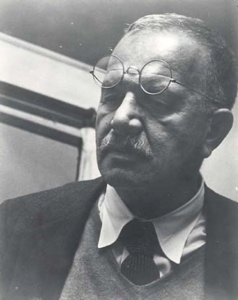

Ben Shahn

American, born Lithuania

(Kovno, Lithuania, 1898 – 1969, New York, New York)

The artist, Ben Shahn, was born on September 12, 1898 in Kovno, Lithuania. (1) Both his parents came from a long line of craftspeople; his father's family were woodcarvers, and his mother's family were potters. Shahn was educated at a Hebrew school where he studied the Bible and the Jewish religion, its history, rites, and symbols. In addition to Hebrew, he learned to speak Yiddish and Russian. He also began to draw quite early in life. (2)

When Shahn was five, his Socialist father was sentenced to Siberia for his political beliefs but managed to escape to Sweden and eventually to South Africa and the United States. Three years later, in 1906, the rest of the Shahn family immigrated to America, settling in Brooklyn. At the age of fourteen, Shahn was taken out of school and apprenticed to a Manhattan lithographer (Hessenberg's) where he worked for the next four years. He continued his schooling by taking night courses at the Educational Alliance. Also during this period, an aunt introduced him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where he fell in love with Italian fourteenth and fifteenth century painting, particularly the works of Giotto. In 1916, he enrolled in a life-drawing class at the Art Students' League.

In 1917, Shahn completed his apprenticeship and left Hessenberg's shop, though he continued to do free-lance lithography work. In 1919, he enrolled at New York University as a biology student. Though he was a successful student and won several summer scholarships to the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, Shahn eventually decided to reconsider a career as an artist. He transferred to the City College of New York in 1921 and enrolled at the National Academy of Design the following year. He also resumed studies at the Art Students' League where he was enrolled from 1925 to 1927.

In 1925, Shahn and his new wife, Tillie (Mathilda Goldstein), traveled to Europe and North Africa, eventually settling in Paris where Shahn studied French at the Sorbonne and art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. They returned to Paris and North Africa again in 1927. Shahn produced a number of watercolors and oil paintings of this trip and these works were exhibited at the Downtown Gallery in Shahn's first one-man show when the Shahns returned to New York. In 1929, Shahn met Walker Evans while summering in Massachusetts. They eventually shared a studio and Evans introduced Shahn to the art of photography.

Two events which were to have a lasting impact on the course of Shahn's career occurred in the early 1930s. The first was his decision in 1931 to produce a series of gouache paintings on the trial of two immigrant workmen, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who were accused of murdering a paymaster and were eventually executed. The previous year, Shahn had executed another series of watercolors on the Dreyfus affair, a case in which a late nineteenth-century Jewish officer in the French army was falsely accused of treason and exiled. The popular success of both these series encouraged Shahn to continue using art as a form of social commentary, a course he pursued throughout the remainder of his career. He followed the Sacco and Vanzetti project with a series on the bombing trial of labor leader, Tom Mooney, in 1932.

The second pivotal event in Shahn's career was his introduction to mural painting in 1933. Shahn was asked to assist Diego Rivera on a mural project for the RCA building at Rockefeller Center. Though the project was eventually canceled because it included a controversial portrait of Lenin, Shahn continued to work with Rivera on a series of fresco panels for the New Workers' School. Shahn also began executing his own series of eight tempera studies for a mural on Prohibition for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). The design was eventually rejected by the Municipal Art Commission and never executed.

In 1935, Shahn was asked to join the Resettlement Administration, Special Skills staff in Washington, D. C. and was then loaned to the photographic unit of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) under Roy Stryker to help document rural poverty in America. Shahn traveled through the South and Midwest with his new wife, Bernarda Bryson, documenting American small-town culture with a 35 mm Leica camera. It was Shahn's first exposure to the United States outside of New York and he was impressed by the variety of people and the changing landscape that he encountered. Shahn was particularly attracted to the hand-lettered signs he saw on stores, gas stations, and restaurants throughout rural America. By the end of the project, Shahn had produced over 6,000 photographs for the FSA.

