Georgia O'Keeffe

American

(Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, 1887 – 1986, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

Throughout her life, Georgia O’Keeffe contended that she was not a woman, but an artist. Her prolific career spanned over six decades and she created more than nine hundred works. Born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887, O’Keeffe was the second child to be born to Ida and Francis O’Keeffe. The family lived in a rural part of the country, which at the time of O’Keeffe’s birth had yet to be tamed—United States troops had still to engage in the last Great Indian war. Ida, Georgia’s mother, regularly read to her children, particularly Longfellow, and stories about pioneers, cowboys, and Indians—stories which were usually set in New Mexico and Texas. These stories instilled in the artist a need to travel west, where O’Keeffe would create her best known paintings.

O’Keeffe later remembered that as a child, she spent much of her time alone, and her parents were at first unaware of her artistic talent. From 1901 to approximately 1907, O’Keeffe bounced around a number of schools for unknown reasons. She attended the Sacred Heart Academy of Art in 1901, an exclusive convent boarding school on the outskirts of Madison, Wisconsin. For unknown reasons, a year later, she was removed from the school and her sisters Anita and Ida were enrolled instead. She was then sent with her brother Francis to live with an aunt in Madison. At a local high school, O’Keeffe began her first paintings of flowers, creating a series of jack-in-the-pulpits. When school finished in 1903, O’Keeffe left Wisconsin to joint the rest of her family in “Wheatland,” the new Williamsburg home.(1)

The following school year, O’Keeffe was sent to Chatham Episcopal Institute, a private school nearly two hundred miles away from her family. The artist’s talents were noticed by her teacher and school principal, Elizabeth May Willis, and were encouraged. O’Keeffe enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905 and was there a year. Upon visiting her family in Virginia at the end of the school year, the artist caught typhoid fever, and did not return to Chicago. Instead, O’Keeffe enrolled in the Art Student’s League in New York the following year where she studied with William Merritt Chase.(2) Chase’s influence on O’Keeffe is evident in an early painting entitled "Rabbit and Copper Pot" (1907, unlocated) which won her the Chase scholarship and the opportunity to study at the League’s summer school at Lake George in upstate New York.

During the winter of 1907-1908, O’Keeffe visited the 291 Gallery for the first time. 291 was operated by photographer Alfred Stieglitz, a champion for modern art in America.(3) O’Keeffe and a group of students went to the gallery to see a group of Rodin’s drawings, which did not impress her. Little did she know it would be her works that hung on those same walls a short nine years later.

One of the most influential people of O’Keeffe’s early career was Alan Bement, whom she studied with at the University of Virginia. Bement had studied with Arthur Wesley Dow, whose books "Composition and The Theory" and "Practice of Teaching Art" laid out the underlying aesthetics in painting and principles of abstraction. Furthermore, O’Keeffe was introduced to Wassily Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which also explained the principles of abstraction. By 1912, O’Keeffe was teaching art in Amarillo, Texas, and it was here that she began her first abstractions.

Amarillo, in 1912, was still cattle country. Oil and gas had yet to be pumped, and Amarillo was just a rowdy little frontier town that was made up of merchants, lawyers, cowhands, and saloon girls. O’Keeffe relished in the fact that she was living and working in the place that she had come to love through her mother’s readings. It was also in Amarillo that O’Keeffe was exposed to the vastness of space and the solitude that she would come to adore in New Mexico. Amarillo was nothing but vast space—for the plains and the sky stretched as far as the eye could see in a never-ending race to the horizon. By the end of 1914, however, O’Keeffe had resigned her teaching position and returned to New York in order to study with Dow at the Teacher’s College at Columbia University.

Dow had studied with Gauguin and other Post-Impressionists, and was a great collector of Japanese prints, whose flattened forms he greatly admired. He was open-minded and had a greater tolerance for experimentation than many of her former teachers. She became increasingly impressed with Dow since she had neither studied abroad not been subject to many European influences.

At this time, O’Keeffe’s work, such as "Drawing XIII" (1915, Metropolitan Museum of Art) were abstractions in black and white. The works were experimentations with line, characterized by a meshing of sharp, jagged edges and morphic forms. O’Keeffe was searching for her own voice and decided that by working solely in black and white, she could free herself completely of former influences. She decided to work in black and white until she had examined all her potentials and until she exhausted all possibilities.

