John George Brown

American

(Durham, England, 1831 – 1913, New York, New York)

One of the most popular artist of the late nineteenth century, John George Brown’s images of the street children of New York charmed and captured audiences for decades. Brown’s winsome children appealed to those who appreciated sentiment and the works symbolized America’s lost, innocent past and her hope for the future. Brown’s lesser-known works of the elderly and the fishermen of Grand Menan Island are just as remarkable and noteworthy. When he died in 1913, Brown’s images of children were widely reproduced in weekly magazines and collected by art lovers all over the country. Perhaps most importantly, his paintings, along with the humanitarian efforts of and the literary works of Horatio Alger, brought attention to the ongoing problem of homeless children in the streets of the New York at the end of the nineteenth century.

John George Brown was born near Durham, England on November 11, 1831. His parents were against the idea of their son becoming an artist and apprenticed him to a glass company in Newcastle-on-Tyne at the age of fourteen. During his apprenticeship, he enrolled in evening art classes taught by William Bell Scott (who was associated with the Pre-Raphaelites) at the Government School of Design in Newcastle. His father was financially unsuccessful as an attorney, and the young man sent half of his meager wages to his family. Upon completion of his apprenticeship, Brown moved to Edinburgh, where he began to work at the Holyrood Glass Works. He continued his art studies at the Royal Scottish Academy and studied under Robert Scott Lauder. In 1853, Brown received a prize in the antique class for his work. (None of is student work is known to have survived.) That same year, the artist moved to London where he made designs for paintings on glass and sold portraits for nominal fees. He was in London only three months before immigrating to America.

Brown arrived in New York at the age of twenty-two and settled in Brooklyn. As he had done in England, he sought work at a glass factory, Brooklyn Flint, and enrolled at the Graham Art School, the first free art academy in Brooklyn. In 1855, Brown married his employer’s daughter, Mary Owen. By all accounts, Mary father supported the couple so that Brown could begin to paint full time.(1) Unfortunately, by 1856, Brown’s father-in-law died and the young couple began to struggle financially. When the Panic of 1857 hit, the glass factory closed, and Brown began to take steps to build his career.

He enrolled in the National Academy of Design’s antique and life classes, where Thomas Cummings taught him. Brown was at the Academy for a year and he also became active in the Brooklyn art community. He was a founding member in 1859 of the Brooklyn Art School, and two years later the Brooklyn Art Association. He made important connections, such as Samuel P. Avery, who proved to be instrumental in launching Brown’s career. By the summer of 1860, Brown had moved into the famous Tenth Street studio building. He kept his studio there for fifty-three years, making him one of the longest tenants in the building’s history.

Brown’s earliest known works, such as "Claiming the Shot: After the Hunt in the Adirondacks" (1865, Detroit Institute of Arts) and "Curling:—a Scottish game, at Central Park" (1863, Lady Eden, daughter of Robert Gordon, whose great-uncle, Robert Gordon, is featured in the painting), are groups of upper class figures, enjoying leisure time. In "Curling," a group of men play a game on the ice and two small girls are sledding in the left hand corner. The girl that sits on the sled pauses to look directly at the viewer with an amused smile—a hint of Brown’s well-known street urchin paintings. In "Claiming the Shot," a group of upper class men have stopped to swap hunting stories. They dogs rest and one gentleman places his hand on the freshly shot deer. A very robust man in the center of the composition is believed to be John Jacob Astor. A year prior to "Claiming the Shot," Brown painted a delightful portrait of Astor, dressed again in his hunting gear and looking rather portly (1864, Kennedy Galleries).

Brown’s other works of this period are typically children imitating adult activities, such as courtship rituals, or children at play. For example, "Little Queen of the Woods" (1866, The Jones Library, Inc., Amherst, Massachusetts) is a charming depiction of a little girl hiding in the woods. She stands underneath a cluster of trees, emphasized by broken sunlight that shines through the branches and leaves. The work is clearly Pre-Raphaelite influenced, as Brown has paid strict attention to the depiction of nature. The trees, sunlight, and shadows are painted with painstaking realism. Brown characteristically developed his themes in clusters. As he painted a series of adult group scenes, he also painted a series of children in the country as with "Little Queen of the Woods." One his best known country scenes is "The Berry Boy" (c. 1877, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum) in which a young working boy is caught by the viewer while he is scaling a small wall with his bucket of berries. His radiant smile and pose communicate the joy of being outside on a sunny day.