In 1939, after leaving the FSA, Shahn painted his first mural for the Jersey Homesteads housing development. Shahn and his wife were then commissioned to decorate the Bronx Central Annex Post Office with thirteen large fresco panels. In 1940, Shahn began working on a mural for the Social Security Building (now Health, Education, and Welfare) in Washington. In 1941, his work was included in La Pintura Contemporanea Norteamericana , a circulating exhibition of American art that toured Latin American countries. He also spent part of that same year studying fresco technique and learning silkscreen printing at the Art Students' League.

In 1942, Shahn began working for the Office of War Information designing posters and pamphlets. A year later he left the agency and began to do commercial work, as well as design posters for the CIO's Political Action Committee. He later became director of their graphic arts division. In 1947, the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective of Shahn's work which later traveled to eight other American cities. Also that year, James Soby published the first of a series of monographs on Shahn's work. (3) In 1948, Shahn was named one of the ten leading American painters in a Look magazine poll of museum directors.

In 1951, Shahn began teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, replacing Max Beckmann who had just died. This was Shahn's first full-time teaching assignment, though he had taught summer school at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the University of Colorado. During this period, Shahn began to experiment extensively with fine art printmaking, trying his hand at lithography and serigraphy and often adding color by hand. A number of stylistic changes also are visible in his work from this period, particularly an increase in symbolism and a new interest in religious content and symbols. (4)

The latter decades of the 1950s were years of distinction for Shahn. In 1955, the Downtown Gallery held a retrospective of his work to celebrate their 25 year relationship with him. Also that year, Shahn had his first one-man show in Italy at the Galleria Tartaruga in Rome and collaborated with Edward R. Murrow of CBS on a program about Louis Armstrong. In 1956, Shahn was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and then was asked to be the Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard. In 1957, Shahn was asked to design and oversee installation of his first mosaic mural at the William E. Grady Vocational High School in Brooklyn, and James Soby published his monograph on Shahn's graphic work. (5) In 1958, Shahn was awarded the gold medal of the American Institute of Graphic Arts. He began to experiment with new forums for his work, designing sets and posters for Jerome Robbins' ballet "New York Export—Opus Jazz" and making masks for a play by Archibald MacLeish. In 1959, he was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Throughout this period, Shahn also designed and executed a number of murals for Jewish temples across the United States.

Early in 1960, Shahn traveled to Asia where he learned calligraphy as well as some Chinese letters and ideograms. In 1961, a retrospective exhibition of his work was prepared by the circulating exhibitions department of the Museum of Modern Art and traveled to Amsterdam, Brussels, Rome, and Vienna. That same year, Shahn was awarded the Contemporary American Oil Paintings Exhibition Medal by the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. In 1962, Shahn was commissioned to paint a portrait of Dag Hammarskjold, then Secretary General of the United Nations, and was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from Princeton. In 1963, James Soby's third monograph on Shahn was published, (6) and in 1964 Shahn was awarded the National Institute of Arts and Letters Gold Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Additional honorary degrees were conferred in the following years including a Doctorate of Humane Letters from Hebrew Union College, a Doctor of Letters degree from Rutgers, and Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from the Pratt Institute and Harvard University.

In 1968, Shahn's health began to fail and the shock of his daughter, Susanna's sudden death further weakened him. He continued to work, however, completing his portfolio of lithographs, For the Sake of a Single Verse, and designing a monument in his daughter's honor. He died March 14, 1969. In his memory, a retrospective was held at the New Jersey State Museum and a traveling exhibit was organized and circulated throughout Japan.

