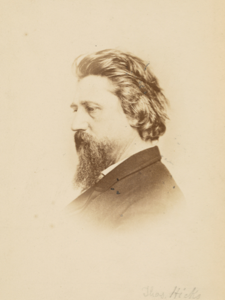

Thomas Hicks

American

(Newtown, Pennsylvania, 1823 - 1890, Trenton Falls, New York)

One of the great absurdities in the discipline of American art history is that modern art historians, examining almost four hundred years of art, can effectively decide what is good, mediocre or bad art. With the stroke of a pen, an artist’s entire career can virtually be eliminated from the history of American art, based on the opinion of a single scholar. Such is the case with American portraitist Thomas Hicks (1823-90). In his own lifetime, Hicks was an extremely well known and affluent portraitist. He and his wife lived next door to the William and Caroline Astor in New York and associated with prominent social circles in the city. For almost twenty-five years, beginning in 1850, Hicks was ranked as one of the most fashionable and prosperous portrait painters in America. In 1866, when Hicks traveled to New Haven, Connecticut to paint copies of John Trumbull’s portrait of "Roger Sherman," the state replied that they were merely graced by the presence of such a great man.(1) Hicks is mentioned in a large number of nineteenth-century journals such as "Harper’s Weekly," "The Century," and "The New England Magazine" as a talented and influential portraitist—after all, he painted the first life portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Chicago Historical Society, 1860). Art historian David Tatham stated that Hicks’ personality contributed to his success—Hicks was said to be “an amusing mimic and a witty raconteur who in his early years in New York preserved something of the genteel bohemianism of his student days in Rome and Paris by wearing his hair in long flowing locks.”(2) Yet, after 1940, his name virtually disappeared from the annals of American art history.

Today, Hicks is most commonly mentioned in passing with his cousin Edward, the primitive painter of the "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings. As Tatham noted, it is incredible that Hicks, who received professional training in Philadelphia, New York, Paris and Rome, took a backseat to his cousin Edward who never received any formal training.(3) Tatham’s article, “Thomas Hicks at Trenton Falls,” is the most thorough examination of Thomas Hicks’ works ever published, and it focuses on his later landscapes and portraits painted at Trenton Falls, New Jersey. Edward has had a large number of books and articles written about his "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings alone. One can’t help but wonder why an artist such as Thomas Hicks, who was so highly respected and revered in his own time, has been lost to modern scholars. As a result, his biography is sketchy at best, but we do know major points and events in his life.

Thomas Hicks was born on October 18, 1823 in Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to Joseph and Jane Hicks. He was raised with seven brothers and sisters. Little is known of his early life until he entered his cousin Edward’s sign and coach making shop sometime around 1836. While apprenticing in Edward’s shop, Hicks executed at least fifty-three portraits, which were recorded in a daybook maintained by Edward’s son, Isaac. The young Hicks charged as much as ten dollars per portrait. One of his first paintings is a portrait of his cousin Edward. Hicks depicted his cousin at the easel in front of a "Peaceable Kingdom" painting (c. 1836-7, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Williamsburg, Virginia).(4) It is the only known likeness of Edward Hicks with his famous work. An open "Bible" is on a table behind him and Edward is dressed in traditional Quaker minister dress. For unknown reasons, Hicks exacted a promise from his family that the portrait not be shown to anyone upon its completion. However, relative Edward Hicks Kennedy simply could not pass the chance, and wrote to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He requested special permission to enter Hicks, as the young artist was not yet the required age of fifteen.

Sometime in late 1836 or early 1837, Hicks, with a savings of one hundred dollars, left Newtown for Philadelphia. Upon his arrival, he found at least sixteen sitters and began to study at the Academy.(5) Then, sometime in late 1837, the artist left for New York where he entered the National Academy of Design. While at the National Academy, Hicks executed a number of impressive portraits that demonstrated dramatic improvement in his brushwork and depiction of naturalism. His "Self-Portrait"(c. 1840-42, National Academy of Design) is painted in the tradition of the Dutch masters.(6) The artist represented himself half-length, in a dark jacket with a white shirt. The background is nondescript, painted in a neutral brown. His face is awash with light and he looks directly at the viewer. His curly brown locks are hardly discernible form the background. The painting recalls Dutch portraits in that Thomas worked from dark to light, allowing his face to emerge to confront the viewer.