As early as 1861, Brown began painting street vendors and children. The representation of street merchants had a history in French and English art, dating back to the eighteenth century. Fruit vendors and flower girls became a favorite subject in nineteenth-century English art and they were usually portrayed as attractive and appealing children. American artists began to represent street scenes by the 1840s; however, these subjects did not gain wide popularity until the late 1870s and 1880s. Americans chose to paint street musicians, merchants, and beggars, since they were already established subjects in European art. Brown successfully adapted this subject matter and thus built his career.

Two pendant paintings, "Allegro" and "Penseroso" (Corcoran Gallery of Art), dated 1864 and 1865, are among Brown’s earliest representations of street children. In "Allegro," a child dressed in tattered clothing leans against a brick doorway, standing in profile, smoking a cigarette or cigar. In "Penseroso," another street child leans against the same doorway, also dressed in tattered clothing. However, he looks sadly pathetic, gazing directly at the viewer. Newsboys were also a popular depiction in American art and figured into American genre painting by the 1860s. In "Country Paths and City Sidewalks: The Art of John G. Brown," art historian Martha J. Hoppin explains that this was largely because the newspaper itself symbolized the glorious future of American democracy. Brown portrayed newsboys occasionally. It was his representations of bootblacks that brought him wide acclaim.

After 1875 Brown narrowed his focus to the bootblack. While many types of street vendors had been represented in art before, the bootblack was solely Brown’s invention in artistic subject matter. Most commonly, a single bootblack is represented, seated on a box (either a blacking box or packing crate) on a sidewalk, and dressed in tattered clothing. He is typically placed in front of a non-descript (cream or white) wall or a tattered worn door. The Museum’s "Shine, Mister ?"(1905) is one such painting. The bootblack works became so popular and widely produced that Brown began copyrighting the images, making sure that he received royalties from his images.

According to Hoppin, economic, social, and artistic factors lay behind Brown’s shift in focus from middle class country life to poor children. Before the Civil War, Americans had been aware of the rapid growth of cities and the dangers posed by deteriorating slums. From the 1870s on, the concern had risen to hear delirium after the Panic of 1873, giving rise to the first of many labor strikes. Renewed reform efforts culminated in the Progressive Era of the late 1890s and early twentieth century. Children living and working on the streets posed a threat to society, as it symbolized the decay of the social fabric.

The numbers of street children dramatically increased by the 1850s when waves of immigrants caused population explosions in the cities. Immigrants lived in inadequate, grossly overcrowded tenements in lower Manhattan. Their children had nowhere to go but the streets, and many families depended on their income from selling or scavenging wares on the streets. The crises lead to the founding of the Children’s Aid Society in 1853 by Charles Loring Brace. Of special concern was the number of homeless or vagabond children who slept in boxes, on steam gratings, or in doorways, and survived through street work or theft. Brace placed thousands of children in foster homes, and established lodging houses in the worst slum districts of the city. The first of these houses, the Newsboys’ Lodging House opened in 1854, and was probably known by Brown. The artist may have in fact known Brace, whose story and cause was told in newspapers and magazines. Brown’s street children are similar to Brace’s stories in many ways, as they embody the independent spirits that Brace so often saw. Late in life Brown claimed a special affection for his subjects: “I do not paint poor boys solely because the public likes such pictures and pays me for them, but because I love the boys myself, for I, too, was once a poor lad like them.”(2)

Brown’s paintings were idealistic presentations of the children, and he was criticized for it. The street children were not often quite as clean or wholesome looking as Brown’s paintings, but usually filthy and covered with street grime. One need only to view the photographs of Lewis Hine, such as the Museum’s "Newsboy who begins work at daybreak, Mobile, Alabama" (1914), that document the child labor forces of the early twentieth century to gain perspective on the realities of living on the street. Brown’s paintings and Brace’s writings also shared ideals with the books of Horatio Alger. Alger was in fact influenced by Brace, and wrote his most famous novel, "Ragged Dick," after moving to New York in the fall of 1860. The hero of the story was a bootblack, and he based the characters on real street children he met in New York. According to Hoppin, the “books popularized the notion of the naturally noble, hard-working, bold, and courageous street boy who earns his way to respectability, and no doubt they helped to create a market for Brown’s paintings.” (3)

Although Brown continued to paint bootblacks into the 1890s, his compositions became repetitious and poses less natural. He had introduced another subject, the bootblack and his dog; however, even this slight change could not save his waning popularity. Also after 1890, the young bootblacks were replaces by adults who had stands and sold other wares. Just before his death, Brown lamented on the disappearance of the old bootblack, claiming that modern commercialism had driven these picturesque characters from the street. By 1900, he was painting history.

