughter, Mary’s (Sargent’s mother) health declined and she no longer found joy in their Philadelphia lifestyle. With her spirit broken, Mary told her husband that a trip to Europe might help to heal her broken heart. They never permanently returned to the United States. From Stanley Olson, "John Singer Sargent" (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986): 1-2.

(3) Carter Ratcliff, "John Singer Sargent" (New York: Abbeville Press, 1982): 21.

(4) Sargent’s mother was a watercolorist, and often encouraged her children to paint and draw.

(5) Ibid, 23.

(6) Henry Sargent, upon his return to the United States, painted portraits and genre scenes.

(7) Ratcliff, 35. The Ecole des Beaux-Arts represented the center for academic training, with the curriculum based on the mastery of human form. Mid-century education reforms in Paris brought in an atelier system – whereby young artists served an apprenticeship in the studio of an established painter, learning to draw first from the antique and then from life, before graduating to oil. The atelier system counterbalanced the constricting academic instruction and at its best, gave young artists the benefit of individual and practical tutorials and experience of the realities in life as a working artist. For more, see Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, "John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits," Volume One (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998); Albert Boime, "The Academy and French Painting in the 19th Century" (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986); and "L’Ecole des beaux arts: XIXe et XX siècles" (Paris: L’Harmattan,).

(8) Ormond and Kilmurray, 2.

(9) Ibid.

(10) The painting is "Gloria Mariae Medicis," 1877, and is now in Louvre, Paris.

(11) Ormond and Kilmurray, 5.

(12) Ibid, 57.

(13) Ibid, 69.

(14) This brief biography would not be complete without mentioning Sargent’s "The Daughters of Edward D. Boit" (1882, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Due to space constraint, I only mention here in passing. The painting depicts the four daughters of Sargent’s friend, the American painter Edward Darley Boit. The family lived in Rome, Boston, and Paris, and was well-known in the American communities. The children, however, remained somewhat elusive. The girls are in their Paris apartment: one sits in the foreground with a doll; a second stands at the left of the canvas with her hands folded behind her; while the other two girls stand in the entrance to room – one leans against a giant vase, and the other stands next to her. The two girls are almost hidden in shadow. According to Ormond and Kilmurray, the spatial concept was derived directly from Velazquez’s "Las Meninas," while the restraint and severity recall elements of Sargent’s Venetian studies, in which he had been experimenting with the effects of receding perspectives, shifting focus, oblique light and the atmospheric qualities of dark spaces. It is one of Sargent’s most magnificent canvases. For more, see Ormond and Kilmurray, 66.

(15) There is an unfinished replica dated c. 1884 in the Tate Gallery in London.

(16) Reportedly, Madame Gautreau’s mother chastised Sargent and told him that her daughter hadn’t been able to stop crying since seeing the painting.

(17) Ratcliff, 122.

(18) Ormond and Kilmurray, 195.

(19) Ibid, 210.

(20) Family patriarch Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1977) initially made his money in the steamship business and trade. The Vanderbilts became great patrons and philanthropists.

(21) In the spring of 1889, Sargent worked with Monet and secured funds to purchase Manet’s "Olympia" for the French National Museums. Sargent himself donated 1,000 francs to the project.

(22) Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, "John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the 1890s," Volume II (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002): 5.

(23) Ormond and Kilmurray also identified poses borrowed from Hans Holbein, Sir Anthony Van Dyck, and Thomas Gainsborough.

(24) Frederick w. Coburn, 'The Sargent Decorations in the Boston Public Library,' "American Magazine of Art' 14, no. 1 (January 1923), p. 136, quoted in Ratcliffe, "John Singer Sargent."

- Letha Clair Robertson, 2/19/04

Image credit: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), Self-Portrait, 1906, oil on canvas, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Tuscany, Italy, Photograph courtesy of Bridgeman Images, SCP50053

Artist Objects