Another notable portrait created during this time is that of fellow artist and friend "Martin Johnson Heade" (1841, Bucks County Mercer Museum). Heade also apprenticed with Edward in Newtown, and it has been suggested that Hicks taught Heade as well. Like in his "Self-Portrait," Hicks worked from the background forward. As Heade’s face emerges from darkness and is contrasted with his black coat, neck sash and stark white shirt. Heade’s skin is like porcelain, with flushed red cheeks and nose. Both the "Self- Portrait" and "Martin Johnson Heade" are impressive and skilled efforts from an artist who had yet to turn eighteen.

While in New York, Hicks must have been exposed to a variety of painting styles and to artists working in and around the city. One of the most challenging and interesting aspects of Thomas Hicks’s work is that throughout his career, the artist does not work in a consistent style. He had the ability to paint like an academic painter as seen in his portraits; however, at the same time he also painted in the genre style of William Sidney Mount. For example, "Calculating" (1844, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is a wonderful genre scene of a man sitting in a house writing in what is presumably an account book. He wears a bright red vest with a white shirt, black tie, gray coat, and black shoes. He wears a large dark gray stovepipe hat that covers his face as he looks down examining his books. A dog lies at his feet, and a jug and other household objects dot the foreground. The rest of the room is sparse, with a door at the back right opened to reveal an approaching visitor on horseback. The most likely explanation for such a difference in artistic style is that Hicks was experimenting to determine what suited him best.

In 1845, Hicks left New York to study in Europe. He first visited London, then traveled to Paris and eventually to Rome where he spent the majority of his time. Hicks was not alone in his studies and travels, as a number of American artists lived and worked in Rome. They usually lived together, shared studios, and spent their leisure time together. Hicks was among artists such as John Frederick Kensett (who became a life-long friend), Christopher Pearce Cranch, George and Burril Curtis, Benjamin Champney, and Thomas Crawford. During the winters they socialized at the Trattoria Lepre and the Caffe Grecco, and during the warmer months traveled to the Alban Hills, Tivoli, Florence, Naples and Capri for sketching tours.(7)

Unfortunately, many of Hicks’ works from this period are lost. A few do exist, such as "Italian Landscape" (1847-48, National Academy of Design). The painting is an interesting depiction of a rocky landscape with spots of grass and foliage. A man with a waking cane and hat, dressed in modest clothing stands on one of the rocks and is dwarfed by their size. A small townscape can be seen in the left background. The painting reveals that Hicks was still experimenting with style, as it does not have the precision and clarity of his earlier portraits. Instead, the work was painted with a combination of fleeting brushstrokes that recall impressionism and sharp delineation within the detail of the rocks.

While in Rome, Hicks also copied a number of Old Master paintings, such as "Portrait of Raphael" (after Raphael) and "Marriage of St. Catherine" (after Correggio). His copy of Raphael’s "Portrait of Pope Julius II" (Raphael’s original, c. 1512-14, National Gallery, London) was said to be so close to the original that he was ordered (it is not known by whom) to change the dimensions of the pope’s chair so it would not be confused with the Raphael. The locations of these paintings are unknown. In 1848, Hicks traveled to Paris where he studio with French artist Thomas Couture. Little is known of his work that was created during his study in Paris.

In 1849, Hicks returned to New York and set up a portrait studio there. He also resumed his affiliation with the National Academy and in 1851 was elected a full member. During the 1850s, Hicks ran a successful portrait business. He became one of the most fashionable portraitists in New York, painting not only aristocrats, but also New York politicians. During this period, he also painted Harriet Beecher Elizabeth Stowe (1855, National Academy of Design), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1855, Longfellow National Historical Site) and Oliver Wendell Holmes (1858, Boston Athenaeum).

