John Marin

American

(Rutherford, New Jersey, 1870 – 1953, Cape Split, Maine)

Born in Rutherford, New Jersey, on December 23, 1870, John Marin spent most of his childhood in Weehawken, New Jersey. Marin was raised by his extended family, as his mother died within days of his birth and his father was on the road working as an investor, merchant, and public accountant. His father provided well, and would support the artist well into his adulthood. As a child, Marin spent a great deal of time on his grandfather’s peach farm, exploring the surrounding woods along the Hackensack River and on the Palisades overlooking the Hudson. From an early age, he drew great pleasure in working and playing outdoors.

Around 1887 Marin briefly studied at the Stevens Institute of Technology, completing half a year of a three-year program, and eventually found work with an architect. Architecture had an enormous influence on Marin’s early art—Marin created a large number of architectural etchings and line was always a predominant force in his oeuvre. From 1899 to 1901, Marin was enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts where he studied under William Merritt Chase and Thomas Anshutz. Little, if any, of Marin’s student work seems to have survived. However, in 1900, the artist won a prize for his outdoor sketches of wild fowl and riverboats. Marin left Philadelphia in 1902 and began studying at the Art Student’s League in New York, where he studied with Frank Dumont and Arthur Dove.

The years 1905—1910 were of enormous importance to Marin’s career. In 1905, at the age of thirty-four, Marin traveled to Europe, remaining abroad for five years, with only one visit home during the winter of 1909-1910. Marin formed friendships that he would influence and mold his career. He maintained these important relationships for the rest of his life.

The artist primarily stayed in Paris, where his younger stepbrother, Charles Biting, and his wife, Edith, were living. Marin’s father was also in the city, and helped his son to set up a home and studio. Marin began making etchings of Paris.(1) His etchings, according to art historian Ruth E. Fine, provide a microcosm of his work, spanning from romantic lyricism to a tough modernist vision. The works most often recall the smoky atmospheric works of Whistler and Charles Méryon.

While in Paris, Marin met the photographer Edward Stiechen, who was closely associated with Alfred Stieglitz and his 291 Gallery in New York. Impressed with Marin’s talents, Stieglitz began showing the artist’s works in 1909. From that point on, Stieglitz became Marin’s number one supporter. The artist also became one of the elder photographer’s inner circles, which included Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove. Stieglitz was well known as a champion of modern art, and as a result, Marin was able to explore his subject matter in a more abstract form. Marin also met a colleague named Ernest Haskell, who encouraged the artist to visit Maine in 1914. Throughout his life, Marin claimed to have been indifferent to the Parisian art scene, but he surely saw the works of Cézanne and Matisse as he exhibited beside them.

In 1909-1910, Marin made a brief trip home before returning to the United States permanently. This brief trip seems to have affected his style significantly, and his approach to landscape changed dramatically. Previously, the artist had captured intimate scenes of Paris, depicting some of the city’s most famous monuments. However, upon his return to Paris after his visit home, the artist painted the Tyrol mountain range in France, his first serious exploration of the mountain landscape—a subject that was to be of great importance to his work. In "Tyrol Series" (1910, National Gallery of Art), Marin establishes a sense of grandeur and distance. Tall pine trees dot the foreground, while the mountains can be seen in the background, floating amid a purple and blue wash. The Tyrol series are freely worked, some with an underdrawing of incised line. The Tyrol watercolors give the viewer a sense of freedom, as if the artist has discovered his style and the momentum that will carry his art throughout his career.

Upon his return to America, Marin established a working pattern he was to follow the rest of his life. Winters were spent in the New York area focusing on scenes of the city. He also reworked and completed landscape ideas he had gathered outdoors in other seasons and he prepared for exhibitions. During spring and fall, he painted landscapes with sources in the environs of New York State and New Jersey. In the summers, the artist traveled the country and painted whatever region he was visiting.

