Frederic Edwin Church

American

(Hartford, Connecticut, 1826 - 1900, New York, New York)

“I enjoy immensely the effort to reproduce some of the marvelous atmospheric effects which are so frequent here. It is attempting the impossible still I like to make the effort and have the satisfaction of knowing that I make some progress.”

- Frederic Church, 1898, in a letter to Martin Johnson Heade in regard to Mexico (1)

In 1859, Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861), a writer and friend of Frederic Edwin Church, wrote that Church was “an artist who could appeal both to the tastes of those who sought merely to be entertained by art and to those who desired to be instructed and morally uplifted by it.” (2) Church was not only one of America’s great landscape artists, trained under Hudson River School legend Thomas Cole, but he was also a great showman. Known primarily for his enormous paintings of natural wonders such as the Andes, Niagara Falls, and icebergs, Church was the initiator of the “Great Picture,” a single-work exhibition. The artist provided his audience with extraordinary panoramas of parts of the world they had never seen before. His paintings not only supported early Transcendentalist ideas of God and nature, but they also encouraged the American notion of Manifest Destiny. With the economy recovering and on the rise from the depression in the 1830s, Americans increasingly wanted to know what lay beyond the safety and boundaries of their own communities. Church traveled the world in search of magnificent vistas to record on canvas, literally risking life and limb by climbing rock faces and treacherous paths to obtain sketches for his works. As a result, Church provided Americans with some of the nineteenth-century's most enchanting and awe-inspiring views of nature.

Frederic Edwin Church was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1826. The only son of a highly successful businessman, Church demonstrated talent for the arts at an early age. While not completely enthusiastic about his son’s endeavors, Church’s father agreed to support his studies. In Hartford, Church took drawing and oil painting lessons, and in 1844, at the age of eighteen, the young artist was apprenticed to Hudson River artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848). By then, Cole had been the most famous and most respected landscape painter in America for almost twenty years, and, he had never taken a student. Cole’s acceptance of Church was not only based on the young artist’s talent, but also heavy persuasion from Henry Wadsworth of Hartford, an important patron of the arts.

Cole was well known in the New York cultural circles, and although his relationships with leading patrons and connoisseurs were often uneasy, he understood the market for landscape painting better than anyone else. This was an important facet to Church’s early study. Art critic Henry Tuckerman noted in 1866 that Church’s enterprise in marketing was an important aspect in his successful career.(3)

Aside from business smarts, Cole also imparted to Church his theories of landscape painting. Cole felt that landscape paintings should have higher aims than merely recording the literal appearance of the natural world. Cole preferred painting compositions that were based on the study of nature, but did not attempt to recreate specific scenes. Cole believed that the ultimate purpose of the landscape painter was to create “a higher sense of landscape” that could “speak a language strong, moral, and imaginative.”(4) By the time Church joined Cole in the Catskills in 1844, Cole felt more strongly about his “mission” as an artist and that landscape painting should not be a mere imitation of nature.

One year after his apprenticeship with Cole (1844-46), Church settled in New York and took a studio in the Art Union building. He made his professional debut and sent two landscapes—"Twilight among the Mountains" (c. 1845, Olana State Historical Site) and "Hudson Scenery" (c. 1845, unlocated)—to the National Academy of Design. According to art historian Franklin Kelly, far more genius was displayed in Church’s "Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford, in 1636" (1846, Wadsworth Athenaeum). The landscape sets the stage for an important human event—the founding of Hartford—thus becoming an historical landscape painting. In the painting, Church’s precise and crisp handling of paint is unlike Cole’s manner, however, the elevated theme of the picture was clearly indebted to Cole’s theory. As Kelly explains, Church made “an early step toward adapting Cole’s ambitions for landscape to the evolving taste in America of the 1840s which favored more straightforward and factual paintings.” (5)