In 1853, Hicks married Angelina King of Brooklyn. She was from a well-to-do family and introduced him to the New York literary and high society circles. The couple entertained in their home on Layfayette Place and Hicks established a studio next door at Astor Place. After the mid 1850s, Hicks and his wife spent summer and early autumn at Thornwood, a country home they built near Trenton Falls (north of Utica in upstate New York). Close to their location was the Trenton Falls Hotel, which became a popular summer resort for New York’s wealthy elite. Hicks not only continued to paint portraits, but also began to focus on landscape. A few of his landscapes and figure paintings survive, but most are unlocated.

Hicks also continued to paint genre scenes, such as "The Musicale, Barber Shop, Trenton Falls" (1866, North Carolina Museum of Art). The painting was commissioned by Charles Teft and is a view of a music-making barbershop that existed on the hotel grounds. Teft is seated at the lower left, Hicks stands near the doorway sketching the scene. William Brisler, the chief barber and gatekeeper of the falls stands with the musicians singing and Angie Hicks is standing among the women that gather outside the door.(8) According to Tatham, the painting recalls Mount’s "The Power of Music" (1847, Museums at Stony Brook). Mount and Hicks were acquainted, but there is no reason to suppose Hicks had seen Mount’s painting.(9)'

In 1858, Hicks was among fifteen artists and five photographers invited by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to help popularize the railroad.(10) Other artists that participated included Kensett, John W. Ehninger, DeWitt C. Hitchcock, James Suydam, and James Henry Beard. Called the “Artist’s Excursion,” the purpose was to draw attention to the tourist appeal of the trans-Allegheny line. Artists were encouraged to examine not only “the magnificent scenery” along the route, but also “the notable productions of human science and labor.” (11)

In 1860, Hicks received a once in a lifetime chance to paint the likeness of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln (1860, Chicago Historical Society). It is purportedly the first portrait painted of Lincoln from life. Sometime in early 1860, a Chicago art dealer contacted Hicks and commissioned him to paint Lincoln’s portrait while he was in Springfield, Illinois. The purpose was for the portrait to be engraved so it could be used in election propaganda. Supposedly, Lincoln later wrote to the artist, informing him it was the best likeness of himself he had ever seen.

According to Tatham, in the 1860s, Hicks abandoned “the meticulous delineation of detail in his landscapes and adopted a more generalized approach, one that showed some affinity with Tonalism and Impressionism.” (12) The artist was certainly aware of the developments in style as he avidly participated in the arts community in New York and made occasional trips back to France. Hicks was associated with the Century Club, and painted a number of portraits of their founders over the course of the 1860s. He exhibited at the National Academy of Design, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Brooklyn Art Museum. He continued to paint portraits of famous personages such as actor Edwin Thomas Booth ("Edwin Thomas Booth as Iago," 1863, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D. C.).

At this time, Hicks began copying other well-known portraits. For example, he copied R. W. Wier’s "Chief Red Jacket" from 1828 (Hicks’ version, 1867, National Portrait Gallery). It was during this period that he painted the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts’ "Portrait of George Washington" (1867), which was copied after Gilbert Stuart’s famous Boston Athenaeum portrait.(13) Hicks continued to make copies of other paintings into the 1870s, including Kensett’s "Eagle Rock, Manchester, Massachusetts" of 1859 (Hicks’ version, 1875, location unknown). In 1879, Hicks’ painted another version of George Washington, which is now in the State House in Trenton, New Jersey.

During the 1860s, Hicks also began to paint domestic interiors. The works focused predominantly on old kitchens and rustic fireplaces, and sometimes incorporated figures.(14) For example, in "The Home Guard" (1863, National Academy of Design) Hicks depicted a young woman and her mother knitting in front of a large fireplace. A man, who is dressed in full Union uniform, sits in front of the young woman and her mother. Clearly smitten with the young lady, he helps her keep the yarn untangled for her mother. The mother glares at the young man, while the young woman looks at the viewer. The house is filled with objects, such as pots and pans, fruit baskets, and other domestic tools.(15) A dog lies just behind the girl, watching a black cat play with yarn in the foreground.