In 1912, Marin married Marie Jane Hughes, and the couple had a son John, Jr., two years later. For the first several years of marriage, the family lived an unsettled existence, summering in various places, the most frequent being Maine. It was at this time that Marin began to focus on the landscape of suburban New York—a subject that gained the artist the most acclaim. One of the artist’s best-known series of New York scenes—and one that received accolades—is the works that represent the Woolworth Building. Painted around 1911-1912, the works are loosely rendered architectural studies that in certain aspects recall his early Paris etchings. However, as the paintings progress in the series, they become more abstract. For example, in "Woolworth Building, No. 31" (1912, National Gallery of Art), Marin depicts the building as if its sides have been opened up and flattened across the canvas. In contrast, "Woolworth Building, No. 28" (1912, National Gallery of Art), Marin depicts the building in its true three-dimensional form. Both paintings have smaller buildings, trees and the street at the base of the Woolworth Building, however, "No. 31" appears as if the foreground has been pushed into the building with curving lines. The sky interacts with the building—Marin painted loose blue strokes in angular positions jutting towards and away from the building. "No. 31" is a precursor to his New York movement series, as Marin is beginning to translate the pulsating motion of the city onto the paper. As Marin continued to explore the movement of the city in his watercolors, his work became increasingly abstracted into brilliantly colored lines that hint at a formal composition without being representational. They are diverse in their degree of abstraction and varied in the handling of paint and coloration. Marin’s later New York City watercolors, such as the Museum’s "Manhattan Movement" (1932), are an expressive explosion of color, emotion, and movement in a magical interpretation of a city that never sleeps.

Around 1915, Marin painted a series on nearby Weehawken Docks (New Jersey), which proved to be the artist’s most abstract works to date. Like his scenes of suburban New York, Marin experimented with representing recognizable form and his handling of color and line in order to provide a sense of place. For example, "Weehawken Sequence" (1915, Kennedy Galleries) focuses on central structures—buildings, a tower, trees, and other elements that make up the dock. Painted in thick brushstrokes loaded with oil, its subject matter is easily recognizable. In contrast, "Weehawken Sequence" (1915, Kennedy Galleries) is an almost total abstraction of the buildings at the docks. It too is painted in oil, with thick impasto and lines. It appears to be a birds-eye view, with the one recognizable feature being part of a roof of a building—the rest is completely abstracted. It is clear that Weehawken provided the artist with different inspiration than that of New York City, as the paintings lack the vibration and motion of his city landscapes.

In the summer of 1914, John Marin discovered Maine. Artists such as Winslow Homer and Albert Pinkham Ryder had painted the state before Marin, hoping to help shape the American landscape tradition. Marin’s paintings continued this celebration of the rugged individual alone in the wilderness.(2) However, Marin’s paintings bring the Maine landscape into the 20th century and into American modernism. No longer is landscape a purely representational subject, but it is an abstracted form represented by strokes of paint that emanate motion, light, color, and sound. Marin spent long periods of his life in Maine from 1914 until the end of his life, staying from early summer until Christmas. His first year there was focused in the West Point-Small Point area by Casco Bay, and provided relentless inspiration for the artist. The Museum’s "Small Point Harbor, Casco Bay, Maine" (1931) is one such painting. Marin even bought an island with an annual stipend provided by Stieglitz, gleefully naming it “Marin Island.”

Like his city landscapes of New York and Weehawken, New Jersey series, Marin’s Maine paintings were initially naturalistic and became abstract. For example, "On Marin Island" (1915, Private Collection) and "Marin Island" (1931, Aaron I. Fleischman), are contrasting representations of the same scene. The 1915 watercolor has a distinct landmass in the foreground and the island in the background, with water filling the middle ground. The landscape is clearly recognizable and naturalistic, with expressionistic squiggling lines making up the water. The 1931 painting is drastically different—Marin frames the image on the paper with black angular lines, a technique that became characteristic of his later works. The overall color scheme is darker, in contrast to the softer pastel colors of the 1915 version. The landscape in the 1931 version is made of up sharp angular lines with contained colors.

In 1929 and 1930, with encouragement from Rebecca Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Mabel Dodge Luhan, Marin visited New Mexico for the first time.(3) Marin stayed in New Mexico for several months, creating an impressive series of watercolors. He drove out daily to sites that interested him, and fished in between trips. "Autumn in New Mexico" (1930, Harvey and Françoise Rambach) is one of his most striking New Mexican works. In the painting, Marin captures a mountain range in a breathtaking cacophony of greens, blues, and purples, with peaks highlighted in yellows, oranges, and reds. The foreground is painted in browns, blacks, and gray washes, creating a line of shrubbery and vegetation across the front of the paper. Marin once again returned to naturalistic painting. However, in "The Mountain, Taos, New Mexico" (Private Collection), painted a year earlier, Marin has reduced the mountain range to a series of black lines filled with color—greens, oranges, purples, browns, and gray washes. The painting calls into question Marin’s claim that French artists such as Cezanne did not influence him, as the work recalls the French master’s famous interpretation of Mount St. Victoire.

Marin spent the summer of 1933 at Cape Split, Maine for the first time. According to Fine, the paintings the artist completed that year suggest that he felt an immediate surge of empathy—a sense of being at home again—similar to what he had experienced on his first visit to the Casco Bay area almost two decades earlier. By the time Marin settled in Cape Split, the sea was prevalent among his motifs. Marin portrayed the sea in all of its moods—calm or violent, gray or colorful, luminous or leaden.