As his confidence grew, Church began to create more ambitious works based on precedents from Cole’s art. Several critics warned of mimesis, but Church’s precise manner of painting and his careful observation of the effects of light and shadow made his work different. Cole died in 1848 (leaving Asher B. Durand as the leading landscape painter), and the same year, Church painted a stirring tribute to his former master. "To the Memory of Cole" (1848, Des Moines Women’s Club) is a landscape based on the topography of the Catskills. The central focus is a white stone cross draped in a floral garland. The cross is the middle of the bucolic countryside, spotlighted by a shaft of sunlight. The rest of the landscape is overcast by billowing clouds that roll across the canvas. The clouds reflect the sunlight coming from outside of the painting; some have a pink and orange hue while others are stark white. Overall, the scene has an ethereal appearance heightened by the lack of human presence.(6) As Kelly notes, the landscape is punctuated by signs of change and tradition, as light alternates dark and leaves turn red amid sprigs of growth. The painting is a meditation on time and a “contrast of the fleeting quality of human life with the enduring permanence of nature.” (7) "To the Memory of Cole" is a touching memorial to a landscape master.

Another influence on Church and other landscape artists was English art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900). Ruskin, who’s "Modern Painters" was becoming known in America, favored a factual portrayal of nature in art. He noted how the beauties of the natural world were reflections of the higher order and plan of God. Ruskin encouraged landscape painters to express the deeper meanings of nature. From this point on, Church would travel to the furthest reaches of the earth in order to capture magnificent views of nature on canvas.

In 1849, Church was elected full academician at the National Academy of Design and was now solidly established in New York as an artist. A new confidence arose in his work and himself, and he began to sell a greater number of paintings. The National Academy of Design and the American Art Union provided Church (as well as other artists) opportunities to sell and exhibit to a number of collectors who wanted high quality landscapes.

At the end of the 1840s and into the early 1850s, Church primarily focused on New England landscapes. The Museum’s "American Landscape" is from this period. These smaller landscapes represented views of America that were meant to evoke the essence of an entire region of America. For example, New England Scenery (1851, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Massachusetts) is an ideal scene bursting with images of God’s creations and abundance. A river dominates the foreground of the scene, which has attracted animals and humans alike—a house can be seen on a short bluff just above the river bed. A bridge with people crossing stretches across the foreground and lush trees and a mountainscape dominate the background. The painting didn’t represent once specific area in New England, but was made up of a number of specific characteristics of various parts of the northeast. This Zeuxian theory, whereby the most beautiful parts are selected and pieced together in order to create a harmonious whole, was characteristic of art practice since antiquity. This theory also echoed that of German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who was a strong influence on the direction Church’s art was about to take.

Humboldt, in "Cosmos: A Skretch of a Physical Description of the Universe" (1850), “attempted to synthesize existing scientific knowledge about the world into a grand theoretical system that could explain the underlying principles of the universe.” (8) Published before Darwin’s "The Origin of the Species" (1859), Humboldt provided the reader with a mix of rational science and the existence of a divine force for the world. The book confirmed Church’s beliefs and also included a section on landscape painting that encouraged artists to travel to parts unseen and record them on canvas. In 1853, Church would embark on a journey to South America with friend Cyrus W. Field, later promoter of Transatlantic Cable.

Church’s first South American paintings were compositionally similar to those of his North American works. The key difference was that within the work, Church depicted an exotic flora and fauna that was previously unseen by Eastern viewers, and provided a possible location for future expansion. Exhibited at the National Academy of Design in the fall of 1855, the works included: "The Cordilleras: Sunrise" (1854, Alexander Gallery, New York), "La Magdalena (Scene on the Magdalena)" (1854, National Academy of Design), "Tamaca Palms" (1854, Corcoran Gallery of Art, and "Tequendama Falls, near Bogota, New Granada" (1854, Cincinnati Art Museum). Their exhibition was a smashing success, but not nearly as breathtaking as "The Andes of Ecuador" (1855, Reynolda House, Museum of American Art).

