William Christenberry

American

(Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1936 – 2016, Washington, D.C.)

To really know the South, and especially Alabama, one has to know the works of William Christenberry. Many artists have made art about the South, but Christenberry’s art is the living South—its land, people, and history—given tangible form in multiple media, most prominently photography and sculpture. Christenberry has thousands of stories that are based on his life and memories of the region, and one way or another, he will tell them all.

William Christenberry was born 5 November 1936 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and attended the University of Alabama where he obtained BFA and MA degrees. He was appointed an Instructor of Art at his alma mater in 1959 and taught until 1961, when he accepted a position to teach at Memphis State University and became Assistant and then Associate Professor of Art. He moved to Washington, D.C. in 1968, where he served as Associate and then Professor of Art at the Corcoran School of Art from 1968 until his retirement in 2006. He remained a working artist in Washington D.C. after his retirement, and died in 2016.

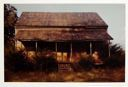

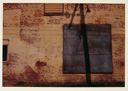

Growing up in Hale County, Christenberry developed a fascination with the landscape of Alabama and its vernacular architecture. Even after he firmly established himself in Washington, D.C., he maintained that Alabama was “where my heart is.” (1) The sun, earth, and architecture of Alabama inspired him throughout his career. He once said that he “empathize[s] with pure landscape.” On annual visits by car to his relatives, he responded to the Alabama landscape “year after year.” He had no affinity for prefab architecture or antebellum Southern mansions, but instead long gravitated towards Alabama’s old country stores and aging or abandoned tenant buildings —the “beauty of a given structure.” He stated “the things that have aged—that appealed to me more.” In his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and photographs, he captured images of those vernacular buildings of Alabama that are increasingly collapsing and disappearing. “All of my work," he once wrote, "whether painting, sculpture, or photography—deals with my affection for the place I am from, Alabama.” (2)

With distance, Christenberry developed the worldview and objectivity that allowed him to convey what is most important to him about his home state and the local communities of his childhood. Like the Southern Gothic writers such as William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Christenberry found splendor in the dissolution and change that time has visited upon the land and its inhabitants. He returned to Alabama in the summertime for more than thirty years to record these changes and to process the evolution of his own life and work.

On Christmas Day 1944 or 1945, Christenberry received a Kodak Brownie Holiday camera “from Santa Claus” and an enduring interest in capturing images of Hale County, his boyhood terrain, began. Initially he peopled his images with friends and family, using the camera to record family vacations and events in the 1940s and 50s. In the late 1950s he used photographs “as color studies for paintings.” (3) When in 1960 he came across the newly printed edition of James Agee’s "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" (1941; reprinted in 1960), which included Walker Evans’s photographs of sharecroppers in Hale County, Christenberry was encouraged to continue focusing on the landscape and architecture of Alabama as his subject. Both Agee’s words and Evans’s images had an impact on the artist: “Walker was a very meaningful person in my life, but don’t forget Agee…What Agee was doing in the written word was what I wanted to do visually.” (4) Evans’s straightforward photographs of ordinary roadside subjects inspired the burgeoning Christenberry. Evans encouraged him and said to him, “Young man, there is something about the way you use this little camera that makes it a perfect extension of your eye.” (5) He called Christenberry’s Brownie photographs “perfect little poems.” (6)

Though Christenberry maintained that he never took a lesson in photography and does not develop the images himself, he has become an esteemed master in the medium. Photography quickly became a crucial part of his artistic process. The images that the Brownie Holiday camera produces are small—3 x 5 inches, postcard dimension, “no fancy thing” as Christenberry noted, but they endow a “straightforwardness and honesty to the resulting image” which Christenberry appreciated. The artist declared in 2001: “ I still feel very strongly that those little Brownie snapshots are as honest a statement as I’ve ever made in my work, because I wasn’t thinking about making art. I was photographing things that caught my eye.” (7)

In his photographs, he wanted to “record something beautiful and interesting” and to create “a record of what’s not there anymore.” The photographs encapsulate what the artist termed the “aesthetics of the aging process.” They are not intended to be overly sentimental, but rather are “attached to place.”

