James Abbott McNeill Whistler

American

(Lowell, Massachusetts, 1834 - 1903, London, England)

James McNeill Whistler was a painter, printmaker, and theoretician whose work is recognized today as an important achievement in nineteenth-century art. Aesthetically, however, Whistler always pursued his own single-minded vision of art rather than adopting one of the mainstream approaches then in vogue. Although the gregarious painter both craved and received enormous attention in England, France, and the United States during his lifetime, his unique development and achievement has placed him outside the accepted narrative of the history of art.

Americans claim Whistler because he was born in Massachusetts to American parents, and because he always retained his identification as an American, as an outsider living in a hostile British artistic environment. (1) Yet, equally, he might be claimed by France, where he formed his aesthetic opinions in the cauldron of French theory at midcentury and where his most significant training occurred. Or yet again, he might be (and often is) included in a survey of nineteenth-century art in Britain, where he lived for the overwhelming majority of his adult life. It is prudent to recall that Whistler spent only fifteen of his first twenty-one years in the United States, never returning to this side of the Atlantic after attaining his majority.

Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts on July 11, 1834, a fact he regularly attempted to obscure for much of the rest of his life. (2) George Washington Whistler, the artist’s father, was a civil engineer in the United States Army. In 1842, Major Whistler accepted the invitation of Nicholas I, czar of Russia, to design and build the first railway line from Moscow to St. Petersburg. The family followed the Major to Russia a year later, and the young James spent much of the next six years in St. Petersburg, taking his first art lessons at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. His hosts at the Russian court, a cultivated and cosmopolitan circle in which French was spoken, regarded James as the child of an honored visitor. He appears to have been shaped in some ways by his experience during these formative years—he received a broad education, became familiar with art, and although often the center of attention, became accustomed to thinking of himself as an outsider. He also had the opportunity to spend time in London with his brother-in-law Francis Seymour Haden, a doctor, an amateur etcher, and an astute collector.

The death of Major Whistler in April 1849 necessitated the family’s relocation to Pomfret, Connecticut. Two years later, the young artist followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, then under Colonel Robert E. Lee. Whistler excelled at drawing in classes taught by Robert W. Weir but exhibited a notable lack of discipline in his other coursework, which led to his dismissal from the academy in June 1854. After a short apprenticeship at Thomas Winan’s locomotive works in Baltimore, he arrived in Washington in November with an appointment to the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. He lasted there for less than two months, making it just into the New Year before being summarily dismissed for bad work habits and lack of attendance. Though his period at the Geodetic Survey was brief, it proved crucial to his later development, since this is where he experienced his first serious exposure to etching learned to etch. In July 1855, Whistler turned twenty-one, at which point he began receiving an income from his father’s estate, and soon thereafter moved to Paris to study art, leaving the United States never to return.

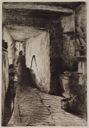

The problem of categorization that plagues Whistler as a painter is not considered as serious a detriment in appreciating his career as a printmaker. Influential writer Charles-Pierre Baudelaire commended Whistler’s talent in that realm in 1862. “Just the other day a young American artist, M. Whistler, was showing at the Galerie Martinet a set of etchings, as subtle and lively as improvisation and inspiration, representing the banks of the Thames, wonderful tangles of rigging, yardarms and rope; farragos of fog, furnaces and corkscrews of smoke; the profound and intricate poetry of a vast capital.” (3) Four years prior, in spring 1859, Whistler’s prints had won acceptance at the Salon in Paris and at the Royal Academy in London. In the 1860s, even when Whistler’s paintings met with mixed reception, and regular rejection from both the Academy and the Salon, critics simultaneously acknowledged his strengths as a draughtsman and a consummate etcher.