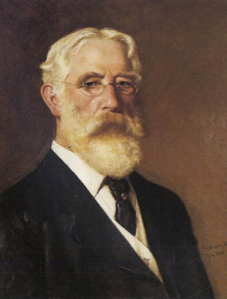

Some of Brown’s most poignant and lesser-known works are those he painted of the elderly after 1890. "The Boat Builder" (n.d. Cleveland Museum of Art) is a wonderful depiction of an elderly man in his shop. He sits in a chair in front of an old worn door (not unlike those that some of the bootblacks posed in front of) and slightly leans back in a wooden chair. His dog lies at his feet, and the shop is scattered with various tools and accoutrements of the boat making profession. When compared with a self-portrait dated after 1905, one realizes that the artist portrayed himself in the guise of an old Yankee craftsman. Art historian Kathleen S. Placidi suggests that Brown chose to represent himself this way as a nostalgic yearning after the country’s lost agrarian past. The elderly are the antithesis of urban industrialization and mechanization. In fact, all of Brown’s late paintings of the elderly are depictions of country people in indoor rural settings. Unfortunately, by the time Brown reached the twentieth century, his popularity had declined and he realized he was a relic of a by-gone age. He died in February of 1913 at the age of eighty-two.

1) There are discrepancies in Brown’s early career. It is reported that he painted full time and was supported by his father-in-law, insinuating that he was able to quit working at the glass factory. However, it has also been reported that he did not quit the glass factory until it closed due to the Panic of 1857. Most likely, Brown continues to work there in some capacity until 1857.

2) “A Painter of Street Urchins,” The New York Times Magazine, August 27, 1899, p.4; quoted in Martha J. Hoppin, Country Paths and City Sidewalks: The Art of J. G. Brown (Springfield, Massachusetts: George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, 1998): 22.

3) Ibid, 25.

- Letha Clair Robertson 4/19/04

Image credit: John George Brown, Self-Portrait, 1908, oil on canvas, Photohgraph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, (c) PD-US-expired

American

(Durham, England, 1831 – 1913, New York, New York)

One of the most popular artist of the late nineteenth century, John George Brown’s images of the street children of New York charmed and captured audiences for decades. Brown’s winsome children appealed to those who appreciated sentiment and the works symbolized America’s lost, innocent past and her hope for the future. Brown’s lesser-known works of the elderly and the fishermen of Grand Menan Island are just as remarkable and noteworthy. When he died in 1913, Brown’s images of children were widely reproduced in weekly magazines and collected by art lovers all over the country. Perhaps most importantly, his paintings, along with the humanitarian efforts of and the literary works of Horatio Alger, brought attention to the ongoing problem of homeless children in the streets of the New York at the end of the nineteenth century.

John George Brown was born near Durham, England on November 11, 1831. His parents were against the idea of their son becoming an artist and apprenticed him to a glass company in Newcastle-on-Tyne at the age of fourteen. During his apprenticeship, he enrolled in evening art classes taught by William Bell Scott (who was associated with the Pre-Raphaelites) at the Government School of Design in Newcastle. His father was financially unsuccessful as an attorney, and the young man sent half of his meager wages to his family. Upon completion of his apprenticeship, Brown moved to Edinburgh, where he began to work at the Holyrood Glass Works. He continued his art studies at the Royal Scottish Academy and studied under Robert Scott Lauder. In 1853, Brown received a prize in the antique class for his work. (None of is student work is known to have survived.) That same year, the artist moved to London where he made designs for paintings on glass and sold portraits for nominal fees. He was in London only three months before immigrating to America.

Brown arrived in New York at the age of twenty-two and settled in Brooklyn. As he had done in England, he sought work at a glass factory, Brooklyn Flint, and enrolled at the Graham Art School, the first free art academy in Brooklyn. In 1855, Brown married his employer’s daughter, Mary Owen. By all accounts, Mary father supported the couple so that Brown could begin to paint full time.(1) Unfortunately, by 1856, Brown’s father-in-law died and the young couple began to struggle financially. When the Panic of 1857 hit, the glass factory closed, and Brown began to take steps to build his career.