Shahn's works can be found in the public collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Chicago Art Institute, Harvard University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Art in Stockholm, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the San Francisco Musem of Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Vatican Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, among many others. (7) During his career, Shahn also produced a great variety of commercial art for such corporations as CBS, Capitol Records, the Container Corporation of America, Columbia Records, The Singer Company, Random House, Little Brown, and Harvard University Press. From 1933 on, he actively exhibited his works at shows throughout the world, many of them one-man exhibitions or retrospectives. (8) Shahn also published a number of books about his art, aesthetics, and the art world in general including Paragraphs on Art (1952),The Biography of a Painting (1956), The Shape of Content (1957), Alphabet of Creation (1963), and Love and Joy About Letters (1963). (9)

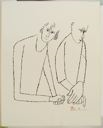

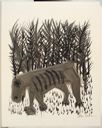

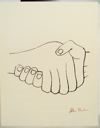

Shahn worked in a variety of media including drawing, painting, printmaking, mural painting, tapestry making, mosaic, stained glass, photography, and book illustration. He preferred to draw with a small, narrow brush rather than a pen or pencil, and he chose tempera over oil paint because he disliked the layering characteristic of oil painting. While working with Diego Rivera, Shahn adopted Rivera's method of underpainting in black, but he eventually changed to sienna and ochre, and eventually began to use variegated colors. (10) Shahn did not produce full studies for his compositions, but kept shorthand notes and small images as records of his ideas. (11) Many of Shahn's works are signed with his personal "chop" composed from the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

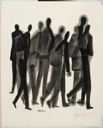

Shahn's early paintings of the 1920s are strongly reminiscent of the Post Impressionist artists he was studying, particularly Cezanne. (12) But by the 1930s, Shahn's works display many of the features of his mature style with its emphasis on line, frontal almost iconic presentation of its subjects, and pared down compositions. Shahn's works from the 1940s and after are increasingly allegorical and symbolic in subject. Lettering also becomes an integral part of his compositions during this period. By the 1950s, Shahn's works reveal a new interest in religious content and in the 1960s, mural painting and photography once again become important components of his oeuvre.

Because of his early and extensive training in lithography, Shahn's works are structured and described by line. (13) From lithography, Shahn also retained a lifelong fascination with letters and lettering styles and experimented with them regularly in his work. Communication and storytelling also are central elements of Shahn's works. Devices such as distortions of scale and perspective, the use of dramatic gesture, and the use of symbols, signs, and text all are used to help convey his intentions. (14)

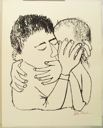

Shahn's compositions tend to be uncluttered and focused on human actions, interactions, or emotions. Details are usually carefully noted. Though Shahn's murals often seem more crowded than his other works, internally they are divided into scenes or vignettes which, like his easel paintings and prints, are individually rather spare. Shahn tends to collapse space and skew perspective in many of his works, creating landscapes and buildings which look like shallow, flattened stage sets thus focusing attention on the figures placed in front of them. As well, these generalized settings remove Shahn's themes from a particular time or place and make them universally applicable.

Shahn felt that the function of art was to broaden the human spirit (15) and he was deeply interested in the joys and evils of human society, and the functioning of individuals within it. (16) Shahn once said: "The whole audience of art is an audience of individuals. Each of them comes to the painting or sculpture because there he can be told that he, the individual, transcends all classes and flouts all predictions. In the work of art he finds his uniqueness affirmed." (17) Though Shahn experimented with the techniques of abstract art to enrich his work, people were almost always the focus of his interest.(18) He explored a mixture of human emotions ranging between the extremes of caricature and tragedy, (19) and illustrated themes from the hopeless to the spiritual.