While in New York, O’Keeffe befriended Anita Pollitzer, who was the catalyst between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz. O’Keeffe had frequented 291, viewing works by artist such as Braque and Picasso, yet she still remained intimidated by Stieglitz. In 1915, O’Keeffe accepted a teaching job in South Carolina and gradually became absorbed in her own painting. She spent much of her time outdoors, walking the foothills of the Appalachians, and she began to wrestle with the question of whether to paint for herself or others.

In 1916, O’Keeffe sent a group of black and white charcoal drawings to Pollitzer. Pollitzer later said, “I was struck by their aliveness. They were different…These drawings were saying something that had not yet been said.”(4) Knowing that O’Keeffe was sensitive about who saw her works, Pollitzer bravely took the drawings to Stieglitz. Upon studying the works, Stieglitz declared: “At last, a woman on paper,” and added that he would not mind showing the drawings in the gallery.(5) And thus began a somewhat tumultuous relationship between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz that would last the rest of their lives.

Initially, O’Keeffe was infuriated that the works were shown without her permission, and without even getting her name correct—Stieglitz exhibited them as “Virginia O’Keeffe.” The artist rushed to 291, prepared for an angry confrontation. Stieglitz was gone on jury duty, and when the two did finally meet, Stieglitz explained that he found the drawings so wonderful he had to exhibit them and wanted to see more. The works caused a stir in New York, as many were shocked by the “sexuality” of what they saw. Stieglitz himself helped to foster the idea, although throughout her life, O’Keeffe proclaimed there was nothing intentionally sexual about her work, and could not understand how others saw it as such. One cannot help but wonder if Stieglitz did not engineer the discussion in order to bring attention to the young O’Keeffe.

Soon after, O’Keeffe once again returned to Texas, this time accepting a teaching position at West Texas State Normal College in Canyon. While in Texas, she continued to correspond with Stieglitz, and he began showing her work alongside Arthur Dove, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley. From then on, she would be considered a part of Stieglitz’s inner circle.

O’Keeffe, having commenced working in color once again, created one of her best known early series of this period. "Evening Star" (1916, Yale University Art Gallery) is an explosion of color representing her interpretation of light and the evening sky in Canyon, Texas. She recalled years later, that as she walked out onto the West Texas plains, “The evening star would be high in the sunset sky when it was still broad daylight. That evening star fascinated me…I had nothing to do but walk into nowhere and the wide sunset space with the star.”(6) This stunning series of paintings celebrated the vibrant energy that emerged from that star. In the watercolors, the star is represented by a yellow orb, while colors radiate around it and across the paper. They show a contrasting technique of loose handling and control at the same time. It was also during this time that the artist made her first visit to Santa Fe, New Mexico with her sister and friends. “I loved it immediately,” O’Keeffe later recalled, “from then on I was always trying to get back.”(7)

By 1919, O’Keeffe had returned to New York and moved in with Stieglitz. She began painting full time, and the couple spent their time between New York City and Stieglitz’s home at Lake George. There, O’Keeffe was able to enjoy a long period of solitude and time in which to paint, predominantly in oils. Her work of this period reflected her happiness, and the couple began to tackle the same subject matter—New York City at night. Stieglitz continued with his own work, and also continued to market, exhibit and sell O’Keeffe’s along with other artists he considered his “children.” It was during this period that O’Keeffe began her well-known flower paintings, such as "Light Iris" (1924, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and "Poppy" (1927, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida). Her flower paintings were often painted frontally, “rather like butterflies pinned down for scrutiny: lilies, petunias, jack-in-the-pulpits, poppies, and irises were only a few of the specimens which O’Keeffe worked on in over two hundred flower paintings.”(8)

In the late spring of 1929, O’Keeffe, along with Beck Strand (photographer Paul Strand’s wife), left New York to visit New Mexico. Upon their arrival in Santa Fe, they were met by Mabel Dodge Luhan, who insisted they visit her at home in Taos, an artists’ colony seventy miles to the north of San Felipe.(9) While there, O’Keeffe was loaned an adobe studio with large windows where she painted. She could look out over the meadows to the sagebrush and beyond to the Taos mountains. The New Mexico landscape provided her inspiration for the paintings she is best known.

Wanting to explore the landscape further, O’Keeffe bought a black Model A Ford, which she eventually converted into a mobile studio. During her explorations, she often came across heavy, primitive crosses. The locals told her that these were the crosses of Penitente, a secret religious society that had originated in medieval Spain, which practiced flagellations and staged mock crucifixions. O’Keeffe painted a series of paintings depicting the black crosses, and also began a series of paintings based on the theme of the mission church at Ranchos de Taos. O’Keeffe eventually bought a home in Abiquiu, New Mexico, which came to be known as Ghost Ranch. From this point on, she would divide her time between New York and New Mexico, permanently moving to New Mexico after Stieglitz’s death in 1946. She would remain in New Mexico until her own death in 1986.

