Edward Hopper

American

(Nyack, New York, 1882 - 1967, New York, New York)

In an era of American art stylistically dominated by abstraction, the artist most frequently associated with realism is Edward Hopper. Although he firmly resisted categorization as an American Scene painter, Hopper has come to be known as the most important of those mid-century realists whose un-idealized subjects derived from American society and culture.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York on July 22, 1882. Located on the Hudson River, Nyack was a center for boat building, and the artist's love of the water and related subjects can be traced to his youth in this river town. By the age of 17 he had decided upon a career as an artist, but, to insure some level of financial security, was urged by his parents to train as an illustrator. He began at a commercial art school in New York (the Correspondence School of Illustration), and then transferred to the New York School of Art (also called the Chase School, for its founder William Merritt Chase). After brief study with Chase, he studied with painters Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller for about five years (1900 to 1906), and then traveled to Europe, spending about nineteen months abroad between 1906 and 1910.

Until about 1925 Hopper supported himself through illustration and commercial art, a profession he heartily disliked. He had his first one-person exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club in January of 1920, and his earliest critical success was with the etchings that he made between 1915 and 1923. He produced some sixty plates in etching and drypoint in those years, winning two prizes in 1923. His prints sold well and, beginning in 1923, his watercolors achieved sufficient recognition to allow him to cease working as an illustrator and devote full time to painting. In 1924, when he was almost forty-two years old, he married Josephine Verstille Nivison, who had also been a student of Henri. They had no children, and divided their time between an apartment in New York at 3 Washington Square North, and, after 1930, summers at South Truro on Cape Cod. The Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery became Hopper’s dealer in 1924 and Rehn, or his associate John Clancy, represented Hopper for the remainder of his life.

Hopper’s work departed from the realm of his teacher Robert Henri (and that of the other so-called Ashcan School artists) in its honest, steadfast portrayal of everyday American life and the fabric of a culture that had evolved from the American land. He avoided both the sentimental and the heroic, and focused instead on the transition from a rural, agrarian economy to a burgeoning industrial society—long established country roads and houses with telephone poles rising incongruously from their borders conveyed the spirit of his work. His was an art of transformation. “In a basically affirmative spirit he built his art out of the common American scene, in all its meanness and largeness, its ugliness and its unintended beauty….This robust acceptance gave his portrait of America a strength and authenticity that were new notes in our art…and added to the depth and intensity of its emotional content.” (1)

The subjective element of Hopper’s art was based on his admiration of America and the character of its people. His compositions generally centered not on the people themselves, but on the land and the built environment—from the massive, monumental architecture of the urban landscape, to the small town with its hodgepodge of architectural styles. Contemporaries found his choice of old houses, dilapidated industrial sites and cityscapes very curious. (2) His practice was to select subjects that would otherwise go unnoticed and interpret them as reflections not just of modern society, but a modern state of mind. He simplified the formal elements, which are strongly defined by light and shadow. The quality of the light varies to establish the mood and character of the scene.

There are a number of formulas and themes that are found repeatedly in Hopper’s work. Chief among the compositional devices are a tendency to use strong horizontals punctuated by slender vertical lines and bold diagonals that form the base of a composition. A sense of continuation beyond the picture plane is often achieved through low horizon lines and sweeping vistas and skies.

“Hopper was that rare phenomenon, a genuinely modest man.” (3) His deliberate, meticulous working methods reflected his personal reticence. He was quiet, and highly self critical, at times finding the process of creation to be difficult and laborious. Hopper varied his working method depending on the medium. In most cases, he was deliberate in his conception and execution of oil paintings, beginning with observations from life and then preparatory drawings in which he distilled and developed an idea. Many elements might be selected, drawn and finally combined within a composition. In watercolor, however, he usually painted directly from life, a process that required a tempered form of spontaneity that was generally at odds with his own character. Once he achieved success in that medium, however, critics compared him specifically to the nineteenth-century master of American watercolor painting Winslow Homer. Like Hopper, Homer established a career as an illustrator before he turned to watercolor painting, and he also chose to paint subjects associated with the northeast coast. It was the accomplishments of Homer, and his contemporary John Singer Sargent, that created the climate for a greater appreciation of watercolor painting among collectors and museums in the United States just as Hopper matured as a watercolorist in the 1920s. (4)