(1) The bibliography on Ben Shahn is extensive and of generally high quality. Only a handful of the variety of references available on Shahn's life and career were consulted for this essay. They include: Frank Getlein, Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, New York, 1968; Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1969; Kenneth Prescott, Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1971; John D. Morse, editor, Ben Shahn, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972; Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Ben Shahn, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1972; Kenneth W. Prescott, The Complete Graphic Works of Ben Shahn, Quadrangle/New York Times Book Company, New York, 1973; The Drawings of Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1976; Richard Whelan, Art in America 64, May 1976, p. 35; Virginia Mecklenburg, The Public as Patron: A History of the Treasury Department Mural Program Illustrated with Paintings from the Collection of the University of Maryland Art Gallery, University of Maryland, Department of Art, 1979; Greta Berman and Jeffrey Wechsler, Realism and Realities: The Other Side of American Painting 1940-1960, Rutgers University Art Gallery, 1981; Kenneth W. Prescott, Prints and Posters of Ben Shahn, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1982; Graham Hughes, Arts Review Volume 37 no. 12, June 22, 1984, London, p. 310; Harriet W. Fowler, New Deal Art: WPA Works at the University of Kentucky, University of Kentucky Art Museum, 1985. Also recommended are: Kenneth W. Prescott, Ben Shahn: A Retrospective 1898-1969, The Jewish Museum, New York, 1976 and the 1947, 1957, and 1963 monographs on Ben Shahn by James Thrall Soby. Full bibliographic references for these monographs are given in notes 3, 5, 6 below.

(2) "Well, the first thing that I can remember I drew, and it was natural that as soon as I could have access to coloring material, I colored whether it was crayon or watercolor. Now when I was a youngster of about twelve, I looked upon oil as the very highest thing, and begged for oil paints. But with experience, I revalued all those things. But I did think of myself as an artist, awfully young." (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 42).

(3) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn, The Museum of Modern Art and Penguin Books, New York, 1947.

(4) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 183.

(5) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn. His Graphic Art, George Braziller, New York, 1957.

(6) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn Paintings, George Braziller, New York, 1963.

(7) A definitive collection of Shahn's graphic work is housed in the New Jersey State Museum. A computerized archive of articles, books, and other information on Ben Shahn's career has been established by Dr. Stephen Lee Taller, 743 Spruce Street, Berkeley, California, 94707.

(8) Retrospectives of Shahn's work have been organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain (1947), the Museum of Modern Art (1948), the Downtown Gallery, New York (1955), the Fogg Art Museum (1956), the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art (1961-1962), the New Jersey State Museum (1969), the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (1970), Kennedy Galleries, New York (1973), the New Jersey State Museum (1976), and Isetan Bijutsukan, Tokyo (1991).

(9) Excerpts of all these texts, the full text of Love and Joy About Letters, and excerpts from interviews and lectures by Ben Shahn are reproduced in Ben Shahn, John D. Morse, editor, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972.

(10) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 133.

(11) Well, I am actually more inclined to [start] with images. And I keep notes. And the notes are made half in little images and half in single words. A kind of shorthand of image words, if you wish. But I certainly do not have a complete image because if I had a complete image I think I would lose my interest in it. The area of discovery, the area of exploration that exists in painting is to me the most intriguing and the most rewarding one." (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 43).

(12) Prescott, 1982, p. v

(13) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 308

(14) "Ben was a storyteller, and his art must necessarily reflect storytelling. He loved the great biblical figures and the mythological ones and had invented his own menagerie of mythical beasts and creatures. Story was for him a source of multitudinous images, an inexhaustible museum of shapes, objects, and personages." (Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 74; see also Getlein, 1968 and Prescott, 1982).

(15) "It is my belief that the work of art is a product of the human spirit and that, conversely, the function of the work of art is to broaden and enrich the human spirit" (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 203).

(16)"His concerns moved him easily into the realm of activism, and he was eager to have his art feed directly into the tributaries that alter and quicken society's meandering flow. When he focused on the ills of society, it was not in bitterness but in the hope of eradicating these obstacles to the fulfillment of the American dream." (Prescott, 1982, p. v).

(17) Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 79.

(18) "Ben Shahn's art stood somewhere between the abstract and what is called figurative, borrowing from the one its material riches of color, shape, and texture, its explorations in form, its preference for inner organization as against outer verisimilitude, from the other its focus upon man as the center of value and as the most interesting object on earth." (Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 15)

(19) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 76.