For the last twenty years of his life, Hicks continued to paint portraits and landscape scenes in and around Trenton Falls. Scholars do know that Hicks and his wife continued to live at Trenton Falls, and in New York, as Hicks seasonally appeared in the New York Times in regard to exhibitions and other artist activities. It seems that he kept company with the same group of people, Kensett being the most important. His painting does appear to slow down as he became older. Of his known works, it can be concluded that he created approximately three to four paintings a year from the mid 1870s until his death. Also, the fact that his style of portrait painting fell out of fashion about 1875 could account for the fewer works. One of his most impressive later works is a portrait of Union General Gordon Meade (1873, Union League Club). Hicks represented the General in a three quarter-length pose with his torso turned slightly to the right and his face in profile. The General is in full dress, grasping his sword with his left hand and stands in front of a vast landscape. It is a commanding, if not intimidating portrait of the Civil War General.

Hicks died in 1890, and his wife continued to summer at Thornwood in Trenton Falls until her death in 1917. Unfortunately, it seems that she preserved only a small number of her husband’s paintings. Most were sold at auction in 1892 and have since been difficult to locate. Any papers or personal correspondences she either sold or destroyed. What she did keep was the manuscript poetry and correspondences of poet-diplomat George Henry Boker of Philadelphia. The nature of their relationship is unknown, and it unclear if Hicks was aware of their friendship when he was alive.

1) In "Art and Artists in Connecticut" (1879, p. 121), Harry W. French wrote: “It would be impossible, within the limits of the subject, to offer to Mr. Hicks so much as a salutation from the State in accord with his position in art and society; so that, attempting nothing more, the visit is simply recorded with reference to the influence that must be extended by the presence of such a visitor.”

2) David Tatham, “Thomas Hicks at Trenton Falls,” "The American Art Journal" 20, no. 4 (1983): 5.

3) Even the schools which he attended, such as the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia have little or no information on the artist due to the fact that he attended when records simply were not kept, other than a one line note that he was there during x years.

4) Hicks painted two more versions of his Portrait of Edward Hicks: the second is dated 1839 and located at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D. C. and the third is dated c. 1850-52 and is located at the James Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

5) The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts unfortunately has no records of Thomas’ attendance due to the fact that records were not kept that early. Cheryl Liebold, archivist at the Academy, informed me that often times, aspiring artists were allowed to come to the Academy and study from plaster casts and other works of art. Presumably, this is what Hicks did.

6) Hicks began exhibiting his works at the National Academy in 1839, and his works continued to be exhibited there until after his death in 1890.

7) Several academies were open to American Students in Rome, and it is possible they attended. They included: the Academy of St. Luke, the Italian Academy, the British Academy, and the French Academy. It was also in Rome that dangerous events began to mark Hicks’ life. During Carnival in 1846, he was stabbed in the back with a stiletto, receiving critical injuries. After several months of recovery, the artist was back to his normal self, and resumed traveling and painting with his friends. After his marriage, he and his wife survived a train wreck in Connecticut, which killed thirty to forty people. Hicks was mistakenly listed as killed in the initial report in the New York Times.

8) The shop was supposed to be a haven for the men, but according to Hicks, the music drew the women like moth to a flame.

9) For more, see Tatham, pp. 12-13.

10) In the late 1850s, the B&O was the first rail to promote its commercial interests through the visual arts. They published travel guides, organized tours, and publicized scenic attractions on its route. For more, see Leo Danly and Susan Marx, eds., "The Railroad in American Art: Representations of Technological Change," 1988.

11) Danly and Marx, p. 5. For a first hand account, see D. H. Strother, “Artist’s Excursion over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad,” "Harper’s New Monthly Magazine" 19 (1859).

12) Tatham, p.13.

13) Since the painting was copied directly from the original, this means that Hicks was in Boston for at least a short period of time. What his activities were there other than copying the Stuart painting is unknown. It is possible that he accepted commissions while there.

14) The popularity of old-time kitchens as a subject for American artists dates from the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair of 1864 and the huge success there of its New England kitchen. It was a precursor of colonial period rooms that came to be installed in a number of American museums in the early decades of the early twentieth century. See Tatham, p. 13.

15) The large amount of additional objects in the scene is typical of the artist. In his larger portraits, he often packed the scene with items accoutrements of the sitter’s occupation.

