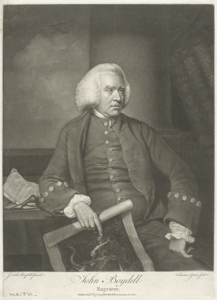

John Boydell

English

(Dorrington, England, 1719 - 1804, London, England)

lValentine Green, after painting by Josiah Boydell, Portrait of John Boydell, published 1772, mezzotint on paper, Photograph courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was a project spearheaded by printmaker and publisher John Boydell (English, 1719–1804) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in an effort to stimulate the English art market by capitalizing on the rising popularity of William Shakespeare's plays in the eighteenth century, after the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee. This Jubilee, a three-day festival organized by renowned actor David Garrick (English, 1717–1779) commemorated and celebrated the life and works of Shakespeare and demonstrated English interest in promoting visual and performing arts. (1) Shakespeare had come to dominate the English stage, and Boydell recognized this as an opportunity to create a British national school of painting with a goal to “advance that art towards maturity and establish an English School of Historical Painting.” (2)

Boydell had a lengthy artmaking and business background before conceiving his Shakespeare gallery. However, his family had little fine arts experience, as his father was a land surveyor who expected his eldest son to follow that same vocational path. (3) Instead, in his twenties Boydell became smitten with a William Henry Toms (English, 1700–1765) print engraving of Hawarden castle and decided to pursue printmaking. (4) He moved to London from Flintshire in 1740 and enrolled in St. Martin’s Lane Academy, spending the next six years working daily under Toms as his apprentice and in the Academy to master his printmaking skills.

Boydell went on to open his own print shop in 1746 along the Strand, a street running through central London known for merchandise that attracted the upper-classes. By the late 1740s, he started publishing entire books rather than individual prints and began to collect the plates of other artists to print their work instead of only his own engravings. This allowed him to become financially secure enough to marry. Boydell’s wife was Elizabeth Lloyd (British, 1739–1781), a woman whom he courted for several years. (5) Lloyd and Boydell did not have any children, and she passed away in 1781 before John’s Shakespeare Gallery venture. However, despite their own lack of children, the couple had a strong influence on the upbringing of their niece and nephew, Mary (British, 1747–1820) and Josiah Boydell (British 1752–1817), both of whom went on to have lengthy involvements in John Boydell’s work. (6)

The plan for a Shakespeare-themed gallery project initially emerged at a dinner party. Josiah Boydell decided in late 1786 to host several esteemed guests including painters Benjamin West (American, 1738–1820) and George Romney (English, 1734–1802); poet William Hayley (English, 1745–1820); scholar John Hoole (English, 1727–1803); and of course, John Boydell himself. (7) It was at this critical juncture that discussions of an arts festival arose. Josiah Boydell later wrote of John’s statement to the dinner party guests that Shakespeare was the “one great national subject” which would “excel in historical painting.” (8) According to Josiah, this proposition was met with enthusiastic approval, and thus the idea for a Shakespeare-themed gallery was born.

Prior to the inception of Boydell’s project, English art was mainly supported by commissioned portraiture. This portraiture scene was a shift from when the Catholic Church supported medieval art concerned with religion and story-telling. Around the time of Boydell’s endeavor, funding for the arts was increasingly coming from lavish royal and noble patronage that was increasingly invested in personal, self-aggrandizing pieces. (9) Some of the first esteemed portrait artists in England arose in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including portrait miniature artists Nicholas Hillard (English, 1547–1619), Isaac Oliver (English, 1565–1617), and George Gower (English, 1540–1596). (10) The interest in portrait miniatures created a market for full-sized portraits, inciting the success of portrait artists such as William Dobson (English, 1611–1646), Cornelius Johnson (English, 1593–1661), and Francis Barlow (English, 1626–1704), the “father of British sporting painting.” (11)

Going into the eighteenth century, portraiture remained extremely popular, as it was a reliable avenue for artists to make a profit. However, interest in landscape painting also emerged, along with, more notably, history painting. (12) The hierarchy of genres in figurative art, shaped in European academies since the sixteenth century and formalized by the French Academie de Peinture et Sculpture, would come to position history painting as the utmost important genre, above the popular portraits and landscapes that dominated English art at the time. (13) This emphasis on history painting was a result of the distinction between imitare, the rendering of something’s universal essence, and ritrarre, the copying of specific appearances mechanically. (14) History painting was deemed superior to all other genres of painting because it was the perfect display of imitarre, which was the highly appreciated standard at the time.