In addition to architectural studies and floral compositions, O’Keeffe also began painting pure landscapes of New Mexico. Begun initially with her first trip in 1929, the landscapes were treated in a similar way to that of her flower motifs: a single form enlarged to fill the entire picture space. The Museum’s "Hills Before Taos" (1930) is one of these paintings. Another important theme in her later works was the recurring subject of bones that the artist found scattered across the New Mexican landscape. During her summers west, O’Keeffe collected the dry, sun-bleached bones and shipped them to Lake George before her move. "Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue" (1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art), one of her most famous paintings, is a study of a single bone isolated from its natural environment. It was the shape and texture of the bones, with their interplay of positive and negative, convex and concave that inspired the artist to paint them over and over again. The artist eventually combined her three themes, incorporating the skull, flower, and landscape, in works such as "Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses" (1931, Art Institute of Chicago).

O’Keeffe’s later work is predominantly abstractions, in which she further explored architectural elements of her studio, in paintings such as "Wall with Green Door" (1952, Corcoran Gallery) and "White Patio with Red Door" (1960, Regis Collection, Minneapolis). Other later works are abstract representation of nature where the subject is recognizable, such as waterfall paintings of the 1950s and the Grand Canyon paintings from the 1960s.

O’Keeffe continued to paint until 1972, when she lost her central vision. During her lifetime, she wore the mantle of fame uneasily. There was a television documentary, retrospective shows, newspaper and magazine articles, and her work was being reproduced everywhere. Many made pilgrimages to see her: Andy Warhol, Joan Mondale, and even fashion designer Calvin Klein, who arrived to find O’Keeffe wearing a cardigan he had sent as a gift some years before. (Photographs of Klein at O’Keeffe’s home were later used in an ad campaign for his clothing.) Still fiercely protective of her privacy, unwanted visitors were often met with a slammed door and a sharp tongue.(10) As she became increasingly frail in her old age, Juan Hamilton (O’Keefe’s assistant since the mid-1970s) convinced her to move to Santa Fe, where she would be closer to hospital care. Scorning death, O’Keeffe liked to say she would live to be one hundred years old. When she reached her ninetieth birthday, she upped the figure to 125. She said: “When I think of death, I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore, unless the Indians are right and my spirit will walk here after I’m gone.”(11) She died in 1986 at the age of ninety-nine.

1) The O'Keeffes moved from Wisconsin to Virginia in hopes of having better luck financialiy.

2) Chase was attempting to establish art as an “honorable” profession in America. In order to make American art less provincial, Chase taught what he thought were the best European methods and generally encouraged a spirit of innovation, originality, and progress. Chase required his students to create a new painting each day, one on top of the other until it was too overloaded with paint to continue. This rapid method of painting was later credited as part of the reasoning behind O’Keeffe’s prolific creation of works.

3) Having heard the stories about Alfred Stieglitz exhibiting the controversial drawings of Auguste Rodin, the students decided to investigate for themselves. Once they arrived, some deliberately asked questions in order to unleash one of Stieglitz’s famous passionate speeches in defense of avant-garde art. O’Keeffe later recalled that she felt somewhat intimidated by Stieglitz, and consequently withdrew to the back of the room.

4) Maria Constantino, Georgia O’Keeffe (New York: SMITHMARK Publishers, Inc., 1994):18.

5) Ibid.

6) Sharyn R. Udall, O’Keeffe and Texas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998): 45.

7) Constantino, 23.

8) Ibid, 87.

9) Luhan was a New York heiress and collector—of people—and after moving to Taos, she continued her tradition of inviting artists and writers to visit.

10) Legend has it that when one stranger arrived at her gate and asked to see her, she is reported to have said, “Front side!”, then turned around and announced “Back side!”, turned again, said goodbye and slammed the gate on the astonished visitor.