-Letha Clair Robertson, 12/19/03

Image credit: Unknown Artist, Thomas Hicks, about 1865, albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; gift of Sandra and Jacob Terner, NPG.76.76, Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

American

(Newtown, Pennsylvania, 1823 - 1890, Trenton Falls, New York)

One of the great absurdities in the discipline of American art history is that modern art historians, examining almost four hundred years of art, can effectively decide what is good, mediocre or bad art. With the stroke of a pen, an artist’s entire career can virtually be eliminated from the history of American art, based on the opinion of a single scholar. Such is the case with American portraitist Thomas Hicks (1823-90). In his own lifetime, Hicks was an extremely well known and affluent portraitist. He and his wife lived next door to the William and Caroline Astor in New York and associated with prominent social circles in the city. For almost twenty-five years, beginning in 1850, Hicks was ranked as one of the most fashionable and prosperous portrait painters in America. In 1866, when Hicks traveled to New Haven, Connecticut to paint copies of John Trumbull’s portrait of "Roger Sherman," the state replied that they were merely graced by the presence of such a great man.(1) Hicks is mentioned in a large number of nineteenth-century journals such as "Harper’s Weekly," "The Century," and "The New England Magazine" as a talented and influential portraitist—after all, he painted the first life portrait of Abraham Lincoln (Chicago Historical Society, 1860). Art historian David Tatham stated that Hicks’ personality contributed to his success—Hicks was said to be “an amusing mimic and a witty raconteur who in his early years in New York preserved something of the genteel bohemianism of his student days in Rome and Paris by wearing his hair in long flowing locks.”(2) Yet, after 1940, his name virtually disappeared from the annals of American art history.

Today, Hicks is most commonly mentioned in passing with his cousin Edward, the primitive painter of the "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings. As Tatham noted, it is incredible that Hicks, who received professional training in Philadelphia, New York, Paris and Rome, took a backseat to his cousin Edward who never received any formal training.(3) Tatham’s article, “Thomas Hicks at Trenton Falls,” is the most thorough examination of Thomas Hicks’ works ever published, and it focuses on his later landscapes and portraits painted at Trenton Falls, New Jersey. Edward has had a large number of books and articles written about his "Peaceable Kingdom" paintings alone. One can’t help but wonder why an artist such as Thomas Hicks, who was so highly respected and revered in his own time, has been lost to modern scholars. As a result, his biography is sketchy at best, but we do know major points and events in his life.

Thomas Hicks was born on October 18, 1823 in Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to Joseph and Jane Hicks. He was raised with seven brothers and sisters. Little is known of his early life until he entered his cousin Edward’s sign and coach making shop sometime around 1836. While apprenticing in Edward’s shop, Hicks executed at least fifty-three portraits, which were recorded in a daybook maintained by Edward’s son, Isaac. The young Hicks charged as much as ten dollars per portrait. One of his first paintings is a portrait of his cousin Edward. Hicks depicted his cousin at the easel in front of a "Peaceable Kingdom" painting (c. 1836-7, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Williamsburg, Virginia).(4) It is the only known likeness of Edward Hicks with his famous work. An open "Bible" is on a table behind him and Edward is dressed in traditional Quaker minister dress. For unknown reasons, Hicks exacted a promise from his family that the portrait not be shown to anyone upon its completion. However, relative Edward Hicks Kennedy simply could not pass the chance, and wrote to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. He requested special permission to enter Hicks, as the young artist was not yet the required age of fifteen.

Sometime in late 1836 or early 1837, Hicks, with a savings of one hundred dollars, left Newtown for Philadelphia. Upon his arrival, he found at least sixteen sitters and began to study at the Academy.(5) Then, sometime in late 1837, the artist left for New York where he entered the National Academy of Design. While at the National Academy, Hicks executed a number of impressive portraits that demonstrated dramatic improvement in his brushwork and depiction of naturalism. His "Self-Portrait"(c. 1840-42, National Academy of Design) is painted in the tradition of the Dutch masters.(6) The artist represented himself half-length, in a dark jacket with a white shirt. The background is nondescript, painted in a neutral brown. His face is awash with light and he looks directly at the viewer. His curly brown locks are hardly discernible form the background. The painting recalls Dutch portraits in that Thomas worked from dark to light, allowing his face to emerge to confront the viewer.