From the outset of his career, Whistler conceived of much of his graphic work in terms of sets, to be presented and marketed as groups of related images, inspired by both the vogue for Japanese woodblock prints, and the recognized master of the revival of etching, Charles Meryon. His earliest important prints were included in “Twelve Etchings from Nature” of 1858, generally referred to as the “French Set”. He was planning a second set at the time of his immigration to England, although his “Sixteen Etchings of Scenes of the Thames,” referred to as the Thames Set, was not issued until 1871. Later, he went to Venice in September 1879 with the explicit commission to render a set of twelve etchings of the city in a brief three month period. That three-month period stretched to fourteen, during which he executed a sufficient number to publish both the original dozen, the “First Venice Set”, and a second series of mostly Venetian scenes, the “Second Venice Set”. A decade later, in 1889, he traveled to Amsterdam, the city of his artistic idol Rembrandt van Rijn, where he planned and executed the Amsterdam Set.

Whistler moved to Chelsea in 1863 and lived there, with rare breaks in Paris and Venice, for the rest of his life. Though many of the paintings of the 1860s reflect these new surroundings, the artist largely abandoned etching during the second half of the 1860s. Whistler worked episodically on etching and drypoint through the 1870s, preoccupied as he was with painting. The lithographs Whistler executed in 1878 are far more atmospheric than anything he had yet attempted in etching and drypoint. This had to do with the expressive vocabulary inherent in the lithographic process, one that allowed the artist to conceive and work the design in tone rather than line. Thomas Way, the printer who taught Whistler lithography, arranged for Whistler to draw and paint on a stone while floating on a barge on the Thames in the dock area of East London where Whistler had first etched twenty years before. (4) His final two great print series were created over a fourteen month period in Venice.

The story of Whistler in Venice is the centerpiece to the Whistler legend, a tale of fall from grace, exile, and triumphant return. Whistler made a calculated decision to bring suit against the critic John Ruskin for libel, resulting in perhaps the most celebrated trial in the history of art, Whistler v. Ruskin. Ruskin had condemned Whistler’s work in a review that appeared in the July 1877 issue of his Fors Clavigera. “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” he wrote. (5) Although the jury found in favor of Whistler, agreeing that Ruskin had committed libel, they awarded him only one farthing (a quarter of a penny), rather than the £1,000 that he had sought in the action. Interpreting the jury’s award as a strong reproach to Whistler for having brought the matter to trial, the judge directed that the two sides each absorb their own expenses. The decision led to Whistler’s bankruptcy in May 1879. By the summer financial insolvency and a lack of new patronage resulting from adverse publicity left Whistler reeling; he accepted a commission from a commercial gallery in London, the Fine Art Society, to etch a series of prints of Venice for December holiday sales.

He wrestled with the subject matter of Venice, overwhelmed by the remarkable visual riches of the city. He wanted to develop his own approach to the city, one that would distinguish his work from the anecdotal sentimentality of established Victorian imagery. His achievement relied in part on this original conception of a Venice that was best known to contemporary Venetians—the long vistas, the back alleys, the quiet canals and idiosyncratic bridges that cross them, and the isolated squares of the everyday life of the city. The artist rendered few images of the usual sights, the Piazza San Marco, the Basilica, and the Grand Canal. The artist subsequently remained in Venice for fourteen months, during which he executed more than fifty prints, a handful of paintings, and approximately one hundred pastels. The etchings are at the core of Whistler’s Venetian achievement. Upon his return to England, the exhibitions of his Venetian etchings and pastels reestablished his artistic reputation, and provided a turning point in his career.

On August 11, 1888, Whistler married Beatrice Godwin, the affluent widow of his friend and collaborator, architect E. W. Godwin. In September of the following year, Whistler and Trixie spent two months in Amsterdam where the artist drew ten plates that he hoped to publish as a set through the Fine Art Society. However, since he had never completed the editions of the First Venice Set of 1880, the firm declined his offer.