He enrolled in the National Academy of Design’s antique and life classes, where Thomas Cummings taught him. Brown was at the Academy for a year and he also became active in the Brooklyn art community. He was a founding member in 1859 of the Brooklyn Art School, and two years later the Brooklyn Art Association. He made important connections, such as Samuel P. Avery, who proved to be instrumental in launching Brown’s career. By the summer of 1860, Brown had moved into the famous Tenth Street studio building. He kept his studio there for fifty-three years, making him one of the longest tenants in the building’s history.

Brown’s earliest known works, such as "Claiming the Shot: After the Hunt in the Adirondacks" (1865, Detroit Institute of Arts) and "Curling:—a Scottish game, at Central Park" (1863, Lady Eden, daughter of Robert Gordon, whose great-uncle, Robert Gordon, is featured in the painting), are groups of upper class figures, enjoying leisure time. In "Curling," a group of men play a game on the ice and two small girls are sledding in the left hand corner. The girl that sits on the sled pauses to look directly at the viewer with an amused smile—a hint of Brown’s well-known street urchin paintings. In "Claiming the Shot," a group of upper class men have stopped to swap hunting stories. They dogs rest and one gentleman places his hand on the freshly shot deer. A very robust man in the center of the composition is believed to be John Jacob Astor. A year prior to "Claiming the Shot," Brown painted a delightful portrait of Astor, dressed again in his hunting gear and looking rather portly (1864, Kennedy Galleries).

Brown’s other works of this period are typically children imitating adult activities, such as courtship rituals, or children at play. For example, "Little Queen of the Woods" (1866, The Jones Library, Inc., Amherst, Massachusetts) is a charming depiction of a little girl hiding in the woods. She stands underneath a cluster of trees, emphasized by broken sunlight that shines through the branches and leaves. The work is clearly Pre-Raphaelite influenced, as Brown has paid strict attention to the depiction of nature. The trees, sunlight, and shadows are painted with painstaking realism. Brown characteristically developed his themes in clusters. As he painted a series of adult group scenes, he also painted a series of children in the country as with "Little Queen of the Woods." One his best known country scenes is "The Berry Boy" (c. 1877, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum) in which a young working boy is caught by the viewer while he is scaling a small wall with his bucket of berries. His radiant smile and pose communicate the joy of being outside on a sunny day.

As early as 1861, Brown began painting street vendors and children. The representation of street merchants had a history in French and English art, dating back to the eighteenth century. Fruit vendors and flower girls became a favorite subject in nineteenth-century English art and they were usually portrayed as attractive and appealing children. American artists began to represent street scenes by the 1840s; however, these subjects did not gain wide popularity until the late 1870s and 1880s. Americans chose to paint street musicians, merchants, and beggars, since they were already established subjects in European art. Brown successfully adapted this subject matter and thus built his career.

Two pendant paintings, "Allegro" and "Penseroso" (Corcoran Gallery of Art), dated 1864 and 1865, are among Brown’s earliest representations of street children. In "Allegro," a child dressed in tattered clothing leans against a brick doorway, standing in profile, smoking a cigarette or cigar. In "Penseroso," another street child leans against the same doorway, also dressed in tattered clothing. However, he looks sadly pathetic, gazing directly at the viewer. Newsboys were also a popular depiction in American art and figured into American genre painting by the 1860s. In "Country Paths and City Sidewalks: The Art of John G. Brown," art historian Martha J. Hoppin explains that this was largely because the newspaper itself symbolized the glorious future of American democracy. Brown portrayed newsboys occasionally. It was his representations of bootblacks that brought him wide acclaim.

After 1875 Brown narrowed his focus to the bootblack. While many types of street vendors had been represented in art before, the bootblack was solely Brown’s invention in artistic subject matter. Most commonly, a single bootblack is represented, seated on a box (either a blacking box or packing crate) on a sidewalk, and dressed in tattered clothing. He is typically placed in front of a non-descript (cream or white) wall or a tattered worn door. The Museum’s "Shine, Mister ?"(1905) is one such painting. The bootblack works became so popular and widely produced that Brown began copyrighting the images, making sure that he received royalties from his images.