Another notable portrait created during this time is that of fellow artist and friend "Martin Johnson Heade" (1841, Bucks County Mercer Museum). Heade also apprenticed with Edward in Newtown, and it has been suggested that Hicks taught Heade as well. Like in his "Self-Portrait," Hicks worked from the background forward. As Heade’s face emerges from darkness and is contrasted with his black coat, neck sash and stark white shirt. Heade’s skin is like porcelain, with flushed red cheeks and nose. Both the "Self- Portrait" and "Martin Johnson Heade" are impressive and skilled efforts from an artist who had yet to turn eighteen.

While in New York, Hicks must have been exposed to a variety of painting styles and to artists working in and around the city. One of the most challenging and interesting aspects of Thomas Hicks’s work is that throughout his career, the artist does not work in a consistent style. He had the ability to paint like an academic painter as seen in his portraits; however, at the same time he also painted in the genre style of William Sidney Mount. For example, "Calculating" (1844, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is a wonderful genre scene of a man sitting in a house writing in what is presumably an account book. He wears a bright red vest with a white shirt, black tie, gray coat, and black shoes. He wears a large dark gray stovepipe hat that covers his face as he looks down examining his books. A dog lies at his feet, and a jug and other household objects dot the foreground. The rest of the room is sparse, with a door at the back right opened to reveal an approaching visitor on horseback. The most likely explanation for such a difference in artistic style is that Hicks was experimenting to determine what suited him best.

In 1845, Hicks left New York to study in Europe. He first visited London, then traveled to Paris and eventually to Rome where he spent the majority of his time. Hicks was not alone in his studies and travels, as a number of American artists lived and worked in Rome. They usually lived together, shared studios, and spent their leisure time together. Hicks was among artists such as John Frederick Kensett (who became a life-long friend), Christopher Pearce Cranch, George and Burril Curtis, Benjamin Champney, and Thomas Crawford. During the winters they socialized at the Trattoria Lepre and the Caffe Grecco, and during the warmer months traveled to the Alban Hills, Tivoli, Florence, Naples and Capri for sketching tours.(7)

Unfortunately, many of Hicks’ works from this period are lost. A few do exist, such as "Italian Landscape" (1847-48, National Academy of Design). The painting is an interesting depiction of a rocky landscape with spots of grass and foliage. A man with a waking cane and hat, dressed in modest clothing stands on one of the rocks and is dwarfed by their size. A small townscape can be seen in the left background. The painting reveals that Hicks was still experimenting with style, as it does not have the precision and clarity of his earlier portraits. Instead, the work was painted with a combination of fleeting brushstrokes that recall impressionism and sharp delineation within the detail of the rocks.

While in Rome, Hicks also copied a number of Old Master paintings, such as "Portrait of Raphael" (after Raphael) and "Marriage of St. Catherine" (after Correggio). His copy of Raphael’s "Portrait of Pope Julius II" (Raphael’s original, c. 1512-14, National Gallery, London) was said to be so close to the original that he was ordered (it is not known by whom) to change the dimensions of the pope’s chair so it would not be confused with the Raphael. The locations of these paintings are unknown. In 1848, Hicks traveled to Paris where he studio with French artist Thomas Couture. Little is known of his work that was created during his study in Paris.

In 1849, Hicks returned to New York and set up a portrait studio there. He also resumed his affiliation with the National Academy and in 1851 was elected a full member. During the 1850s, Hicks ran a successful portrait business. He became one of the most fashionable portraitists in New York, painting not only aristocrats, but also New York politicians. During this period, he also painted Harriet Beecher Elizabeth Stowe (1855, National Academy of Design), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1855, Longfellow National Historical Site) and Oliver Wendell Holmes (1858, Boston Athenaeum).

In 1853, Hicks married Angelina King of Brooklyn. She was from a well-to-do family and introduced him to the New York literary and high society circles. The couple entertained in their home on Layfayette Place and Hicks established a studio next door at Astor Place. After the mid 1850s, Hicks and his wife spent summer and early autumn at Thornwood, a country home they built near Trenton Falls (north of Utica in upstate New York). Close to their location was the Trenton Falls Hotel, which became a popular summer resort for New York’s wealthy elite. Hicks not only continued to paint portraits, but also began to focus on landscape. A few of his landscapes and figure paintings survive, but most are unlocated.