More and more the Brownie photographs, simple objects from a simple camera, intersected with other aspects of his art. They informed his sculptural creations and paintings and became increasingly on “equal par with painting and sculpture”. As one scholar noted, “he came to realize the inherent value of his photographs and their haunting, ephemeral evocation of a particular place in time.” Because he often returned to photograph the same buildings and landscapes, gradually he created series or “grids” of photographs, which, as one scholar described, create a “cinematic” effect “like a long time-lapse movie slowed to individual frames at particular years.” (8) Art objects in their own right, the artist began to frame and exhibit the photographs.

The first major exhibition of his photographic work was held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1973. Up until that time, Christenberry noted, color photographs “had been frowned upon by the world of fine art photography, even by Walker Evans himself.” (9) But the exhibition helped to “foster the use and acceptance of such small-scale, commercially printed color photographs as viable fine art objects.” The exhibition and his photographs attracted the attention of a bevy of important photographers, including Lee Friedlander, Walker Evans, and William Eggleston, who soon joined him on his trips south. Great Southern novelist Walker Percy praised Christenberry’s photographs, calling them “poetic evocations of a haunted countryside.” (10)

While Christenberry is still best known as a photographer, his artwork over four decades took multiple forms, including painting, drawing, sculpture and assemblage. In each medium he mined the conceptual wellspring that is his family history, his regional roots, and his desire to document the passage of time as marked by material culture. Inspired during his college years and early professional life by the Abstract Expressionists and the masters of Dada and Surrealism, Christenberry originally created large-scale painted canvases. (11). In 1974, he began the process of re-interpreting a number of his photographic subjects as sculpture, “re-casting those images on a different plane, translating them back, as it were, into three dimensions.” (12) . Beginning in 1962, Christenberry began producing works of art that address the social and historical phenomenon of the Ku Klux Klan in the American South. As an organization utilizing intimidation and terrorist tactics, the Klan and its philosophies represented for Christenberry the darker side of his personal and regional heritage. (13)

A large segment of his work embraced a simpler, more elemental form of creating art through assemblage using discarded and found objects. The first was "Southern Monument "(1979), commissioned by the General Services Administration Art-in-Architecture program for the Federal Building in Jackson, Mississippi. The elements favored by Christenberry speak to a shifting culture—old, weather-beaten, metal advertising signs, car license plates, painted and rusted metal scraps tying together remnants of the past. In 1985 Christenberry built "Alabama Wall", a square construction now owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Christenberry long embraced the role of teacher, becoming an instructor at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1968, and participating in artist-in-residence programs throughout his career. His work remains widely exhibited in commercial galleries, contemporary art centers, and in museums both in the United States and in Europe.

(1) Interview with the artist, 1 October 2008, at the artist’s home/studio, Washington, D.C., by Margaret Burgess. Unless otherwise attributed, all quotes are by the artist from this interview.

(2) Terry Tempest Williams, ed., In Response to Place (Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2004), p. 58.

(3) "1992 Montgomery Biennial: In/Outsiders from the American South," (Montgomery, AL: Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1992), n. p.

(4) Philip Gefter, “Southern Exposures: Past and Present Through the Lens of William Christenberry,” New York Times, 2 July 2006, Art.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Anne Timpano, William Christenberry. Architecture/Archetype (Cincinnati, Ohio: Dorothy W. and C. Lawson Read, Jr., Gallery, 2001), p. 7.

(8) Gefter, op.cit

(9) Timpano, p. 7.

(10) R.H. Cravens, "William Christenberry. Southern Photographs," (Millerton: Aperture, 1983), p. 7.

(11) Susanne Lange, "William Christengerry," (Dusseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2002), p. 28

(12) Lange, p. 30

(13) Lange, p. 84, Walter Hopps, et. al, "William Christenberry," (New York: Aperture Foundation,2006), p. 194.

Margaret Burgess

December, 2008

American

(Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1936 – 2016, Washington, D.C.)