In an article of March 11, 1890, in the Pall Mall Budget, he is recorded as having first displayed and discussed the individual Amsterdam etchings, and then to have summed up his etching career in this way:

“I divide myself into three periods,” he says, being in his most serious and sensible mood. “First you see me at work on the Thames,” producing one of the famous series. “Now, there you have the crude and hard detail of the beginner. So far, so good. There, you see, all is sacrificed to exactitude of outline. Presently, and almost unconsciously, I begin to criticize myself, and to feel the craving of the artist for form and colour. The result was the second stage, which my enemies call The Inchoate, and I call Impressionism. The third stage I have shown you. In that I have endeavoured to combine stages one and two. You have the elaboration of the first stage and the quality of the second.” (6)

Whistler died on July 17, 1903 in London.

Text based upon Eric Denker, “Whistler and the Search for Printed Tone,” Fleeting Impressions: Prints by James McNeill Whistler, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 2006.

Notes

(1) Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., with Charles Brock, “Whistler and America” in Richard Dormant and Margaret F. McDonald, James McNeill Whistler, exh. cat. (London: Tate Gallery; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994), pp. 29–38.

(2) See Eric Denker, In Pursuit of the Butterfly: Portraits of James McNeill Whistler, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery/University of Washington Press, 1995).

(3) Charles Baudelaire, “Painters and Etchers,” Le Boulevard (Paris), September 14, 1862, as quoted in Robin Spencer, ed., Whistler: A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1989), p. 60.

(4) Tedeschi, Martha, Nesta Spink, Harriet Stratis, with Britt Salvesen and Katherine Lochnan, A Catalogue Raisonne. Volume I of the Lithographs of James McNeill Whistler, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago/Arie and Ida Crown Memorial, 1998), pp. 58–62.

(5) John Ruskin, “Letter 79: Life Guards of New Life,” Fors Clavigera 7 (July 1877), as collected in E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds., The Works of John Ruskin (London: George Allen, 1903–12), vol. 29, p. 160.

(6) Anonymous author, “A Chat with Mr. Whistler,” Pall Mall Budget, March 13, 1890, as reproduced in Spencer, Whistler, pp. 269–70.

American

(Lowell, Massachusetts, 1834 - 1903, London, England)

James McNeill Whistler was a painter, printmaker, and theoretician whose work is recognized today as an important achievement in nineteenth-century art. Aesthetically, however, Whistler always pursued his own single-minded vision of art rather than adopting one of the mainstream approaches then in vogue. Although the gregarious painter both craved and received enormous attention in England, France, and the United States during his lifetime, his unique development and achievement has placed him outside the accepted narrative of the history of art.

Americans claim Whistler because he was born in Massachusetts to American parents, and because he always retained his identification as an American, as an outsider living in a hostile British artistic environment. (1) Yet, equally, he might be claimed by France, where he formed his aesthetic opinions in the cauldron of French theory at midcentury and where his most significant training occurred. Or yet again, he might be (and often is) included in a survey of nineteenth-century art in Britain, where he lived for the overwhelming majority of his adult life. It is prudent to recall that Whistler spent only fifteen of his first twenty-one years in the United States, never returning to this side of the Atlantic after attaining his majority.

Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts on July 11, 1834, a fact he regularly attempted to obscure for much of the rest of his life. (2) George Washington Whistler, the artist’s father, was a civil engineer in the United States Army. In 1842, Major Whistler accepted the invitation of Nicholas I, czar of Russia, to design and build the first railway line from Moscow to St. Petersburg. The family followed the Major to Russia a year later, and the young James spent much of the next six years in St. Petersburg, taking his first art lessons at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. His hosts at the Russian court, a cultivated and cosmopolitan circle in which French was spoken, regarded James as the child of an honored visitor. He appears to have been shaped in some ways by his experience during these formative years—he received a broad education, became familiar with art, and although often the center of attention, became accustomed to thinking of himself as an outsider. He also had the opportunity to spend time in London with his brother-in-law Francis Seymour Haden, a doctor, an amateur etcher, and an astute collector.

