Edward Ruscha

American

(Omaha, Nebraska, 1937 - )

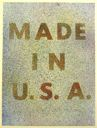

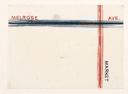

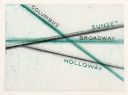

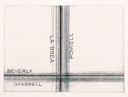

Edward Ruscha was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1937, however he, his mother, father and sister moved to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma before his fourth birthday. It was while living in Oklahoma that Ed Ruscha took his first painting class at the age of 12. He continued his study of art while enrolled in Classen High School in Oklahoma City, and began exploring typography and printing as well.(1) In 1956, Ruscha abandoned the Great Plains for the Pacific Coast, hitchhiking with a friend to Los Angeles, where he entered the Chouinard Art Institute. He studied there until 1960 and became briefly fascinated with the paintings of Abstract Expressionist artists Willem de Kooning and Franz Klein. He also saw, for the first time, the work of Pop artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.(2) His interest in the intersection of commercial and fine art was piqued by these two artists, both of whom appropriated images from popular culture and used fine art materials such as oil paints, encaustic, and bronze casting to elevate those popular, common objects. It was also during these few years in art school that Ruscha embarked on experiments that combined word paintings and collages, including SU (1958) and Sweetwater (1959), which ultimately yielded his signature style. The upper portions of these early works are mildly reminiscent of established New York artists Hans Hoffman and Mark Rothko, with painterly horizontal brushstrokes, while the bottoms of the picture plane are occupied by graphic, typeface-style lettering. After leaving Chouinard, Ruscha briefly took a job with a Los Angeles-based advertising agency. Less than one year later, Ruscha freed himself from the agency, and began a seven-month-long-tour of Europe, which included stops in England, Spain, and Paris. While traveling, he continued to test the dynamic between sterile industrial typeface fonts and painterly, evocative material applications.(3) Works such as U.S. 66 (1960) and Schwitters (1962) are examples of these intimate, small-format experiments. In London, Ruscha visited the Tate and saw J.E. Millais’ Ophelia, the strong diagonals of which he echoed in his early works such as Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights (1962) and Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (1963). In Paris, Ruscha was able to see more original artwork by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Upon his return to the United States, he also had his first encounter with the graphically-inspired art of Roy Lichtenstein.(4) His final unsuccessful attempt in the advertising field in 1961 encouraged him to commit to working on his art full-time.(5) He immediately began a series of large paintings that involved a variety of fonts painted and arranged to denote monosyllabic words. Of these, Boss (1961) and Ace (1962) are most representative, and while they are clearly rooted in his early experiments with color, collage, and typography, he moves past the meaning of the words painted on the canvas, and looks instead at the letters as decorative elements. He further challenged the viewer’s method of understanding words and images in early 1963, when he created Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western (1963). By combining these words with images, Ruscha gave them equal weight, and emphasized the objects as arbitrarily as the letters. During that same year, Ruscha unveiled his book-bound images. Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) was the first in a line of sixteen picture books that Ruscha would independently compile and publish.(6) These books provided an outlet for the artist’s tongue-in-cheek sensibility, and gave him a forum for his interest in the emerging “sprawl” culture. The factors related to urban sprawl were what Ruscha both directly and subversively tackled in pictorial narrative in these books: the necessity of the automobile, the invention of and isolation of the suburb, the growing number of highways and bypasses, the decline of traditional interstate routes, and the rise of consumerism.(7) Subsequent books focused on aspects of these same themes, including: Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1967), Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass (1968), Real Estate Opportunities (1970), Dutch Details (1971), A Few Palm Trees (1971), Colored People (1972), and his last book, Hard Light (1978). During the 15 years that Ruscha was creating bound-image, narrative books, he continued to create drawings, paintings and prints. Often times, the subject matter was directly inspired by the photographs Ruscha was creating for the books, or became a source of inspiration for the books, as in the 1965 series of graphite drawings Thayer Avenue, Doheny Drive, Wilshire Blvd., and Beverly Glen, all of which are directly related to his books Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965) and Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966).(8) His work during this period maintained his signature style: industrial typeface painted over a flat, often monochromatic, emotionally detached background. It wasn’t until 1967, when Ruscha completed his first “liquid word” painting that his style began to diverge from the hard-edged typographic mode he had used. Adios (1967), Rancho (1968), and City (1986) were painted in a trompe l’oeil mode, with the letters mimicking viscous substances. From that point, he became more interested in the quality of liquids and their relationship to art making and he began experimenting with staining paper and canvas with various liquids. His portfolio Stains (1969) included seventy-five sheets of paper that were marked or stained with various materials including bleach, chocolate syrup, and blood.(9) During that same year, he systematically rejected oil paint as a means of creating art. Ruscha recalled, “ There was a period where I couldn’t even use paint. I had to paint with unorthodox materials, so I used fruit and vegetable dyes instead of paint. I had to move some way, and the only way to do this was to stain the canvas rather than to put a skin on it.”(10) His rejection of paint continued until 1971 (11), however his fascination with “stains” found new life through his gunpowder and stain drawings such as Two Sheets Stained with Blood (1973) and Suspended Sheet Stained with Ivy (1973). His continued experiments with stained paintings such as Vanishing Cream (1973), Very Angry People (1973), and A Blvd. Called Sunset (1973) are a testament to both Ruscha’s disenchantment with traditional painting and his interest in exploring other media. The early years of the 1970s also mark Ruscha’s first professional foray into printmaking. After having worked with the Tamarind Lithography Studio in 1969, and serving as the visiting professor of printmaking at the University of California Los Angeles, he produced a series of screen prints that used staining materials instead of ink. The resulting News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews, and Dues (1970) marked Ruscha’s first major portfolio of prints, and helped to establish Ruscha as artist adept at working with multiple materials.(12) Several more print portfolios followed, including Book Covers (1970), Insects (1972), Tropical Fish (1974), and the more recent Etc., Questions & Answers, If, South (1991), Los Francisco San Angeles (2001), and Blank Signs (2004). His production of individual editioned prints, paintings, and photographs continued as well. By the early 1980s, Ed Ruscha and his artwork were being celebrated. His first major retrospective, “ The Works of Edward Ruscha” was organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1982, and traveled to three other venues in the United States and Canada. He was profiled in People magazine in 1983, and was a regularly reviewed artist in Artforum. Several more large exhibitions of his work traveled internationally, including the 1987 exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Words Without Thoughts”, the 2000 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Retrospective”, the 2006 Centre George Pompidou exhibition “Los Angeles, 1955-1985” and the 2009 retrospective organized by the Hayward Gallery in London. He continues to produce drawings, paintings, prints and photographs today, however his style has shifted significantly away from the bold typeface words he once embraced toward an absence of words using blank “placeholders” instead.(13)