Hopper’s reputation as an artist steadily increased over the course of his career. He received his first retrospective exhibition in 1933 at the Museum of Modern Art, and a second in 1950 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In December of 1956 he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, confirming his reputation as one of the most important artists in the history of American painting. A third, major retrospective followed in 1964 and generated a sizable body of critical assessment of his work. At this point in his career he began to be considered within the context of the contemporary abstract painters who surrounded him. While he never embraced the essential philosophy of abstraction (he joined an association of artists called Reality in 1952 that proclaimed, “all art is an expression of human experience”), the simplified geometry of his forms and the disquieting nature of his themes linked him with modern painters in the eyes of critics. When he died on May 15, 1967 at the age of eighty-four, Hopper was already considered an American master.

(1) Whitney Museum of American Art, Edward Hopper: Selections from the Hopper Bequest, Introduction by Lloyd Goodrich. (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1971), p. 8.

(2) Garnett McCoy, "The Best Things of Their Kind Since Homer," Archives of American Art Bulletin, 7, (July-October, 1967), p. 12.

(3) Whitney Museum...p. 12.

(4) Virginia Mecklenburg, Edward Hopper: The Watercolors, (New York and Washington: W.W. Norton & Company in association with the National Museum of American Art, 1999), p. 3-4.

Margaret Lynne Ausfeld

Curator of Paintings and Sculpture

22 December 2003

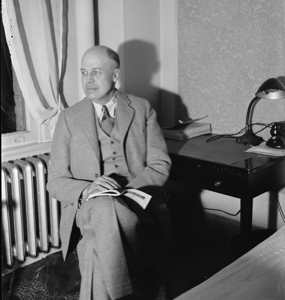

Image credit: Harris & Ewing (active 1900s-1940s), Edward Hopper, New York Artist, 1937, glass negative, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., [LC-H22- D-1194]

American

(Nyack, New York, 1882 - 1967, New York, New York)

In an era of American art stylistically dominated by abstraction, the artist most frequently associated with realism is Edward Hopper. Although he firmly resisted categorization as an American Scene painter, Hopper has come to be known as the most important of those mid-century realists whose un-idealized subjects derived from American society and culture.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York on July 22, 1882. Located on the Hudson River, Nyack was a center for boat building, and the artist's love of the water and related subjects can be traced to his youth in this river town. By the age of 17 he had decided upon a career as an artist, but, to insure some level of financial security, was urged by his parents to train as an illustrator. He began at a commercial art school in New York (the Correspondence School of Illustration), and then transferred to the New York School of Art (also called the Chase School, for its founder William Merritt Chase). After brief study with Chase, he studied with painters Robert Henri and Kenneth Hayes Miller for about five years (1900 to 1906), and then traveled to Europe, spending about nineteen months abroad between 1906 and 1910.

Until about 1925 Hopper supported himself through illustration and commercial art, a profession he heartily disliked. He had his first one-person exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club in January of 1920, and his earliest critical success was with the etchings that he made between 1915 and 1923. He produced some sixty plates in etching and drypoint in those years, winning two prizes in 1923. His prints sold well and, beginning in 1923, his watercolors achieved sufficient recognition to allow him to cease working as an illustrator and devote full time to painting. In 1924, when he was almost forty-two years old, he married Josephine Verstille Nivison, who had also been a student of Henri. They had no children, and divided their time between an apartment in New York at 3 Washington Square North, and, after 1930, summers at South Truro on Cape Cod. The Frank K. M. Rehn Gallery became Hopper’s dealer in 1924 and Rehn, or his associate John Clancy, represented Hopper for the remainder of his life.