"The Andes of Ecuador" was Church’s first large-scale painting, measuring 48 x 75 inches (4 x 6 feet). The artist chose to show it in Boston first, and when it came to the National Academy in 1857, the public and critics alike were astounded. The light in the painting was described as almost blinding the eye of the spectator, and another described it as “striking and bewildering.”(9) While the composition recalls earlier works, the landscape is opened up to the mountain chain with only a few trees to the left side of the canvas. Waterfalls are seen rushing throughout crevices in the mountain range. There are two Andean Indians underneath the trees at the left, and four llamas dot the center foreground of the painting. "The Andes of Ecuador" was a breakthrough for Church and with its inception, Church single-handedly changed American landscape painting. For the rest of his career, Church’s audience expected nothing but enormous and magnificent vistas.

Church’s next large project was "Niagara" (1857, Corcoran Gallery of Art). By the mid-nineteenth century, Niagara Falls was just developing as a tourist attraction, and the journey to reach the Falls was quite treacherous. Church, as by now had become customary, had made numerous sketches from multiple vantage points during several trips to the Falls. He then worked out the details and created the painting in his studio in New York. Upon its completion, Church exhibited the painting at Williams, Stevens, Williams, and Company in New York. It was a special one-picture exhibition, and viewers were charged twenty-five cents to view the painting. Due to the success of "The Andes of Ecuador," the artist knew he was capable of creating major works that could stand on their own. Furthermore, not only did he receive a portion of the admissions, but also monies generated from prints and publications on the painting. "Niagara" was Church’s first venture into the genre known as the “Great Picture,” – individual works that were conceived for individual exhibition.

Niagara Falls had been painted numerous times by many artists, albeit not successfully. Church’s depiction of the painting was successful because he captured their appearance with extraordinary reality. One viewer was reported to say the only thing missing was the roar of the water. Furthermore, while Church had sketched multiple vantage points, he chose to depict the scene from Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side. He expanded the field of vision and adjusted the perspective so that both the near and far sides of the falls come into sight. The most dramatic effect was eliminating the foreground and removing any barrier between the viewer and the water itself.

In 1857, Church returned to the Andes with the idea of creating another great South American landscape. This time, Church traveled with French chronicler Louis Remy Mignot, and the two men sought out the mountain peaks of Cotopaxi, Pichincha, Cayambe, Sangay, and Chimborazo. Upon his return to New York, the artist immediately went to work on another mountain landscape, and in 1859, unveiled "Heart of the Andes" (Metropolitan Museum of Art). This time, Church’s depiction of the Andes was lush and green, characteristic of a new Eden. Its size is an astonishing 66 1/8 x119 inches (5 x 9 feet). A waterfall cuts through the foreground of the painting, and on a trail of a bluff overlooking the water stands a tall white cross with two people before it. Like "Niagara," "Heart of the Andes" was a one picture exhibition. The painting was placed in an elaborate dark wooden structure adorned with parted draperies and surrounded by plants Church had brought back from South America. The experience was meant to suggest that the viewer was actually standing where they had a view of the Andes themselves.

In 1859, Church, along with the Reverend Louis Legrand Noble chartered a 65-ton schooner out of Newfoundland to “chase” icebergs. The result was "The Icebergs of 1861," now at the Dallas Museum of Art.(10) "Cotopaxi" (1861, Detroit Institute of Arts) followed "The Icebergs" with its magnificent vista and volcanic eruption that clouds the expansive landscape. Church continued to create enormous masterpieces of American landscape throughout the 1860s and 1870s. In 1867, along with his wife and newborn child, Church embarked on an eighteenth-month tour of Europe and the Near East which produced works such as "The Parthenon" (1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art), "El Khasne, Petra" (1874, Olana State Historic Site), and "Syria by the Sea" (1873, Detroit Institute of Arts). Church and his family returned to New York in 1869, and the artist immediately plunged into designing and building a new house on property in the Hudson River Valley, which he named Olana.