11) Constantino, 52.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 5/20/04

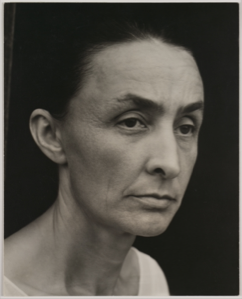

Image credit: Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946), Georgia O’Keeffe, 1932, gelatin silver print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, Gift of Georgia O'Keeffe, through the generosity of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation and Jennifer and Joseph Duke, 1997, 1997.61.36

American

(Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, 1887 – 1986, Santa Fe, New Mexico)

Throughout her life, Georgia O’Keeffe contended that she was not a woman, but an artist. Her prolific career spanned over six decades and she created more than nine hundred works. Born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin in 1887, O’Keeffe was the second child to be born to Ida and Francis O’Keeffe. The family lived in a rural part of the country, which at the time of O’Keeffe’s birth had yet to be tamed—United States troops had still to engage in the last Great Indian war. Ida, Georgia’s mother, regularly read to her children, particularly Longfellow, and stories about pioneers, cowboys, and Indians—stories which were usually set in New Mexico and Texas. These stories instilled in the artist a need to travel west, where O’Keeffe would create her best known paintings.

O’Keeffe later remembered that as a child, she spent much of her time alone, and her parents were at first unaware of her artistic talent. From 1901 to approximately 1907, O’Keeffe bounced around a number of schools for unknown reasons. She attended the Sacred Heart Academy of Art in 1901, an exclusive convent boarding school on the outskirts of Madison, Wisconsin. For unknown reasons, a year later, she was removed from the school and her sisters Anita and Ida were enrolled instead. She was then sent with her brother Francis to live with an aunt in Madison. At a local high school, O’Keeffe began her first paintings of flowers, creating a series of jack-in-the-pulpits. When school finished in 1903, O’Keeffe left Wisconsin to joint the rest of her family in “Wheatland,” the new Williamsburg home.(1)

The following school year, O’Keeffe was sent to Chatham Episcopal Institute, a private school nearly two hundred miles away from her family. The artist’s talents were noticed by her teacher and school principal, Elizabeth May Willis, and were encouraged. O’Keeffe enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1905 and was there a year. Upon visiting her family in Virginia at the end of the school year, the artist caught typhoid fever, and did not return to Chicago. Instead, O’Keeffe enrolled in the Art Student’s League in New York the following year where she studied with William Merritt Chase.(2) Chase’s influence on O’Keeffe is evident in an early painting entitled "Rabbit and Copper Pot" (1907, unlocated) which won her the Chase scholarship and the opportunity to study at the League’s summer school at Lake George in upstate New York.

During the winter of 1907-1908, O’Keeffe visited the 291 Gallery for the first time. 291 was operated by photographer Alfred Stieglitz, a champion for modern art in America.(3) O’Keeffe and a group of students went to the gallery to see a group of Rodin’s drawings, which did not impress her. Little did she know it would be her works that hung on those same walls a short nine years later.

One of the most influential people of O’Keeffe’s early career was Alan Bement, whom she studied with at the University of Virginia. Bement had studied with Arthur Wesley Dow, whose books "Composition and The Theory" and "Practice of Teaching Art" laid out the underlying aesthetics in painting and principles of abstraction. Furthermore, O’Keeffe was introduced to Wassily Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which also explained the principles of abstraction. By 1912, O’Keeffe was teaching art in Amarillo, Texas, and it was here that she began her first abstractions.

Amarillo, in 1912, was still cattle country. Oil and gas had yet to be pumped, and Amarillo was just a rowdy little frontier town that was made up of merchants, lawyers, cowhands, and saloon girls. O’Keeffe relished in the fact that she was living and working in the place that she had come to love through her mother’s readings. It was also in Amarillo that O’Keeffe was exposed to the vastness of space and the solitude that she would come to adore in New Mexico. Amarillo was nothing but vast space—for the plains and the sky stretched as far as the eye could see in a never-ending race to the horizon. By the end of 1914, however, O’Keeffe had resigned her teaching position and returned to New York in order to study with Dow at the Teacher’s College at Columbia University.

Dow had studied with Gauguin and other Post-Impressionists, and was a great collector of Japanese prints, whose flattened forms he greatly admired. He was open-minded and had a greater tolerance for experimentation than many of her former teachers. She became increasingly impressed with Dow since she had neither studied abroad not been subject to many European influences.

At this time, O’Keeffe’s work, such as "Drawing XIII" (1915, Metropolitan Museum of Art) were abstractions in black and white. The works were experimentations with line, characterized by a meshing of sharp, jagged edges and morphic forms. O’Keeffe was searching for her own voice and decided that by working solely in black and white, she could free herself completely of former influences. She decided to work in black and white until she had examined all her potentials and until she exhausted all possibilities.