"Wave on Rock"(1937, Whitney Museum of American Art) is one of Marin’s best-known sea paintings. In the oil on canvas painting, the waves crashing against the rocks have been reduced to abstract form, yet are still recognizable. The ocean is a rich aquamarine and blue, contrasted by the brilliant white sea foam of violent action. The French influence is again called into question with "Women Forms and Sea" (1934, Private Collection) as Marin introduced Matisse-like figures, which appear to float on top of the water.

In his late works of the 1940s and 1950s, Marin continued to reduce recognizable locations and objects to their purest form of color and line. He continued to represent New York City, mountainscapes, and the sea, yet they are a series of calligraphic lines and color that imply expressive emotion and intense concentration.

In 1950, Marin was the main representative of the United States at the Venice Biennale and was given the most space to fill, while the rest was shared by a number of younger abstractionist painters: Willem de Kooning, Lee Gatch, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky. Marin’s enthusiasm for life and painting never waned, and, according to Fine, he seemed put off by the Existential angst that was expressed by many of the younger painters. Modern art was no longer about representation, but abstraction in the expression of thought, mood, and emotion. A comment he made in 1947 best summarized his views: “[Shakespeare] didn’t give us tragedies only; he gave us comedies as well. I’d like the modern artists to think about that—there’s room in life for both and I’d like to see them restore the balance and give us something a little cheerful. The sun is still shining and there’s a lot of color in the world. Let’s see some of it on canvas.”(4) Marin died in 1953.

1) It is unknown exactly where Marin learned to make etchings.

2) As an adult, Marin was an avid outdoorsman—his love for nature had carried over from his childhood. See Ruth E. Fine, John Marin (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 166.

3) Rebecca Strand was the wife of Paul Strand, another intimate of Stieglitz’s circle. Mabel Dodge Luhan was a wealthy New York arts supporter who had moved out to New Mexico. Marin stayed at her estate while visiting.

4) Fine, 282.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 6/21/04

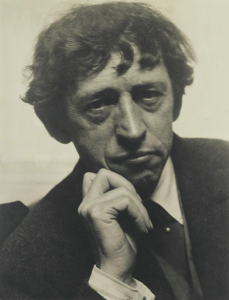

Image credit: Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946), John Marin, 1922, gelatin silver print, Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s

American

(Rutherford, New Jersey, 1870 – 1953, Cape Split, Maine)

Born in Rutherford, New Jersey, on December 23, 1870, John Marin spent most of his childhood in Weehawken, New Jersey. Marin was raised by his extended family, as his mother died within days of his birth and his father was on the road working as an investor, merchant, and public accountant. His father provided well, and would support the artist well into his adulthood. As a child, Marin spent a great deal of time on his grandfather’s peach farm, exploring the surrounding woods along the Hackensack River and on the Palisades overlooking the Hudson. From an early age, he drew great pleasure in working and playing outdoors.

Around 1887 Marin briefly studied at the Stevens Institute of Technology, completing half a year of a three-year program, and eventually found work with an architect. Architecture had an enormous influence on Marin’s early art—Marin created a large number of architectural etchings and line was always a predominant force in his oeuvre. From 1899 to 1901, Marin was enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts where he studied under William Merritt Chase and Thomas Anshutz. Little, if any, of Marin’s student work seems to have survived. However, in 1900, the artist won a prize for his outdoor sketches of wild fowl and riverboats. Marin left Philadelphia in 1902 and began studying at the Art Student’s League in New York, where he studied with Frank Dumont and Arthur Dove.

The years 1905—1910 were of enormous importance to Marin’s career. In 1905, at the age of thirty-four, Marin traveled to Europe, remaining abroad for five years, with only one visit home during the winter of 1909-1910. Marin formed friendships that he would influence and mold his career. He maintained these important relationships for the rest of his life.

The artist primarily stayed in Paris, where his younger stepbrother, Charles Biting, and his wife, Edith, were living. Marin’s father was also in the city, and helped his son to set up a home and studio. Marin began making etchings of Paris.(1) His etchings, according to art historian Ruth E. Fine, provide a microcosm of his work, spanning from romantic lyricism to a tough modernist vision. The works most often recall the smoky atmospheric works of Whistler and Charles Méryon.