Margaret Bullock/December, 1996

American, born Lithuania

(Kovno, Lithuania, 1898 – 1969, New York, New York)

The artist, Ben Shahn, was born on September 12, 1898 in Kovno, Lithuania. (1) Both his parents came from a long line of craftspeople; his father's family were woodcarvers, and his mother's family were potters. Shahn was educated at a Hebrew school where he studied the Bible and the Jewish religion, its history, rites, and symbols. In addition to Hebrew, he learned to speak Yiddish and Russian. He also began to draw quite early in life. (2)

When Shahn was five, his Socialist father was sentenced to Siberia for his political beliefs but managed to escape to Sweden and eventually to South Africa and the United States. Three years later, in 1906, the rest of the Shahn family immigrated to America, settling in Brooklyn. At the age of fourteen, Shahn was taken out of school and apprenticed to a Manhattan lithographer (Hessenberg's) where he worked for the next four years. He continued his schooling by taking night courses at the Educational Alliance. Also during this period, an aunt introduced him to the Metropolitan Museum of Art where he fell in love with Italian fourteenth and fifteenth century painting, particularly the works of Giotto. In 1916, he enrolled in a life-drawing class at the Art Students' League.

In 1917, Shahn completed his apprenticeship and left Hessenberg's shop, though he continued to do free-lance lithography work. In 1919, he enrolled at New York University as a biology student. Though he was a successful student and won several summer scholarships to the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Massachusetts, Shahn eventually decided to reconsider a career as an artist. He transferred to the City College of New York in 1921 and enrolled at the National Academy of Design the following year. He also resumed studies at the Art Students' League where he was enrolled from 1925 to 1927.

In 1925, Shahn and his new wife, Tillie (Mathilda Goldstein), traveled to Europe and North Africa, eventually settling in Paris where Shahn studied French at the Sorbonne and art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. They returned to Paris and North Africa again in 1927. Shahn produced a number of watercolors and oil paintings of this trip and these works were exhibited at the Downtown Gallery in Shahn's first one-man show when the Shahns returned to New York. In 1929, Shahn met Walker Evans while summering in Massachusetts. They eventually shared a studio and Evans introduced Shahn to the art of photography.

Two events which were to have a lasting impact on the course of Shahn's career occurred in the early 1930s. The first was his decision in 1931 to produce a series of gouache paintings on the trial of two immigrant workmen, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who were accused of murdering a paymaster and were eventually executed. The previous year, Shahn had executed another series of watercolors on the Dreyfus affair, a case in which a late nineteenth-century Jewish officer in the French army was falsely accused of treason and exiled. The popular success of both these series encouraged Shahn to continue using art as a form of social commentary, a course he pursued throughout the remainder of his career. He followed the Sacco and Vanzetti project with a series on the bombing trial of labor leader, Tom Mooney, in 1932.

The second pivotal event in Shahn's career was his introduction to mural painting in 1933. Shahn was asked to assist Diego Rivera on a mural project for the RCA building at Rockefeller Center. Though the project was eventually canceled because it included a controversial portrait of Lenin, Shahn continued to work with Rivera on a series of fresco panels for the New Workers' School. Shahn also began executing his own series of eight tempera studies for a mural on Prohibition for the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP). The design was eventually rejected by the Municipal Art Commission and never executed.

In 1935, Shahn was asked to join the Resettlement Administration, Special Skills staff in Washington, D. C. and was then loaned to the photographic unit of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) under Roy Stryker to help document rural poverty in America. Shahn traveled through the South and Midwest with his new wife, Bernarda Bryson, documenting American small-town culture with a 35 mm Leica camera. It was Shahn's first exposure to the United States outside of New York and he was impressed by the variety of people and the changing landscape that he encountered. Shahn was particularly attracted to the hand-lettered signs he saw on stores, gas stations, and restaurants throughout rural America. By the end of the project, Shahn had produced over 6,000 photographs for the FSA.