While in New York, O’Keeffe befriended Anita Pollitzer, who was the catalyst between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz. O’Keeffe had frequented 291, viewing works by artist such as Braque and Picasso, yet she still remained intimidated by Stieglitz. In 1915, O’Keeffe accepted a teaching job in South Carolina and gradually became absorbed in her own painting. She spent much of her time outdoors, walking the foothills of the Appalachians, and she began to wrestle with the question of whether to paint for herself or others.

In 1916, O’Keeffe sent a group of black and white charcoal drawings to Pollitzer. Pollitzer later said, “I was struck by their aliveness. They were different…These drawings were saying something that had not yet been said.”(4) Knowing that O’Keeffe was sensitive about who saw her works, Pollitzer bravely took the drawings to Stieglitz. Upon studying the works, Stieglitz declared: “At last, a woman on paper,” and added that he would not mind showing the drawings in the gallery.(5) And thus began a somewhat tumultuous relationship between O’Keeffe and Stieglitz that would last the rest of their lives.

Initially, O’Keeffe was infuriated that the works were shown without her permission, and without even getting her name correct—Stieglitz exhibited them as “Virginia O’Keeffe.” The artist rushed to 291, prepared for an angry confrontation. Stieglitz was gone on jury duty, and when the two did finally meet, Stieglitz explained that he found the drawings so wonderful he had to exhibit them and wanted to see more. The works caused a stir in New York, as many were shocked by the “sexuality” of what they saw. Stieglitz himself helped to foster the idea, although throughout her life, O’Keeffe proclaimed there was nothing intentionally sexual about her work, and could not understand how others saw it as such. One cannot help but wonder if Stieglitz did not engineer the discussion in order to bring attention to the young O’Keeffe.

Soon after, O’Keeffe once again returned to Texas, this time accepting a teaching position at West Texas State Normal College in Canyon. While in Texas, she continued to correspond with Stieglitz, and he began showing her work alongside Arthur Dove, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley. From then on, she would be considered a part of Stieglitz’s inner circle.

O’Keeffe, having commenced working in color once again, created one of her best known early series of this period. "Evening Star" (1916, Yale University Art Gallery) is an explosion of color representing her interpretation of light and the evening sky in Canyon, Texas. She recalled years later, that as she walked out onto the West Texas plains, “The evening star would be high in the sunset sky when it was still broad daylight. That evening star fascinated me…I had nothing to do but walk into nowhere and the wide sunset space with the star.”(6) This stunning series of paintings celebrated the vibrant energy that emerged from that star. In the watercolors, the star is represented by a yellow orb, while colors radiate around it and across the paper. They show a contrasting technique of loose handling and control at the same time. It was also during this time that the artist made her first visit to Santa Fe, New Mexico with her sister and friends. “I loved it immediately,” O’Keeffe later recalled, “from then on I was always trying to get back.”(7)

By 1919, O’Keeffe had returned to New York and moved in with Stieglitz. She began painting full time, and the couple spent their time between New York City and Stieglitz’s home at Lake George. There, O’Keeffe was able to enjoy a long period of solitude and time in which to paint, predominantly in oils. Her work of this period reflected her happiness, and the couple began to tackle the same subject matter—New York City at night. Stieglitz continued with his own work, and also continued to market, exhibit and sell O’Keeffe’s along with other artists he considered his “children.” It was during this period that O’Keeffe began her well-known flower paintings, such as "Light Iris" (1924, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts) and "Poppy" (1927, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida). Her flower paintings were often painted frontally, “rather like butterflies pinned down for scrutiny: lilies, petunias, jack-in-the-pulpits, poppies, and irises were only a few of the specimens which O’Keeffe worked on in over two hundred flower paintings.”(8)

In the late spring of 1929, O’Keeffe, along with Beck Strand (photographer Paul Strand’s wife), left New York to visit New Mexico. Upon their arrival in Santa Fe, they were met by Mabel Dodge Luhan, who insisted they visit her at home in Taos, an artists’ colony seventy miles to the north of San Felipe.(9) While there, O’Keeffe was loaned an adobe studio with large windows where she painted. She could look out over the meadows to the sagebrush and beyond to the Taos mountains. The New Mexico landscape provided her inspiration for the paintings she is best known.