Hicks also continued to paint genre scenes, such as "The Musicale, Barber Shop, Trenton Falls" (1866, North Carolina Museum of Art). The painting was commissioned by Charles Teft and is a view of a music-making barbershop that existed on the hotel grounds. Teft is seated at the lower left, Hicks stands near the doorway sketching the scene. William Brisler, the chief barber and gatekeeper of the falls stands with the musicians singing and Angie Hicks is standing among the women that gather outside the door.(8) According to Tatham, the painting recalls Mount’s "The Power of Music" (1847, Museums at Stony Brook). Mount and Hicks were acquainted, but there is no reason to suppose Hicks had seen Mount’s painting.(9)'

In 1858, Hicks was among fifteen artists and five photographers invited by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to help popularize the railroad.(10) Other artists that participated included Kensett, John W. Ehninger, DeWitt C. Hitchcock, James Suydam, and James Henry Beard. Called the “Artist’s Excursion,” the purpose was to draw attention to the tourist appeal of the trans-Allegheny line. Artists were encouraged to examine not only “the magnificent scenery” along the route, but also “the notable productions of human science and labor.” (11)

In 1860, Hicks received a once in a lifetime chance to paint the likeness of Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln (1860, Chicago Historical Society). It is purportedly the first portrait painted of Lincoln from life. Sometime in early 1860, a Chicago art dealer contacted Hicks and commissioned him to paint Lincoln’s portrait while he was in Springfield, Illinois. The purpose was for the portrait to be engraved so it could be used in election propaganda. Supposedly, Lincoln later wrote to the artist, informing him it was the best likeness of himself he had ever seen.

According to Tatham, in the 1860s, Hicks abandoned “the meticulous delineation of detail in his landscapes and adopted a more generalized approach, one that showed some affinity with Tonalism and Impressionism.” (12) The artist was certainly aware of the developments in style as he avidly participated in the arts community in New York and made occasional trips back to France. Hicks was associated with the Century Club, and painted a number of portraits of their founders over the course of the 1860s. He exhibited at the National Academy of Design, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Brooklyn Art Museum. He continued to paint portraits of famous personages such as actor Edwin Thomas Booth ("Edwin Thomas Booth as Iago," 1863, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D. C.).

At this time, Hicks began copying other well-known portraits. For example, he copied R. W. Wier’s "Chief Red Jacket" from 1828 (Hicks’ version, 1867, National Portrait Gallery). It was during this period that he painted the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts’ "Portrait of George Washington" (1867), which was copied after Gilbert Stuart’s famous Boston Athenaeum portrait.(13) Hicks continued to make copies of other paintings into the 1870s, including Kensett’s "Eagle Rock, Manchester, Massachusetts" of 1859 (Hicks’ version, 1875, location unknown). In 1879, Hicks’ painted another version of George Washington, which is now in the State House in Trenton, New Jersey.

During the 1860s, Hicks also began to paint domestic interiors. The works focused predominantly on old kitchens and rustic fireplaces, and sometimes incorporated figures.(14) For example, in "The Home Guard" (1863, National Academy of Design) Hicks depicted a young woman and her mother knitting in front of a large fireplace. A man, who is dressed in full Union uniform, sits in front of the young woman and her mother. Clearly smitten with the young lady, he helps her keep the yarn untangled for her mother. The mother glares at the young man, while the young woman looks at the viewer. The house is filled with objects, such as pots and pans, fruit baskets, and other domestic tools.(15) A dog lies just behind the girl, watching a black cat play with yarn in the foreground.