Hopper’s work departed from the realm of his teacher Robert Henri (and that of the other so-called Ashcan School artists) in its honest, steadfast portrayal of everyday American life and the fabric of a culture that had evolved from the American land. He avoided both the sentimental and the heroic, and focused instead on the transition from a rural, agrarian economy to a burgeoning industrial society—long established country roads and houses with telephone poles rising incongruously from their borders conveyed the spirit of his work. His was an art of transformation. “In a basically affirmative spirit he built his art out of the common American scene, in all its meanness and largeness, its ugliness and its unintended beauty….This robust acceptance gave his portrait of America a strength and authenticity that were new notes in our art…and added to the depth and intensity of its emotional content.” (1)

The subjective element of Hopper’s art was based on his admiration of America and the character of its people. His compositions generally centered not on the people themselves, but on the land and the built environment—from the massive, monumental architecture of the urban landscape, to the small town with its hodgepodge of architectural styles. Contemporaries found his choice of old houses, dilapidated industrial sites and cityscapes very curious. (2) His practice was to select subjects that would otherwise go unnoticed and interpret them as reflections not just of modern society, but a modern state of mind. He simplified the formal elements, which are strongly defined by light and shadow. The quality of the light varies to establish the mood and character of the scene.

There are a number of formulas and themes that are found repeatedly in Hopper’s work. Chief among the compositional devices are a tendency to use strong horizontals punctuated by slender vertical lines and bold diagonals that form the base of a composition. A sense of continuation beyond the picture plane is often achieved through low horizon lines and sweeping vistas and skies.

“Hopper was that rare phenomenon, a genuinely modest man.” (3) His deliberate, meticulous working methods reflected his personal reticence. He was quiet, and highly self critical, at times finding the process of creation to be difficult and laborious. Hopper varied his working method depending on the medium. In most cases, he was deliberate in his conception and execution of oil paintings, beginning with observations from life and then preparatory drawings in which he distilled and developed an idea. Many elements might be selected, drawn and finally combined within a composition. In watercolor, however, he usually painted directly from life, a process that required a tempered form of spontaneity that was generally at odds with his own character. Once he achieved success in that medium, however, critics compared him specifically to the nineteenth-century master of American watercolor painting Winslow Homer. Like Hopper, Homer established a career as an illustrator before he turned to watercolor painting, and he also chose to paint subjects associated with the northeast coast. It was the accomplishments of Homer, and his contemporary John Singer Sargent, that created the climate for a greater appreciation of watercolor painting among collectors and museums in the United States just as Hopper matured as a watercolorist in the 1920s. (4)

Hopper’s reputation as an artist steadily increased over the course of his career. He received his first retrospective exhibition in 1933 at the Museum of Modern Art, and a second in 1950 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In December of 1956 he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, confirming his reputation as one of the most important artists in the history of American painting. A third, major retrospective followed in 1964 and generated a sizable body of critical assessment of his work. At this point in his career he began to be considered within the context of the contemporary abstract painters who surrounded him. While he never embraced the essential philosophy of abstraction (he joined an association of artists called Reality in 1952 that proclaimed, “all art is an expression of human experience”), the simplified geometry of his forms and the disquieting nature of his themes linked him with modern painters in the eyes of critics. When he died on May 15, 1967 at the age of eighty-four, Hopper was already considered an American master.

(1) Whitney Museum of American Art, Edward Hopper: Selections from the Hopper Bequest, Introduction by Lloyd Goodrich. (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1971), p. 8.

(2) Garnett McCoy, "The Best Things of Their Kind Since Homer," Archives of American Art Bulletin, 7, (July-October, 1967), p. 12.

(3) Whitney Museum...p. 12.

(4) Virginia Mecklenburg, Edward Hopper: The Watercolors, (New York and Washington: W.W. Norton & Company in association with the National Museum of American Art, 1999), p. 3-4.

Margaret Lynne Ausfeld

Curator of Paintings and Sculpture

22 December 2003

Image credit: Harris & Ewing (active 1900s-1940s), Edward Hopper, New York Artist, 1937, glass negative, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., [LC-H22- D-1194]