To really know the South, and especially Alabama, one has to know the works of William Christenberry. Many artists have made art about the South, but Christenberry’s art is the living South—its land, people, and history—given tangible form in multiple media, most prominently photography and sculpture. Christenberry has thousands of stories that are based on his life and memories of the region, and one way or another, he will tell them all.

William Christenberry was born 5 November 1936 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and attended the University of Alabama where he obtained BFA and MA degrees. He was appointed an Instructor of Art at his alma mater in 1959 and taught until 1961, when he accepted a position to teach at Memphis State University and became Assistant and then Associate Professor of Art. He moved to Washington, D.C. in 1968, where he served as Associate and then Professor of Art at the Corcoran School of Art from 1968 until his retirement in 2006. He remained a working artist in Washington D.C. after his retirement, and died in 2016.

Growing up in Hale County, Christenberry developed a fascination with the landscape of Alabama and its vernacular architecture. Even after he firmly established himself in Washington, D.C., he maintained that Alabama was “where my heart is.” (1) The sun, earth, and architecture of Alabama inspired him throughout his career. He once said that he “empathize[s] with pure landscape.” On annual visits by car to his relatives, he responded to the Alabama landscape “year after year.” He had no affinity for prefab architecture or antebellum Southern mansions, but instead long gravitated towards Alabama’s old country stores and aging or abandoned tenant buildings —the “beauty of a given structure.” He stated “the things that have aged—that appealed to me more.” In his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and photographs, he captured images of those vernacular buildings of Alabama that are increasingly collapsing and disappearing. “All of my work," he once wrote, "whether painting, sculpture, or photography—deals with my affection for the place I am from, Alabama.” (2)

With distance, Christenberry developed the worldview and objectivity that allowed him to convey what is most important to him about his home state and the local communities of his childhood. Like the Southern Gothic writers such as William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor, Christenberry found splendor in the dissolution and change that time has visited upon the land and its inhabitants. He returned to Alabama in the summertime for more than thirty years to record these changes and to process the evolution of his own life and work.

On Christmas Day 1944 or 1945, Christenberry received a Kodak Brownie Holiday camera “from Santa Claus” and an enduring interest in capturing images of Hale County, his boyhood terrain, began. Initially he peopled his images with friends and family, using the camera to record family vacations and events in the 1940s and 50s. In the late 1950s he used photographs “as color studies for paintings.” (3) When in 1960 he came across the newly printed edition of James Agee’s "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" (1941; reprinted in 1960), which included Walker Evans’s photographs of sharecroppers in Hale County, Christenberry was encouraged to continue focusing on the landscape and architecture of Alabama as his subject. Both Agee’s words and Evans’s images had an impact on the artist: “Walker was a very meaningful person in my life, but don’t forget Agee…What Agee was doing in the written word was what I wanted to do visually.” (4) Evans’s straightforward photographs of ordinary roadside subjects inspired the burgeoning Christenberry. Evans encouraged him and said to him, “Young man, there is something about the way you use this little camera that makes it a perfect extension of your eye.” (5) He called Christenberry’s Brownie photographs “perfect little poems.” (6)

Though Christenberry maintained that he never took a lesson in photography and does not develop the images himself, he has become an esteemed master in the medium. Photography quickly became a crucial part of his artistic process. The images that the Brownie Holiday camera produces are small—3 x 5 inches, postcard dimension, “no fancy thing” as Christenberry noted, but they endow a “straightforwardness and honesty to the resulting image” which Christenberry appreciated. The artist declared in 2001: “ I still feel very strongly that those little Brownie snapshots are as honest a statement as I’ve ever made in my work, because I wasn’t thinking about making art. I was photographing things that caught my eye.” (7)

In his photographs, he wanted to “record something beautiful and interesting” and to create “a record of what’s not there anymore.” The photographs encapsulate what the artist termed the “aesthetics of the aging process.” They are not intended to be overly sentimental, but rather are “attached to place.”