While in Paris, Marin met the photographer Edward Stiechen, who was closely associated with Alfred Stieglitz and his 291 Gallery in New York. Impressed with Marin’s talents, Stieglitz began showing the artist’s works in 1909. From that point on, Stieglitz became Marin’s number one supporter. The artist also became one of the elder photographer’s inner circles, which included Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove. Stieglitz was well known as a champion of modern art, and as a result, Marin was able to explore his subject matter in a more abstract form. Marin also met a colleague named Ernest Haskell, who encouraged the artist to visit Maine in 1914. Throughout his life, Marin claimed to have been indifferent to the Parisian art scene, but he surely saw the works of Cézanne and Matisse as he exhibited beside them.

In 1909-1910, Marin made a brief trip home before returning to the United States permanently. This brief trip seems to have affected his style significantly, and his approach to landscape changed dramatically. Previously, the artist had captured intimate scenes of Paris, depicting some of the city’s most famous monuments. However, upon his return to Paris after his visit home, the artist painted the Tyrol mountain range in France, his first serious exploration of the mountain landscape—a subject that was to be of great importance to his work. In "Tyrol Series" (1910, National Gallery of Art), Marin establishes a sense of grandeur and distance. Tall pine trees dot the foreground, while the mountains can be seen in the background, floating amid a purple and blue wash. The Tyrol series are freely worked, some with an underdrawing of incised line. The Tyrol watercolors give the viewer a sense of freedom, as if the artist has discovered his style and the momentum that will carry his art throughout his career.

Upon his return to America, Marin established a working pattern he was to follow the rest of his life. Winters were spent in the New York area focusing on scenes of the city. He also reworked and completed landscape ideas he had gathered outdoors in other seasons and he prepared for exhibitions. During spring and fall, he painted landscapes with sources in the environs of New York State and New Jersey. In the summers, the artist traveled the country and painted whatever region he was visiting.

In 1912, Marin married Marie Jane Hughes, and the couple had a son John, Jr., two years later. For the first several years of marriage, the family lived an unsettled existence, summering in various places, the most frequent being Maine. It was at this time that Marin began to focus on the landscape of suburban New York—a subject that gained the artist the most acclaim. One of the artist’s best-known series of New York scenes—and one that received accolades—is the works that represent the Woolworth Building. Painted around 1911-1912, the works are loosely rendered architectural studies that in certain aspects recall his early Paris etchings. However, as the paintings progress in the series, they become more abstract. For example, in "Woolworth Building, No. 31" (1912, National Gallery of Art), Marin depicts the building as if its sides have been opened up and flattened across the canvas. In contrast, "Woolworth Building, No. 28" (1912, National Gallery of Art), Marin depicts the building in its true three-dimensional form. Both paintings have smaller buildings, trees and the street at the base of the Woolworth Building, however, "No. 31" appears as if the foreground has been pushed into the building with curving lines. The sky interacts with the building—Marin painted loose blue strokes in angular positions jutting towards and away from the building. "No. 31" is a precursor to his New York movement series, as Marin is beginning to translate the pulsating motion of the city onto the paper. As Marin continued to explore the movement of the city in his watercolors, his work became increasingly abstracted into brilliantly colored lines that hint at a formal composition without being representational. They are diverse in their degree of abstraction and varied in the handling of paint and coloration. Marin’s later New York City watercolors, such as the Museum’s "Manhattan Movement" (1932), are an expressive explosion of color, emotion, and movement in a magical interpretation of a city that never sleeps.

Around 1915, Marin painted a series on nearby Weehawken Docks (New Jersey), which proved to be the artist’s most abstract works to date. Like his scenes of suburban New York, Marin experimented with representing recognizable form and his handling of color and line in order to provide a sense of place. For example, "Weehawken Sequence" (1915, Kennedy Galleries) focuses on central structures—buildings, a tower, trees, and other elements that make up the dock. Painted in thick brushstrokes loaded with oil, its subject matter is easily recognizable. In contrast, "Weehawken Sequence" (1915, Kennedy Galleries) is an almost total abstraction of the buildings at the docks. It too is painted in oil, with thick impasto and lines. It appears to be a birds-eye view, with the one recognizable feature being part of a roof of a building—the rest is completely abstracted. It is clear that Weehawken provided the artist with different inspiration than that of New York City, as the paintings lack the vibration and motion of his city landscapes.

In the summer of 1914, John Marin discovered Maine. Artists such as Winslow Homer and Albert Pinkham Ryder had painted the state before Marin, hoping to help shape the American landscape tradition. Marin’s paintings continued this celebration of the rugged individual alone in the wilderness.(2) However, Marin’s paintings bring the Maine landscape into the 20th century and into American modernism. No longer is landscape a purely representational subject, but it is an abstracted form represented by strokes of paint that emanate motion, light, color, and sound. Marin spent long periods of his life in Maine from 1914 until the end of his life, staying from early summer until Christmas. His first year there was focused in the West Point-Small Point area by Casco Bay, and provided relentless inspiration for the artist. The Museum’s "Small Point Harbor, Casco Bay, Maine" (1931) is one such painting. Marin even bought an island with an annual stipend provided by Stieglitz, gleefully naming it “Marin Island.”