During the 1870s, Church continued to maintain a studio in New York, but he was primarily occupied at Olana, drawing, sketching, painting, and overseeing the construction of the house. He still found time to travel and paint, visiting the Carolinas and Mexico in the 1880s. Church painted only sporadically in his later years, after experiencing a dramatic decline in the popularity of his works. His wife Isabel died in the spring of 1899, and he the following year, just after returning from a trip to Mexico.

(1) Quote taken from: Elaine Evans Dee, To Embrace the Universe: "Drawings by Frederic Edwin Church" (New York: Hudson River Museum, 1984): 9. This biography is adapted from Franklin Kelly’s "Fredric Edwin Church" (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1989).

(2) Theodore Winthrop, "A Companion to the Heart of the Andes" (New York, 1859): 4, 6.

(3) See Henry T. Tuckerman, “Frederic Edwin Church,” The Galaxy 1, no. 5 (1866): 423-29.

(4) Kelly, 34.

(5) Ibid, 35.

(6) Ibid, 38.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid, 47.

(9) Ibid, 50.

(10) Several years ago, the painting was damaged by a disgruntled employee who ran a black ink pen across the stark white icebergs. Fortunately, conservators were able to remove the ink and restore it to its original condition. More recently, the Dallas Museum of Art held a special exhibition where they showed The Icebergs in a room by itself, in an attempt to recreate the ”Great Picture” exhibitions of the nineteenth century. The viewer was directed into the room by a red velvet carpet and red velvet ropes. The room itself was very dark and the painting was dramatically lit and draped with red velvet curtains. Rows of chairs lined the front of the painting, and it was amazing to see the awe in the viewers that was probably not unlike those at its original exhibition.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 2/2/04

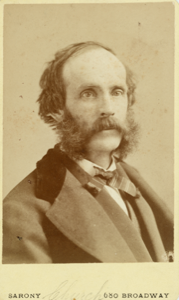

Image credit: Napoleon Sarony (American, born Canada, 1821–1896), Frederick Edwin Church, about 1868, albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, S/NPG.77.144, Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

American

(Hartford, Connecticut, 1826 - 1900, New York, New York)

“I enjoy immensely the effort to reproduce some of the marvelous atmospheric effects which are so frequent here. It is attempting the impossible still I like to make the effort and have the satisfaction of knowing that I make some progress.”

- Frederic Church, 1898, in a letter to Martin Johnson Heade in regard to Mexico (1)

In 1859, Theodore Winthrop (1828-1861), a writer and friend of Frederic Edwin Church, wrote that Church was “an artist who could appeal both to the tastes of those who sought merely to be entertained by art and to those who desired to be instructed and morally uplifted by it.” (2) Church was not only one of America’s great landscape artists, trained under Hudson River School legend Thomas Cole, but he was also a great showman. Known primarily for his enormous paintings of natural wonders such as the Andes, Niagara Falls, and icebergs, Church was the initiator of the “Great Picture,” a single-work exhibition. The artist provided his audience with extraordinary panoramas of parts of the world they had never seen before. His paintings not only supported early Transcendentalist ideas of God and nature, but they also encouraged the American notion of Manifest Destiny. With the economy recovering and on the rise from the depression in the 1830s, Americans increasingly wanted to know what lay beyond the safety and boundaries of their own communities. Church traveled the world in search of magnificent vistas to record on canvas, literally risking life and limb by climbing rock faces and treacherous paths to obtain sketches for his works. As a result, Church provided Americans with some of the nineteenth-century's most enchanting and awe-inspiring views of nature.

Frederic Edwin Church was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1826. The only son of a highly successful businessman, Church demonstrated talent for the arts at an early age. While not completely enthusiastic about his son’s endeavors, Church’s father agreed to support his studies. In Hartford, Church took drawing and oil painting lessons, and in 1844, at the age of eighteen, the young artist was apprenticed to Hudson River artist Thomas Cole (1801-1848). By then, Cole had been the most famous and most respected landscape painter in America for almost twenty years, and, he had never taken a student. Cole’s acceptance of Church was not only based on the young artist’s talent, but also heavy persuasion from Henry Wadsworth of Hartford, an important patron of the arts.