In 1939, after leaving the FSA, Shahn painted his first mural for the Jersey Homesteads housing development. Shahn and his wife were then commissioned to decorate the Bronx Central Annex Post Office with thirteen large fresco panels. In 1940, Shahn began working on a mural for the Social Security Building (now Health, Education, and Welfare) in Washington. In 1941, his work was included in La Pintura Contemporanea Norteamericana , a circulating exhibition of American art that toured Latin American countries. He also spent part of that same year studying fresco technique and learning silkscreen printing at the Art Students' League.

In 1942, Shahn began working for the Office of War Information designing posters and pamphlets. A year later he left the agency and began to do commercial work, as well as design posters for the CIO's Political Action Committee. He later became director of their graphic arts division. In 1947, the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective of Shahn's work which later traveled to eight other American cities. Also that year, James Soby published the first of a series of monographs on Shahn's work. (3) In 1948, Shahn was named one of the ten leading American painters in a Look magazine poll of museum directors.

In 1951, Shahn began teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, replacing Max Beckmann who had just died. This was Shahn's first full-time teaching assignment, though he had taught summer school at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the University of Colorado. During this period, Shahn began to experiment extensively with fine art printmaking, trying his hand at lithography and serigraphy and often adding color by hand. A number of stylistic changes also are visible in his work from this period, particularly an increase in symbolism and a new interest in religious content and symbols. (4)

The latter decades of the 1950s were years of distinction for Shahn. In 1955, the Downtown Gallery held a retrospective of his work to celebrate their 25 year relationship with him. Also that year, Shahn had his first one-man show in Italy at the Galleria Tartaruga in Rome and collaborated with Edward R. Murrow of CBS on a program about Louis Armstrong. In 1956, Shahn was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and then was asked to be the Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard. In 1957, Shahn was asked to design and oversee installation of his first mosaic mural at the William E. Grady Vocational High School in Brooklyn, and James Soby published his monograph on Shahn's graphic work. (5) In 1958, Shahn was awarded the gold medal of the American Institute of Graphic Arts. He began to experiment with new forums for his work, designing sets and posters for Jerome Robbins' ballet "New York Export—Opus Jazz" and making masks for a play by Archibald MacLeish. In 1959, he was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Throughout this period, Shahn also designed and executed a number of murals for Jewish temples across the United States.

Early in 1960, Shahn traveled to Asia where he learned calligraphy as well as some Chinese letters and ideograms. In 1961, a retrospective exhibition of his work was prepared by the circulating exhibitions department of the Museum of Modern Art and traveled to Amsterdam, Brussels, Rome, and Vienna. That same year, Shahn was awarded the Contemporary American Oil Paintings Exhibition Medal by the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. In 1962, Shahn was commissioned to paint a portrait of Dag Hammarskjold, then Secretary General of the United Nations, and was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from Princeton. In 1963, James Soby's third monograph on Shahn was published, (6) and in 1964 Shahn was awarded the National Institute of Arts and Letters Gold Medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Additional honorary degrees were conferred in the following years including a Doctorate of Humane Letters from Hebrew Union College, a Doctor of Letters degree from Rutgers, and Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from the Pratt Institute and Harvard University.

In 1968, Shahn's health began to fail and the shock of his daughter, Susanna's sudden death further weakened him. He continued to work, however, completing his portfolio of lithographs, For the Sake of a Single Verse, and designing a monument in his daughter's honor. He died March 14, 1969. In his memory, a retrospective was held at the New Jersey State Museum and a traveling exhibit was organized and circulated throughout Japan.