(1)“Chronology”, http://edruscha.com/site/chronolgy.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009). (2)The Works of Edward Ruscha (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982), 157. (3) Neal Benezra, “ Ed Ruscha: Painting and Artistic License” in Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 149. (4) The Works of Edward Ruscha (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982), 158-159. (5) Ibid., 160. (6)Benezra, 151. (7)Phyllis Rosenzweig, “ Sixteen (and Counting): Ed Ruscha’s Books” in Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 178-186. (8)Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 36-41 . (9) Benezra, 152. (10)Ibid., 153. (11) Ibid., 153. (12) “Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Chronology”, http://www.edruscha.com/site/chronology.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009) (13) “Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Biography”, http://www.edruscha.com/site/chronology.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009).

SM 6/24/09

American

(Omaha, Nebraska, 1937 - )

Edward Ruscha was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1937, however he, his mother, father and sister moved to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma before his fourth birthday. It was while living in Oklahoma that Ed Ruscha took his first painting class at the age of 12. He continued his study of art while enrolled in Classen High School in Oklahoma City, and began exploring typography and printing as well.(1) In 1956, Ruscha abandoned the Great Plains for the Pacific Coast, hitchhiking with a friend to Los Angeles, where he entered the Chouinard Art Institute. He studied there until 1960 and became briefly fascinated with the paintings of Abstract Expressionist artists Willem de Kooning and Franz Klein. He also saw, for the first time, the work of Pop artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.(2) His interest in the intersection of commercial and fine art was piqued by these two artists, both of whom appropriated images from popular culture and used fine art materials such as oil paints, encaustic, and bronze casting to elevate those popular, common objects. It was also during these few years in art school that Ruscha embarked on experiments that combined word paintings and collages, including SU (1958) and Sweetwater (1959), which ultimately yielded his signature style. The upper portions of these early works are mildly reminiscent of established New York artists Hans Hoffman and Mark Rothko, with painterly horizontal brushstrokes, while the bottoms of the picture plane are occupied by graphic, typeface-style lettering. After leaving Chouinard, Ruscha briefly took a job with a Los Angeles-based advertising agency. Less than one year later, Ruscha freed himself from the agency, and began a seven-month-long-tour of Europe, which included stops in England, Spain, and Paris. While traveling, he continued to test the dynamic between sterile industrial typeface fonts and painterly, evocative material applications.(3) Works such as U.S. 66 (1960) and Schwitters (1962) are examples of these intimate, small-format experiments. In London, Ruscha visited the Tate and saw J.E. Millais’ Ophelia, the strong diagonals of which he echoed in his early works such as Large Trademark with Eight Spotlights (1962) and Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas (1963). In Paris, Ruscha was able to see more original artwork by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Upon his return to the United States, he also had his first encounter with the graphically-inspired art of Roy Lichtenstein.(4) His final unsuccessful attempt in the advertising field in 1961 encouraged him to commit to working on his art full-time.(5) He immediately began a series of large paintings that involved a variety of fonts painted and arranged to denote monosyllabic words. Of these, Boss (1961) and Ace (1962) are most representative, and while they are clearly rooted in his early experiments with color, collage, and typography, he moves past the meaning of the words painted on the canvas, and looks instead at the letters as decorative elements. He further challenged the viewer’s method of understanding words and images in early 1963, when he created Noise, Pencil, Broken Pencil, Cheap Western (1963). By combining these words with images, Ruscha gave them equal weight, and emphasized the objects as arbitrarily as the letters. During that same year, Ruscha unveiled his book-bound images. Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) was the first in a line of sixteen picture books that Ruscha would independently compile and publish.(6) These books provided an outlet for the artist’s tongue-in-cheek sensibility, and gave him a forum for his interest in the emerging “sprawl” culture. The factors related to urban sprawl were what Ruscha both directly and subversively tackled in pictorial narrative in these books: the necessity of the automobile, the invention of and isolation of the suburb, the growing number of highways and bypasses, the decline of traditional interstate routes, and the rise of consumerism.