For the last twenty years of his life, Hicks continued to paint portraits and landscape scenes in and around Trenton Falls. Scholars do know that Hicks and his wife continued to live at Trenton Falls, and in New York, as Hicks seasonally appeared in the New York Times in regard to exhibitions and other artist activities. It seems that he kept company with the same group of people, Kensett being the most important. His painting does appear to slow down as he became older. Of his known works, it can be concluded that he created approximately three to four paintings a year from the mid 1870s until his death. Also, the fact that his style of portrait painting fell out of fashion about 1875 could account for the fewer works. One of his most impressive later works is a portrait of Union General Gordon Meade (1873, Union League Club). Hicks represented the General in a three quarter-length pose with his torso turned slightly to the right and his face in profile. The General is in full dress, grasping his sword with his left hand and stands in front of a vast landscape. It is a commanding, if not intimidating portrait of the Civil War General.

Hicks died in 1890, and his wife continued to summer at Thornwood in Trenton Falls until her death in 1917. Unfortunately, it seems that she preserved only a small number of her husband’s paintings. Most were sold at auction in 1892 and have since been difficult to locate. Any papers or personal correspondences she either sold or destroyed. What she did keep was the manuscript poetry and correspondences of poet-diplomat George Henry Boker of Philadelphia. The nature of their relationship is unknown, and it unclear if Hicks was aware of their friendship when he was alive.

1) In "Art and Artists in Connecticut" (1879, p. 121), Harry W. French wrote: “It would be impossible, within the limits of the subject, to offer to Mr. Hicks so much as a salutation from the State in accord with his position in art and society; so that, attempting nothing more, the visit is simply recorded with reference to the influence that must be extended by the presence of such a visitor.”

2) David Tatham, “Thomas Hicks at Trenton Falls,” "The American Art Journal" 20, no. 4 (1983): 5.

3) Even the schools which he attended, such as the National Academy of Design in New York, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia have little or no information on the artist due to the fact that he attended when records simply were not kept, other than a one line note that he was there during x years.

4) Hicks painted two more versions of his Portrait of Edward Hicks: the second is dated 1839 and located at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D. C. and the third is dated c. 1850-52 and is located at the James Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

5) The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts unfortunately has no records of Thomas’ attendance due to the fact that records were not kept that early. Cheryl Liebold, archivist at the Academy, informed me that often times, aspiring artists were allowed to come to the Academy and study from plaster casts and other works of art. Presumably, this is what Hicks did.

6) Hicks began exhibiting his works at the National Academy in 1839, and his works continued to be exhibited there until after his death in 1890.

7) Several academies were open to American Students in Rome, and it is possible they attended. They included: the Academy of St. Luke, the Italian Academy, the British Academy, and the French Academy. It was also in Rome that dangerous events began to mark Hicks’ life. During Carnival in 1846, he was stabbed in the back with a stiletto, receiving critical injuries. After several months of recovery, the artist was back to his normal self, and resumed traveling and painting with his friends. After his marriage, he and his wife survived a train wreck in Connecticut, which killed thirty to forty people. Hicks was mistakenly listed as killed in the initial report in the New York Times.

8) The shop was supposed to be a haven for the men, but according to Hicks, the music drew the women like moth to a flame.

9) For more, see Tatham, pp. 12-13.

10) In the late 1850s, the B&O was the first rail to promote its commercial interests through the visual arts. They published travel guides, organized tours, and publicized scenic attractions on its route. For more, see Leo Danly and Susan Marx, eds., "The Railroad in American Art: Representations of Technological Change," 1988.

11) Danly and Marx, p. 5. For a first hand account, see D. H. Strother, “Artist’s Excursion over the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad,” "Harper’s New Monthly Magazine" 19 (1859).

12) Tatham, p.13.

13) Since the painting was copied directly from the original, this means that Hicks was in Boston for at least a short period of time. What his activities were there other than copying the Stuart painting is unknown. It is possible that he accepted commissions while there.

14) The popularity of old-time kitchens as a subject for American artists dates from the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair of 1864 and the huge success there of its New England kitchen. It was a precursor of colonial period rooms that came to be installed in a number of American museums in the early decades of the early twentieth century. See Tatham, p. 13.

15) The large amount of additional objects in the scene is typical of the artist. In his larger portraits, he often packed the scene with items accoutrements of the sitter’s occupation.

-Letha Clair Robertson, 12/19/03

Image credit: Unknown Artist, Thomas Hicks, about 1865, albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; gift of Sandra and Jacob Terner, NPG.76.76, Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Artist Objects