Shahn's works can be found in the public collections of the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Chicago Art Institute, Harvard University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Museum of Art in Stockholm, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the San Francisco Musem of Art, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Vatican Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome, among many others. (7) During his career, Shahn also produced a great variety of commercial art for such corporations as CBS, Capitol Records, the Container Corporation of America, Columbia Records, The Singer Company, Random House, Little Brown, and Harvard University Press. From 1933 on, he actively exhibited his works at shows throughout the world, many of them one-man exhibitions or retrospectives. (8) Shahn also published a number of books about his art, aesthetics, and the art world in general including Paragraphs on Art (1952),The Biography of a Painting (1956), The Shape of Content (1957), Alphabet of Creation (1963), and Love and Joy About Letters (1963). (9)

Shahn worked in a variety of media including drawing, painting, printmaking, mural painting, tapestry making, mosaic, stained glass, photography, and book illustration. He preferred to draw with a small, narrow brush rather than a pen or pencil, and he chose tempera over oil paint because he disliked the layering characteristic of oil painting. While working with Diego Rivera, Shahn adopted Rivera's method of underpainting in black, but he eventually changed to sienna and ochre, and eventually began to use variegated colors. (10) Shahn did not produce full studies for his compositions, but kept shorthand notes and small images as records of his ideas. (11) Many of Shahn's works are signed with his personal "chop" composed from the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

Shahn's early paintings of the 1920s are strongly reminiscent of the Post Impressionist artists he was studying, particularly Cezanne. (12) But by the 1930s, Shahn's works display many of the features of his mature style with its emphasis on line, frontal almost iconic presentation of its subjects, and pared down compositions. Shahn's works from the 1940s and after are increasingly allegorical and symbolic in subject. Lettering also becomes an integral part of his compositions during this period. By the 1950s, Shahn's works reveal a new interest in religious content and in the 1960s, mural painting and photography once again become important components of his oeuvre.

Because of his early and extensive training in lithography, Shahn's works are structured and described by line. (13) From lithography, Shahn also retained a lifelong fascination with letters and lettering styles and experimented with them regularly in his work. Communication and storytelling also are central elements of Shahn's works. Devices such as distortions of scale and perspective, the use of dramatic gesture, and the use of symbols, signs, and text all are used to help convey his intentions. (14)

Shahn's compositions tend to be uncluttered and focused on human actions, interactions, or emotions. Details are usually carefully noted. Though Shahn's murals often seem more crowded than his other works, internally they are divided into scenes or vignettes which, like his easel paintings and prints, are individually rather spare. Shahn tends to collapse space and skew perspective in many of his works, creating landscapes and buildings which look like shallow, flattened stage sets thus focusing attention on the figures placed in front of them. As well, these generalized settings remove Shahn's themes from a particular time or place and make them universally applicable.

Shahn felt that the function of art was to broaden the human spirit (15) and he was deeply interested in the joys and evils of human society, and the functioning of individuals within it. (16) Shahn once said: "The whole audience of art is an audience of individuals. Each of them comes to the painting or sculpture because there he can be told that he, the individual, transcends all classes and flouts all predictions. In the work of art he finds his uniqueness affirmed." (17) Though Shahn experimented with the techniques of abstract art to enrich his work, people were almost always the focus of his interest.(18) He explored a mixture of human emotions ranging between the extremes of caricature and tragedy, (19) and illustrated themes from the hopeless to the spiritual.

(1) The bibliography on Ben Shahn is extensive and of generally high quality. Only a handful of the variety of references available on Shahn's life and career were consulted for this essay. They include: Frank Getlein, Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, New York, 1968; Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1969; Kenneth Prescott, Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1971; John D. Morse, editor, Ben Shahn, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972; Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Ben Shahn, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, 1972; Kenneth W. Prescott, The Complete Graphic Works of Ben Shahn, Quadrangle/New York Times Book Company, New York, 1973; The Drawings of Ben Shahn, Kennedy Galleries, Inc., New York, 1976; Richard Whelan, Art in America 64, May 1976, p. 35; Virginia Mecklenburg, The Public as Patron: A History of the Treasury Department Mural Program Illustrated with Paintings from the Collection of the University of Maryland Art Gallery, University of Maryland, Department of Art, 1979; Greta Berman and Jeffrey Wechsler, Realism and Realities: The Other Side of American Painting 1940-1960, Rutgers University Art Gallery, 1981; Kenneth W. Prescott, Prints and Posters of Ben Shahn, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1982; Graham Hughes, Arts Review Volume 37 no. 12, June 22, 1984, London, p. 310; Harriet W. Fowler, New Deal Art: WPA Works at the University of Kentucky, University of Kentucky Art Museum, 1985. Also recommended are: Kenneth W. Prescott, Ben Shahn: A Retrospective 1898-1969, The Jewish Museum, New York, 1976 and the 1947, 1957, and 1963 monographs on Ben Shahn by James Thrall Soby. Full bibliographic references for these monographs are given in notes 3, 5, 6 below.