The death of Major Whistler in April 1849 necessitated the family’s relocation to Pomfret, Connecticut. Two years later, the young artist followed in his father’s footsteps and entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, then under Colonel Robert E. Lee. Whistler excelled at drawing in classes taught by Robert W. Weir but exhibited a notable lack of discipline in his other coursework, which led to his dismissal from the academy in June 1854. After a short apprenticeship at Thomas Winan’s locomotive works in Baltimore, he arrived in Washington in November with an appointment to the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. He lasted there for less than two months, making it just into the New Year before being summarily dismissed for bad work habits and lack of attendance. Though his period at the Geodetic Survey was brief, it proved crucial to his later development, since this is where he experienced his first serious exposure to etching learned to etch. In July 1855, Whistler turned twenty-one, at which point he began receiving an income from his father’s estate, and soon thereafter moved to Paris to study art, leaving the United States never to return.

The problem of categorization that plagues Whistler as a painter is not considered as serious a detriment in appreciating his career as a printmaker. Influential writer Charles-Pierre Baudelaire commended Whistler’s talent in that realm in 1862. “Just the other day a young American artist, M. Whistler, was showing at the Galerie Martinet a set of etchings, as subtle and lively as improvisation and inspiration, representing the banks of the Thames, wonderful tangles of rigging, yardarms and rope; farragos of fog, furnaces and corkscrews of smoke; the profound and intricate poetry of a vast capital.” (3) Four years prior, in spring 1859, Whistler’s prints had won acceptance at the Salon in Paris and at the Royal Academy in London. In the 1860s, even when Whistler’s paintings met with mixed reception, and regular rejection from both the Academy and the Salon, critics simultaneously acknowledged his strengths as a draughtsman and a consummate etcher.

From the outset of his career, Whistler conceived of much of his graphic work in terms of sets, to be presented and marketed as groups of related images, inspired by both the vogue for Japanese woodblock prints, and the recognized master of the revival of etching, Charles Meryon. His earliest important prints were included in “Twelve Etchings from Nature” of 1858, generally referred to as the “French Set”. He was planning a second set at the time of his immigration to England, although his “Sixteen Etchings of Scenes of the Thames,” referred to as the Thames Set, was not issued until 1871. Later, he went to Venice in September 1879 with the explicit commission to render a set of twelve etchings of the city in a brief three month period. That three-month period stretched to fourteen, during which he executed a sufficient number to publish both the original dozen, the “First Venice Set”, and a second series of mostly Venetian scenes, the “Second Venice Set”. A decade later, in 1889, he traveled to Amsterdam, the city of his artistic idol Rembrandt van Rijn, where he planned and executed the Amsterdam Set.

Whistler moved to Chelsea in 1863 and lived there, with rare breaks in Paris and Venice, for the rest of his life. Though many of the paintings of the 1860s reflect these new surroundings, the artist largely abandoned etching during the second half of the 1860s. Whistler worked episodically on etching and drypoint through the 1870s, preoccupied as he was with painting. The lithographs Whistler executed in 1878 are far more atmospheric than anything he had yet attempted in etching and drypoint. This had to do with the expressive vocabulary inherent in the lithographic process, one that allowed the artist to conceive and work the design in tone rather than line. Thomas Way, the printer who taught Whistler lithography, arranged for Whistler to draw and paint on a stone while floating on a barge on the Thames in the dock area of East London where Whistler had first etched twenty years before. (4) His final two great print series were created over a fourteen month period in Venice.

The story of Whistler in Venice is the centerpiece to the Whistler legend, a tale of fall from grace, exile, and triumphant return. Whistler made a calculated decision to bring suit against the critic John Ruskin for libel, resulting in perhaps the most celebrated trial in the history of art, Whistler v. Ruskin. Ruskin had condemned Whistler’s work in a review that appeared in the July 1877 issue of his Fors Clavigera. “I have seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” he wrote. (5) Although the jury found in favor of Whistler, agreeing that Ruskin had committed libel, they awarded him only one farthing (a quarter of a penny), rather than the £1,000 that he had sought in the action. Interpreting the jury’s award as a strong reproach to Whistler for having brought the matter to trial, the judge directed that the two sides each absorb their own expenses. The decision led to Whistler’s bankruptcy in May 1879. By the summer financial insolvency and a lack of new patronage resulting from adverse publicity left Whistler reeling; he accepted a commission from a commercial gallery in London, the Fine Art Society, to etch a series of prints of Venice for December holiday sales.