Cole was well known in the New York cultural circles, and although his relationships with leading patrons and connoisseurs were often uneasy, he understood the market for landscape painting better than anyone else. This was an important facet to Church’s early study. Art critic Henry Tuckerman noted in 1866 that Church’s enterprise in marketing was an important aspect in his successful career.(3)

Aside from business smarts, Cole also imparted to Church his theories of landscape painting. Cole felt that landscape paintings should have higher aims than merely recording the literal appearance of the natural world. Cole preferred painting compositions that were based on the study of nature, but did not attempt to recreate specific scenes. Cole believed that the ultimate purpose of the landscape painter was to create “a higher sense of landscape” that could “speak a language strong, moral, and imaginative.”(4) By the time Church joined Cole in the Catskills in 1844, Cole felt more strongly about his “mission” as an artist and that landscape painting should not be a mere imitation of nature.

One year after his apprenticeship with Cole (1844-46), Church settled in New York and took a studio in the Art Union building. He made his professional debut and sent two landscapes—"Twilight among the Mountains" (c. 1845, Olana State Historical Site) and "Hudson Scenery" (c. 1845, unlocated)—to the National Academy of Design. According to art historian Franklin Kelly, far more genius was displayed in Church’s "Hooker and Company Journeying through the Wilderness from Plymouth to Hartford, in 1636" (1846, Wadsworth Athenaeum). The landscape sets the stage for an important human event—the founding of Hartford—thus becoming an historical landscape painting. In the painting, Church’s precise and crisp handling of paint is unlike Cole’s manner, however, the elevated theme of the picture was clearly indebted to Cole’s theory. As Kelly explains, Church made “an early step toward adapting Cole’s ambitions for landscape to the evolving taste in America of the 1840s which favored more straightforward and factual paintings.” (5)

As his confidence grew, Church began to create more ambitious works based on precedents from Cole’s art. Several critics warned of mimesis, but Church’s precise manner of painting and his careful observation of the effects of light and shadow made his work different. Cole died in 1848 (leaving Asher B. Durand as the leading landscape painter), and the same year, Church painted a stirring tribute to his former master. "To the Memory of Cole" (1848, Des Moines Women’s Club) is a landscape based on the topography of the Catskills. The central focus is a white stone cross draped in a floral garland. The cross is the middle of the bucolic countryside, spotlighted by a shaft of sunlight. The rest of the landscape is overcast by billowing clouds that roll across the canvas. The clouds reflect the sunlight coming from outside of the painting; some have a pink and orange hue while others are stark white. Overall, the scene has an ethereal appearance heightened by the lack of human presence.(6) As Kelly notes, the landscape is punctuated by signs of change and tradition, as light alternates dark and leaves turn red amid sprigs of growth. The painting is a meditation on time and a “contrast of the fleeting quality of human life with the enduring permanence of nature.” (7) "To the Memory of Cole" is a touching memorial to a landscape master.

Another influence on Church and other landscape artists was English art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900). Ruskin, who’s "Modern Painters" was becoming known in America, favored a factual portrayal of nature in art. He noted how the beauties of the natural world were reflections of the higher order and plan of God. Ruskin encouraged landscape painters to express the deeper meanings of nature. From this point on, Church would travel to the furthest reaches of the earth in order to capture magnificent views of nature on canvas.

In 1849, Church was elected full academician at the National Academy of Design and was now solidly established in New York as an artist. A new confidence arose in his work and himself, and he began to sell a greater number of paintings. The National Academy of Design and the American Art Union provided Church (as well as other artists) opportunities to sell and exhibit to a number of collectors who wanted high quality landscapes.