(7) Subsequent books focused on aspects of these same themes, including: Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965), Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1967), Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass (1968), Real Estate Opportunities (1970), Dutch Details (1971), A Few Palm Trees (1971), Colored People (1972), and his last book, Hard Light (1978). During the 15 years that Ruscha was creating bound-image, narrative books, he continued to create drawings, paintings and prints. Often times, the subject matter was directly inspired by the photographs Ruscha was creating for the books, or became a source of inspiration for the books, as in the 1965 series of graphite drawings Thayer Avenue, Doheny Drive, Wilshire Blvd., and Beverly Glen, all of which are directly related to his books Some Los Angeles Apartments (1965) and Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966).(8) His work during this period maintained his signature style: industrial typeface painted over a flat, often monochromatic, emotionally detached background. It wasn’t until 1967, when Ruscha completed his first “liquid word” painting that his style began to diverge from the hard-edged typographic mode he had used. Adios (1967), Rancho (1968), and City (1986) were painted in a trompe l’oeil mode, with the letters mimicking viscous substances. From that point, he became more interested in the quality of liquids and their relationship to art making and he began experimenting with staining paper and canvas with various liquids. His portfolio Stains (1969) included seventy-five sheets of paper that were marked or stained with various materials including bleach, chocolate syrup, and blood.(9) During that same year, he systematically rejected oil paint as a means of creating art. Ruscha recalled, “ There was a period where I couldn’t even use paint. I had to paint with unorthodox materials, so I used fruit and vegetable dyes instead of paint. I had to move some way, and the only way to do this was to stain the canvas rather than to put a skin on it.”(10) His rejection of paint continued until 1971 (11), however his fascination with “stains” found new life through his gunpowder and stain drawings such as Two Sheets Stained with Blood (1973) and Suspended Sheet Stained with Ivy (1973). His continued experiments with stained paintings such as Vanishing Cream (1973), Very Angry People (1973), and A Blvd. Called Sunset (1973) are a testament to both Ruscha’s disenchantment with traditional painting and his interest in exploring other media. The early years of the 1970s also mark Ruscha’s first professional foray into printmaking. After having worked with the Tamarind Lithography Studio in 1969, and serving as the visiting professor of printmaking at the University of California Los Angeles, he produced a series of screen prints that used staining materials instead of ink. The resulting News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews, and Dues (1970) marked Ruscha’s first major portfolio of prints, and helped to establish Ruscha as artist adept at working with multiple materials.(12) Several more print portfolios followed, including Book Covers (1970), Insects (1972), Tropical Fish (1974), and the more recent Etc., Questions & Answers, If, South (1991), Los Francisco San Angeles (2001), and Blank Signs (2004). His production of individual editioned prints, paintings, and photographs continued as well. By the early 1980s, Ed Ruscha and his artwork were being celebrated. His first major retrospective, “ The Works of Edward Ruscha” was organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1982, and traveled to three other venues in the United States and Canada. He was profiled in People magazine in 1983, and was a regularly reviewed artist in Artforum. Several more large exhibitions of his work traveled internationally, including the 1987 exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Words Without Thoughts”, the 2000 Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden exhibition “Ed Ruscha: Retrospective”, the 2006 Centre George Pompidou exhibition “Los Angeles, 1955-1985” and the 2009 retrospective organized by the Hayward Gallery in London. He continues to produce drawings, paintings, prints and photographs today, however his style has shifted significantly away from the bold typeface words he once embraced toward an absence of words using blank “placeholders” instead.(13)

(1)“Chronology”, http://edruscha.com/site/chronolgy.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009). (2)The Works of Edward Ruscha (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982), 157. (3) Neal Benezra, “ Ed Ruscha: Painting and Artistic License” in Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 149. (4) The Works of Edward Ruscha (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1982), 158-159. (5) Ibid., 160. (6)Benezra, 151. (7)Phyllis Rosenzweig, “ Sixteen (and Counting): Ed Ruscha’s Books” in Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 178-186. (8)Ed Ruscha (Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2000), 36-41 . (9) Benezra, 152. (10)Ibid., 153. (11) Ibid., 153. (12) “Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Chronology”, http://www.edruscha.com/site/chronology.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009) (13) “Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Biography”, http://www.edruscha.com/site/chronology.cfm (accessed February 23, 2009).

SM 6/24/09