(2) "Well, the first thing that I can remember I drew, and it was natural that as soon as I could have access to coloring material, I colored whether it was crayon or watercolor. Now when I was a youngster of about twelve, I looked upon oil as the very highest thing, and begged for oil paints. But with experience, I revalued all those things. But I did think of myself as an artist, awfully young." (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 42).

(3) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn, The Museum of Modern Art and Penguin Books, New York, 1947.

(4) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 183.

(5) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn. His Graphic Art, George Braziller, New York, 1957.

(6) James Thrall Soby, Ben Shahn Paintings, George Braziller, New York, 1963.

(7) A definitive collection of Shahn's graphic work is housed in the New Jersey State Museum. A computerized archive of articles, books, and other information on Ben Shahn's career has been established by Dr. Stephen Lee Taller, 743 Spruce Street, Berkeley, California, 94707.

(8) Retrospectives of Shahn's work have been organized by the Arts Council of Great Britain (1947), the Museum of Modern Art (1948), the Downtown Gallery, New York (1955), the Fogg Art Museum (1956), the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art (1961-1962), the New Jersey State Museum (1969), the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (1970), Kennedy Galleries, New York (1973), the New Jersey State Museum (1976), and Isetan Bijutsukan, Tokyo (1991).

(9) Excerpts of all these texts, the full text of Love and Joy About Letters, and excerpts from interviews and lectures by Ben Shahn are reproduced in Ben Shahn, John D. Morse, editor, Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972.

(10) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 133.

(11) Well, I am actually more inclined to [start] with images. And I keep notes. And the notes are made half in little images and half in single words. A kind of shorthand of image words, if you wish. But I certainly do not have a complete image because if I had a complete image I think I would lose my interest in it. The area of discovery, the area of exploration that exists in painting is to me the most intriguing and the most rewarding one." (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 43).

(12) Prescott, 1982, p. v

(13) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 308

(14) "Ben was a storyteller, and his art must necessarily reflect storytelling. He loved the great biblical figures and the mythological ones and had invented his own menagerie of mythical beasts and creatures. Story was for him a source of multitudinous images, an inexhaustible museum of shapes, objects, and personages." (Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 74; see also Getlein, 1968 and Prescott, 1982).

(15) "It is my belief that the work of art is a product of the human spirit and that, conversely, the function of the work of art is to broaden and enrich the human spirit" (Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 203).

(16)"His concerns moved him easily into the realm of activism, and he was eager to have his art feed directly into the tributaries that alter and quicken society's meandering flow. When he focused on the ills of society, it was not in bitterness but in the hope of eradicating these obstacles to the fulfillment of the American dream." (Prescott, 1982, p. v).

(17) Ben Shahn in Morse, 1972, p. 79.

(18) "Ben Shahn's art stood somewhere between the abstract and what is called figurative, borrowing from the one its material riches of color, shape, and texture, its explorations in form, its preference for inner organization as against outer verisimilitude, from the other its focus upon man as the center of value and as the most interesting object on earth." (Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 15)

(19) Bernarda Bryson Shahn, 1972, p. 76.

Margaret Bullock/December, 1996

Artist Objects