At the end of the 1840s and into the early 1850s, Church primarily focused on New England landscapes. The Museum’s "American Landscape" is from this period. These smaller landscapes represented views of America that were meant to evoke the essence of an entire region of America. For example, New England Scenery (1851, George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield, Massachusetts) is an ideal scene bursting with images of God’s creations and abundance. A river dominates the foreground of the scene, which has attracted animals and humans alike—a house can be seen on a short bluff just above the river bed. A bridge with people crossing stretches across the foreground and lush trees and a mountainscape dominate the background. The painting didn’t represent once specific area in New England, but was made up of a number of specific characteristics of various parts of the northeast. This Zeuxian theory, whereby the most beautiful parts are selected and pieced together in order to create a harmonious whole, was characteristic of art practice since antiquity. This theory also echoed that of German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who was a strong influence on the direction Church’s art was about to take.

Humboldt, in "Cosmos: A Skretch of a Physical Description of the Universe" (1850), “attempted to synthesize existing scientific knowledge about the world into a grand theoretical system that could explain the underlying principles of the universe.” (8) Published before Darwin’s "The Origin of the Species" (1859), Humboldt provided the reader with a mix of rational science and the existence of a divine force for the world. The book confirmed Church’s beliefs and also included a section on landscape painting that encouraged artists to travel to parts unseen and record them on canvas. In 1853, Church would embark on a journey to South America with friend Cyrus W. Field, later promoter of Transatlantic Cable.

Church’s first South American paintings were compositionally similar to those of his North American works. The key difference was that within the work, Church depicted an exotic flora and fauna that was previously unseen by Eastern viewers, and provided a possible location for future expansion. Exhibited at the National Academy of Design in the fall of 1855, the works included: "The Cordilleras: Sunrise" (1854, Alexander Gallery, New York), "La Magdalena (Scene on the Magdalena)" (1854, National Academy of Design), "Tamaca Palms" (1854, Corcoran Gallery of Art, and "Tequendama Falls, near Bogota, New Granada" (1854, Cincinnati Art Museum). Their exhibition was a smashing success, but not nearly as breathtaking as "The Andes of Ecuador" (1855, Reynolda House, Museum of American Art).

"The Andes of Ecuador" was Church’s first large-scale painting, measuring 48 x 75 inches (4 x 6 feet). The artist chose to show it in Boston first, and when it came to the National Academy in 1857, the public and critics alike were astounded. The light in the painting was described as almost blinding the eye of the spectator, and another described it as “striking and bewildering.”(9) While the composition recalls earlier works, the landscape is opened up to the mountain chain with only a few trees to the left side of the canvas. Waterfalls are seen rushing throughout crevices in the mountain range. There are two Andean Indians underneath the trees at the left, and four llamas dot the center foreground of the painting. "The Andes of Ecuador" was a breakthrough for Church and with its inception, Church single-handedly changed American landscape painting. For the rest of his career, Church’s audience expected nothing but enormous and magnificent vistas.

Church’s next large project was "Niagara" (1857, Corcoran Gallery of Art). By the mid-nineteenth century, Niagara Falls was just developing as a tourist attraction, and the journey to reach the Falls was quite treacherous. Church, as by now had become customary, had made numerous sketches from multiple vantage points during several trips to the Falls. He then worked out the details and created the painting in his studio in New York. Upon its completion, Church exhibited the painting at Williams, Stevens, Williams, and Company in New York. It was a special one-picture exhibition, and viewers were charged twenty-five cents to view the painting. Due to the success of "The Andes of Ecuador," the artist knew he was capable of creating major works that could stand on their own. Furthermore, not only did he receive a portion of the admissions, but also monies generated from prints and publications on the painting. "Niagara" was Church’s first venture into the genre known as the “Great Picture,” – individual works that were conceived for individual exhibition.

Niagara Falls had been painted numerous times by many artists, albeit not successfully. Church’s depiction of the painting was successful because he captured their appearance with extraordinary reality. One viewer was reported to say the only thing missing was the roar of the water. Furthermore, while Church had sketched multiple vantage points, he chose to depict the scene from Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side. He expanded the field of vision and adjusted the perspective so that both the near and far sides of the falls come into sight. The most dramatic effect was eliminating the foreground and removing any barrier between the viewer and the water itself.