More and more the Brownie photographs, simple objects from a simple camera, intersected with other aspects of his art. They informed his sculptural creations and paintings and became increasingly on “equal par with painting and sculpture”. As one scholar noted, “he came to realize the inherent value of his photographs and their haunting, ephemeral evocation of a particular place in time.” Because he often returned to photograph the same buildings and landscapes, gradually he created series or “grids” of photographs, which, as one scholar described, create a “cinematic” effect “like a long time-lapse movie slowed to individual frames at particular years.” (8) Art objects in their own right, the artist began to frame and exhibit the photographs.

The first major exhibition of his photographic work was held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1973. Up until that time, Christenberry noted, color photographs “had been frowned upon by the world of fine art photography, even by Walker Evans himself.” (9) But the exhibition helped to “foster the use and acceptance of such small-scale, commercially printed color photographs as viable fine art objects.” The exhibition and his photographs attracted the attention of a bevy of important photographers, including Lee Friedlander, Walker Evans, and William Eggleston, who soon joined him on his trips south. Great Southern novelist Walker Percy praised Christenberry’s photographs, calling them “poetic evocations of a haunted countryside.” (10)

While Christenberry is still best known as a photographer, his artwork over four decades took multiple forms, including painting, drawing, sculpture and assemblage. In each medium he mined the conceptual wellspring that is his family history, his regional roots, and his desire to document the passage of time as marked by material culture. Inspired during his college years and early professional life by the Abstract Expressionists and the masters of Dada and Surrealism, Christenberry originally created large-scale painted canvases. (11). In 1974, he began the process of re-interpreting a number of his photographic subjects as sculpture, “re-casting those images on a different plane, translating them back, as it were, into three dimensions.” (12) . Beginning in 1962, Christenberry began producing works of art that address the social and historical phenomenon of the Ku Klux Klan in the American South. As an organization utilizing intimidation and terrorist tactics, the Klan and its philosophies represented for Christenberry the darker side of his personal and regional heritage. (13)

A large segment of his work embraced a simpler, more elemental form of creating art through assemblage using discarded and found objects. The first was "Southern Monument "(1979), commissioned by the General Services Administration Art-in-Architecture program for the Federal Building in Jackson, Mississippi. The elements favored by Christenberry speak to a shifting culture—old, weather-beaten, metal advertising signs, car license plates, painted and rusted metal scraps tying together remnants of the past. In 1985 Christenberry built "Alabama Wall", a square construction now owned by the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Christenberry long embraced the role of teacher, becoming an instructor at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1968, and participating in artist-in-residence programs throughout his career. His work remains widely exhibited in commercial galleries, contemporary art centers, and in museums both in the United States and in Europe.

(1) Interview with the artist, 1 October 2008, at the artist’s home/studio, Washington, D.C., by Margaret Burgess. Unless otherwise attributed, all quotes are by the artist from this interview.

(2) Terry Tempest Williams, ed., In Response to Place (Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2004), p. 58.

(3) "1992 Montgomery Biennial: In/Outsiders from the American South," (Montgomery, AL: Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 1992), n. p.

(4) Philip Gefter, “Southern Exposures: Past and Present Through the Lens of William Christenberry,” New York Times, 2 July 2006, Art.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Anne Timpano, William Christenberry. Architecture/Archetype (Cincinnati, Ohio: Dorothy W. and C. Lawson Read, Jr., Gallery, 2001), p. 7.

(8) Gefter, op.cit

(9) Timpano, p. 7.

(10) R.H. Cravens, "William Christenberry. Southern Photographs," (Millerton: Aperture, 1983), p. 7.

(11) Susanne Lange, "William Christengerry," (Dusseldorf: Richter Verlag, 2002), p. 28

(12) Lange, p. 30

(13) Lange, p. 84, Walter Hopps, et. al, "William Christenberry," (New York: Aperture Foundation,2006), p. 194.

Margaret Burgess

December, 2008

Artist Objects

![Image of Church Across Early Cotton—Pickinsville [sic], Alabama](/media/Thumbnails/1980/1980.0001.0003.or1.png)

![Image of Abandoned House, Pickinsville [sic], Alabama](/media/Thumbnails/2004/2004.0015.0001.or1.png)