According to Hoppin, economic, social, and artistic factors lay behind Brown’s shift in focus from middle class country life to poor children. Before the Civil War, Americans had been aware of the rapid growth of cities and the dangers posed by deteriorating slums. From the 1870s on, the concern had risen to hear delirium after the Panic of 1873, giving rise to the first of many labor strikes. Renewed reform efforts culminated in the Progressive Era of the late 1890s and early twentieth century. Children living and working on the streets posed a threat to society, as it symbolized the decay of the social fabric.

The numbers of street children dramatically increased by the 1850s when waves of immigrants caused population explosions in the cities. Immigrants lived in inadequate, grossly overcrowded tenements in lower Manhattan. Their children had nowhere to go but the streets, and many families depended on their income from selling or scavenging wares on the streets. The crises lead to the founding of the Children’s Aid Society in 1853 by Charles Loring Brace. Of special concern was the number of homeless or vagabond children who slept in boxes, on steam gratings, or in doorways, and survived through street work or theft. Brace placed thousands of children in foster homes, and established lodging houses in the worst slum districts of the city. The first of these houses, the Newsboys’ Lodging House opened in 1854, and was probably known by Brown. The artist may have in fact known Brace, whose story and cause was told in newspapers and magazines. Brown’s street children are similar to Brace’s stories in many ways, as they embody the independent spirits that Brace so often saw. Late in life Brown claimed a special affection for his subjects: “I do not paint poor boys solely because the public likes such pictures and pays me for them, but because I love the boys myself, for I, too, was once a poor lad like them.”(2)

Brown’s paintings were idealistic presentations of the children, and he was criticized for it. The street children were not often quite as clean or wholesome looking as Brown’s paintings, but usually filthy and covered with street grime. One need only to view the photographs of Lewis Hine, such as the Museum’s "Newsboy who begins work at daybreak, Mobile, Alabama" (1914), that document the child labor forces of the early twentieth century to gain perspective on the realities of living on the street. Brown’s paintings and Brace’s writings also shared ideals with the books of Horatio Alger. Alger was in fact influenced by Brace, and wrote his most famous novel, "Ragged Dick," after moving to New York in the fall of 1860. The hero of the story was a bootblack, and he based the characters on real street children he met in New York. According to Hoppin, the “books popularized the notion of the naturally noble, hard-working, bold, and courageous street boy who earns his way to respectability, and no doubt they helped to create a market for Brown’s paintings.” (3)

Although Brown continued to paint bootblacks into the 1890s, his compositions became repetitious and poses less natural. He had introduced another subject, the bootblack and his dog; however, even this slight change could not save his waning popularity. Also after 1890, the young bootblacks were replaces by adults who had stands and sold other wares. Just before his death, Brown lamented on the disappearance of the old bootblack, claiming that modern commercialism had driven these picturesque characters from the street. By 1900, he was painting history.

Some of Brown’s most poignant and lesser-known works are those he painted of the elderly after 1890. "The Boat Builder" (n.d. Cleveland Museum of Art) is a wonderful depiction of an elderly man in his shop. He sits in a chair in front of an old worn door (not unlike those that some of the bootblacks posed in front of) and slightly leans back in a wooden chair. His dog lies at his feet, and the shop is scattered with various tools and accoutrements of the boat making profession. When compared with a self-portrait dated after 1905, one realizes that the artist portrayed himself in the guise of an old Yankee craftsman. Art historian Kathleen S. Placidi suggests that Brown chose to represent himself this way as a nostalgic yearning after the country’s lost agrarian past. The elderly are the antithesis of urban industrialization and mechanization. In fact, all of Brown’s late paintings of the elderly are depictions of country people in indoor rural settings. Unfortunately, by the time Brown reached the twentieth century, his popularity had declined and he realized he was a relic of a by-gone age. He died in February of 1913 at the age of eighty-two.

1) There are discrepancies in Brown’s early career. It is reported that he painted full time and was supported by his father-in-law, insinuating that he was able to quit working at the glass factory. However, it has also been reported that he did not quit the glass factory until it closed due to the Panic of 1857. Most likely, Brown continues to work there in some capacity until 1857.

2) “A Painter of Street Urchins,” The New York Times Magazine, August 27, 1899, p.4; quoted in Martha J. Hoppin, Country Paths and City Sidewalks: The Art of J. G. Brown (Springfield, Massachusetts: George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, 1998): 22.

3) Ibid, 25.

- Letha Clair Robertson 4/19/04

Image credit: John George Brown, Self-Portrait, 1908, oil on canvas, Photohgraph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, (c) PD-US-expired

Artist Objects