Like his city landscapes of New York and Weehawken, New Jersey series, Marin’s Maine paintings were initially naturalistic and became abstract. For example, "On Marin Island" (1915, Private Collection) and "Marin Island" (1931, Aaron I. Fleischman), are contrasting representations of the same scene. The 1915 watercolor has a distinct landmass in the foreground and the island in the background, with water filling the middle ground. The landscape is clearly recognizable and naturalistic, with expressionistic squiggling lines making up the water. The 1931 painting is drastically different—Marin frames the image on the paper with black angular lines, a technique that became characteristic of his later works. The overall color scheme is darker, in contrast to the softer pastel colors of the 1915 version. The landscape in the 1931 version is made of up sharp angular lines with contained colors.

In 1929 and 1930, with encouragement from Rebecca Strand, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Mabel Dodge Luhan, Marin visited New Mexico for the first time.(3) Marin stayed in New Mexico for several months, creating an impressive series of watercolors. He drove out daily to sites that interested him, and fished in between trips. "Autumn in New Mexico" (1930, Harvey and Françoise Rambach) is one of his most striking New Mexican works. In the painting, Marin captures a mountain range in a breathtaking cacophony of greens, blues, and purples, with peaks highlighted in yellows, oranges, and reds. The foreground is painted in browns, blacks, and gray washes, creating a line of shrubbery and vegetation across the front of the paper. Marin once again returned to naturalistic painting. However, in "The Mountain, Taos, New Mexico" (Private Collection), painted a year earlier, Marin has reduced the mountain range to a series of black lines filled with color—greens, oranges, purples, browns, and gray washes. The painting calls into question Marin’s claim that French artists such as Cezanne did not influence him, as the work recalls the French master’s famous interpretation of Mount St. Victoire.

Marin spent the summer of 1933 at Cape Split, Maine for the first time. According to Fine, the paintings the artist completed that year suggest that he felt an immediate surge of empathy—a sense of being at home again—similar to what he had experienced on his first visit to the Casco Bay area almost two decades earlier. By the time Marin settled in Cape Split, the sea was prevalent among his motifs. Marin portrayed the sea in all of its moods—calm or violent, gray or colorful, luminous or leaden.

"Wave on Rock"(1937, Whitney Museum of American Art) is one of Marin’s best-known sea paintings. In the oil on canvas painting, the waves crashing against the rocks have been reduced to abstract form, yet are still recognizable. The ocean is a rich aquamarine and blue, contrasted by the brilliant white sea foam of violent action. The French influence is again called into question with "Women Forms and Sea" (1934, Private Collection) as Marin introduced Matisse-like figures, which appear to float on top of the water.

In his late works of the 1940s and 1950s, Marin continued to reduce recognizable locations and objects to their purest form of color and line. He continued to represent New York City, mountainscapes, and the sea, yet they are a series of calligraphic lines and color that imply expressive emotion and intense concentration.

In 1950, Marin was the main representative of the United States at the Venice Biennale and was given the most space to fill, while the rest was shared by a number of younger abstractionist painters: Willem de Kooning, Lee Gatch, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky. Marin’s enthusiasm for life and painting never waned, and, according to Fine, he seemed put off by the Existential angst that was expressed by many of the younger painters. Modern art was no longer about representation, but abstraction in the expression of thought, mood, and emotion. A comment he made in 1947 best summarized his views: “[Shakespeare] didn’t give us tragedies only; he gave us comedies as well. I’d like the modern artists to think about that—there’s room in life for both and I’d like to see them restore the balance and give us something a little cheerful. The sun is still shining and there’s a lot of color in the world. Let’s see some of it on canvas.”(4) Marin died in 1953.

1) It is unknown exactly where Marin learned to make etchings.

2) As an adult, Marin was an avid outdoorsman—his love for nature had carried over from his childhood. See Ruth E. Fine, John Marin (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1990), 166.

3) Rebecca Strand was the wife of Paul Strand, another intimate of Stieglitz’s circle. Mabel Dodge Luhan was a wealthy New York arts supporter who had moved out to New Mexico. Marin stayed at her estate while visiting.

4) Fine, 282.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 6/21/04

Image credit: Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946), John Marin, 1922, gelatin silver print, Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s