He wrestled with the subject matter of Venice, overwhelmed by the remarkable visual riches of the city. He wanted to develop his own approach to the city, one that would distinguish his work from the anecdotal sentimentality of established Victorian imagery. His achievement relied in part on this original conception of a Venice that was best known to contemporary Venetians—the long vistas, the back alleys, the quiet canals and idiosyncratic bridges that cross them, and the isolated squares of the everyday life of the city. The artist rendered few images of the usual sights, the Piazza San Marco, the Basilica, and the Grand Canal. The artist subsequently remained in Venice for fourteen months, during which he executed more than fifty prints, a handful of paintings, and approximately one hundred pastels. The etchings are at the core of Whistler’s Venetian achievement. Upon his return to England, the exhibitions of his Venetian etchings and pastels reestablished his artistic reputation, and provided a turning point in his career.

On August 11, 1888, Whistler married Beatrice Godwin, the affluent widow of his friend and collaborator, architect E. W. Godwin. In September of the following year, Whistler and Trixie spent two months in Amsterdam where the artist drew ten plates that he hoped to publish as a set through the Fine Art Society. However, since he had never completed the editions of the First Venice Set of 1880, the firm declined his offer.

In an article of March 11, 1890, in the Pall Mall Budget, he is recorded as having first displayed and discussed the individual Amsterdam etchings, and then to have summed up his etching career in this way:

“I divide myself into three periods,” he says, being in his most serious and sensible mood. “First you see me at work on the Thames,” producing one of the famous series. “Now, there you have the crude and hard detail of the beginner. So far, so good. There, you see, all is sacrificed to exactitude of outline. Presently, and almost unconsciously, I begin to criticize myself, and to feel the craving of the artist for form and colour. The result was the second stage, which my enemies call The Inchoate, and I call Impressionism. The third stage I have shown you. In that I have endeavoured to combine stages one and two. You have the elaboration of the first stage and the quality of the second.” (6)

Whistler died on July 17, 1903 in London.

Text based upon Eric Denker, “Whistler and the Search for Printed Tone,” Fleeting Impressions: Prints by James McNeill Whistler, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 2006.

Notes

(1) Nicolai Cikovsky, Jr., with Charles Brock, “Whistler and America” in Richard Dormant and Margaret F. McDonald, James McNeill Whistler, exh. cat. (London: Tate Gallery; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994), pp. 29–38.

(2) See Eric Denker, In Pursuit of the Butterfly: Portraits of James McNeill Whistler, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Portrait Gallery/University of Washington Press, 1995).

(3) Charles Baudelaire, “Painters and Etchers,” Le Boulevard (Paris), September 14, 1862, as quoted in Robin Spencer, ed., Whistler: A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1989), p. 60.

(4) Tedeschi, Martha, Nesta Spink, Harriet Stratis, with Britt Salvesen and Katherine Lochnan, A Catalogue Raisonne. Volume I of the Lithographs of James McNeill Whistler, (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago/Arie and Ida Crown Memorial, 1998), pp. 58–62.

(5) John Ruskin, “Letter 79: Life Guards of New Life,” Fors Clavigera 7 (July 1877), as collected in E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, eds., The Works of John Ruskin (London: George Allen, 1903–12), vol. 29, p. 160.

(6) Anonymous author, “A Chat with Mr. Whistler,” Pall Mall Budget, March 13, 1890, as reproduced in Spencer, Whistler, pp. 269–70.

Artist Objects