Wanting to explore the landscape further, O’Keeffe bought a black Model A Ford, which she eventually converted into a mobile studio. During her explorations, she often came across heavy, primitive crosses. The locals told her that these were the crosses of Penitente, a secret religious society that had originated in medieval Spain, which practiced flagellations and staged mock crucifixions. O’Keeffe painted a series of paintings depicting the black crosses, and also began a series of paintings based on the theme of the mission church at Ranchos de Taos. O’Keeffe eventually bought a home in Abiquiu, New Mexico, which came to be known as Ghost Ranch. From this point on, she would divide her time between New York and New Mexico, permanently moving to New Mexico after Stieglitz’s death in 1946. She would remain in New Mexico until her own death in 1986.

In addition to architectural studies and floral compositions, O’Keeffe also began painting pure landscapes of New Mexico. Begun initially with her first trip in 1929, the landscapes were treated in a similar way to that of her flower motifs: a single form enlarged to fill the entire picture space. The Museum’s "Hills Before Taos" (1930) is one of these paintings. Another important theme in her later works was the recurring subject of bones that the artist found scattered across the New Mexican landscape. During her summers west, O’Keeffe collected the dry, sun-bleached bones and shipped them to Lake George before her move. "Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue" (1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art), one of her most famous paintings, is a study of a single bone isolated from its natural environment. It was the shape and texture of the bones, with their interplay of positive and negative, convex and concave that inspired the artist to paint them over and over again. The artist eventually combined her three themes, incorporating the skull, flower, and landscape, in works such as "Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses" (1931, Art Institute of Chicago).

O’Keeffe’s later work is predominantly abstractions, in which she further explored architectural elements of her studio, in paintings such as "Wall with Green Door" (1952, Corcoran Gallery) and "White Patio with Red Door" (1960, Regis Collection, Minneapolis). Other later works are abstract representation of nature where the subject is recognizable, such as waterfall paintings of the 1950s and the Grand Canyon paintings from the 1960s.

O’Keeffe continued to paint until 1972, when she lost her central vision. During her lifetime, she wore the mantle of fame uneasily. There was a television documentary, retrospective shows, newspaper and magazine articles, and her work was being reproduced everywhere. Many made pilgrimages to see her: Andy Warhol, Joan Mondale, and even fashion designer Calvin Klein, who arrived to find O’Keeffe wearing a cardigan he had sent as a gift some years before. (Photographs of Klein at O’Keeffe’s home were later used in an ad campaign for his clothing.) Still fiercely protective of her privacy, unwanted visitors were often met with a slammed door and a sharp tongue.(10) As she became increasingly frail in her old age, Juan Hamilton (O’Keefe’s assistant since the mid-1970s) convinced her to move to Santa Fe, where she would be closer to hospital care. Scorning death, O’Keeffe liked to say she would live to be one hundred years old. When she reached her ninetieth birthday, she upped the figure to 125. She said: “When I think of death, I only regret that I will not be able to see this beautiful country anymore, unless the Indians are right and my spirit will walk here after I’m gone.”(11) She died in 1986 at the age of ninety-nine.

1) The O'Keeffes moved from Wisconsin to Virginia in hopes of having better luck financialiy.

2) Chase was attempting to establish art as an “honorable” profession in America. In order to make American art less provincial, Chase taught what he thought were the best European methods and generally encouraged a spirit of innovation, originality, and progress. Chase required his students to create a new painting each day, one on top of the other until it was too overloaded with paint to continue. This rapid method of painting was later credited as part of the reasoning behind O’Keeffe’s prolific creation of works.

3) Having heard the stories about Alfred Stieglitz exhibiting the controversial drawings of Auguste Rodin, the students decided to investigate for themselves. Once they arrived, some deliberately asked questions in order to unleash one of Stieglitz’s famous passionate speeches in defense of avant-garde art. O’Keeffe later recalled that she felt somewhat intimidated by Stieglitz, and consequently withdrew to the back of the room.

4) Maria Constantino, Georgia O’Keeffe (New York: SMITHMARK Publishers, Inc., 1994):18.

5) Ibid.

6) Sharyn R. Udall, O’Keeffe and Texas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998): 45.

7) Constantino, 23.

8) Ibid, 87.

9) Luhan was a New York heiress and collector—of people—and after moving to Taos, she continued her tradition of inviting artists and writers to visit.

10) Legend has it that when one stranger arrived at her gate and asked to see her, she is reported to have said, “Front side!”, then turned around and announced “Back side!”, turned again, said goodbye and slammed the gate on the astonished visitor.

11) Constantino, 52.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 5/20/04

Image credit: Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946), Georgia O’Keeffe, 1932, gelatin silver print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, Gift of Georgia O'Keeffe, through the generosity of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation and Jennifer and Joseph Duke, 1997, 1997.61.36

Artist Objects