In 1857, Church returned to the Andes with the idea of creating another great South American landscape. This time, Church traveled with French chronicler Louis Remy Mignot, and the two men sought out the mountain peaks of Cotopaxi, Pichincha, Cayambe, Sangay, and Chimborazo. Upon his return to New York, the artist immediately went to work on another mountain landscape, and in 1859, unveiled "Heart of the Andes" (Metropolitan Museum of Art). This time, Church’s depiction of the Andes was lush and green, characteristic of a new Eden. Its size is an astonishing 66 1/8 x119 inches (5 x 9 feet). A waterfall cuts through the foreground of the painting, and on a trail of a bluff overlooking the water stands a tall white cross with two people before it. Like "Niagara," "Heart of the Andes" was a one picture exhibition. The painting was placed in an elaborate dark wooden structure adorned with parted draperies and surrounded by plants Church had brought back from South America. The experience was meant to suggest that the viewer was actually standing where they had a view of the Andes themselves.

In 1859, Church, along with the Reverend Louis Legrand Noble chartered a 65-ton schooner out of Newfoundland to “chase” icebergs. The result was "The Icebergs of 1861," now at the Dallas Museum of Art.(10) "Cotopaxi" (1861, Detroit Institute of Arts) followed "The Icebergs" with its magnificent vista and volcanic eruption that clouds the expansive landscape. Church continued to create enormous masterpieces of American landscape throughout the 1860s and 1870s. In 1867, along with his wife and newborn child, Church embarked on an eighteenth-month tour of Europe and the Near East which produced works such as "The Parthenon" (1871, Metropolitan Museum of Art), "El Khasne, Petra" (1874, Olana State Historic Site), and "Syria by the Sea" (1873, Detroit Institute of Arts). Church and his family returned to New York in 1869, and the artist immediately plunged into designing and building a new house on property in the Hudson River Valley, which he named Olana.

During the 1870s, Church continued to maintain a studio in New York, but he was primarily occupied at Olana, drawing, sketching, painting, and overseeing the construction of the house. He still found time to travel and paint, visiting the Carolinas and Mexico in the 1880s. Church painted only sporadically in his later years, after experiencing a dramatic decline in the popularity of his works. His wife Isabel died in the spring of 1899, and he the following year, just after returning from a trip to Mexico.

(1) Quote taken from: Elaine Evans Dee, To Embrace the Universe: "Drawings by Frederic Edwin Church" (New York: Hudson River Museum, 1984): 9. This biography is adapted from Franklin Kelly’s "Fredric Edwin Church" (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1989).

(2) Theodore Winthrop, "A Companion to the Heart of the Andes" (New York, 1859): 4, 6.

(3) See Henry T. Tuckerman, “Frederic Edwin Church,” The Galaxy 1, no. 5 (1866): 423-29.

(4) Kelly, 34.

(5) Ibid, 35.

(6) Ibid, 38.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Ibid, 47.

(9) Ibid, 50.

(10) Several years ago, the painting was damaged by a disgruntled employee who ran a black ink pen across the stark white icebergs. Fortunately, conservators were able to remove the ink and restore it to its original condition. More recently, the Dallas Museum of Art held a special exhibition where they showed The Icebergs in a room by itself, in an attempt to recreate the ”Great Picture” exhibitions of the nineteenth century. The viewer was directed into the room by a red velvet carpet and red velvet ropes. The room itself was very dark and the painting was dramatically lit and draped with red velvet curtains. Rows of chairs lined the front of the painting, and it was amazing to see the awe in the viewers that was probably not unlike those at its original exhibition.

- Letha Clair Robertson, 2/2/04

Image credit: Napoleon Sarony (American, born Canada, 1821–1896), Frederick Edwin Church, about 1868, albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, S/NPG.77.144, Photograph courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Artist Objects