Although the art scene within England recognized the significance of history painting, John Boydell felt that foreign critics unfairly looked down upon English art in general and did not hold English-produced history painting in the proper esteem. (15) As such, Boydell sought to create a “magnificent and accurate” illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays in order to counter this perception. (16) To Boydell, this edition would give English artists the proper encouragement and subject matter to further develop a school of history painting within the nation. It is from this initial publication plan that the rest of Boydell’s project plan unfolded.

Boydell’s project plan was comprehensive; it included an illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays, a folio of engravings from these illustrations, and a gallery of the original paintings which served as models for the works in the folio. (17) He turned to some of the most prominent English artists of the time for these compositions, including English painters Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), William Hamilton (1751–1801), and Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). In total, thirty-one artists contributed works to The Folio, which included ninety-seven prints. (18) And, although Boydell’s goal was to facilitate a school of history painting, according to Burwick (1996), the primary motivation for the artists involved in Boydell’s endeavor was an interest in seeing their works engraved, published, and distributed. (19)

The gallery, designed by the architect George Dance the Younger (English, 1741–1825), was built on the Pall Mall in London with an imposing Neoclassical facade. It opened May 4, 1789, and remained in operation for sixteen years. (20) Initial critical and public response to the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was positive. Many artists involved with the venture praised the gallery, and the newspaper The Daily Advertiser reserved a column every week focusing on developments in the gallery during its quarterly exhibition cycle. (21) The Times, another popular British daily newspaper, published a review stating that the Boydell establishment “may be considered with great truth, as the first stone of an English School of Painting,” and that, in such a commercial nation as England, Boydell’s Shakespeare venture would push the country to the forefront of artistic consideration. (22)

However, as the timeline for the larger project stretched over years and costs piled up, criticism and economic challenges increased. (23) Boydell had retained relatively friendly relationships with the artists he involved in his project, but this came at a cost. James Northcote (British, 1746–1831), another painter involved with the production of the folio, wrote that Boydell paid him “more nobly than any other person has done.” (24) This liberty with the artists’ financial gratification made the entire project extremely costly and was cause for displeasure with investors. One such attack came in the form of a cartoon entitled “Boydell sacrificing the works of Shakespeare to the Devil of Money-Bags.” (25) This cartoon depicts John Boydell standing in an enchanted circle burning a pile of Shakespeare’s plays at his feet; the smoke from these burning plays contains several parodied figures from Shakespeare’s works, and to the right of the smoke is a gnome representing Avarice grasping two large bags of money.

Other criticisms attacked the gallery itself; with such a variety in artists and plays, the paintings and subsequent engravings were perceived as not thematically or aesthetically cohesive. Author Charles Lamb (English, 1775–1834) wrote that a drawback of the Shakespeare gallery was: “To have Opie's Shakespeare, Northcote's Shakespeare, light-headed Fuseli's Shakespeare, wooden-headed West's Shakespeare, deaf-headed Reynolds' Shakespeare, instead of my and everybody's Shakespeare.” (26) John Boydell had attempted to heavily promote his folio of prints to earn back the large sums of money spent on the project, taking out newspaper advertisements reading, “The encouragers of this great national undertaking will also have the satisfaction to know, that their names will be handed down to Posterity, as the Patrons of Native Genius, enrolled with their own hands, in the same book, with the best of Sovereigns.” (27) However, money earned towards the Shakespeare endeavor was not nearly enough to offset the enormous production cost of about £350,000 at the time, or about $60.3 million dollars today.

By the late 1790s, financial burdens rendered the collapse of the gallery as eminent. Subscriptions to the printed edition dropped drastically, and even those that remained were not profitable because Boydell was poor at record-keeping and failed to keep proper track of who owed payments. (28) The Boydell family had also concurrently spent large sums of money on other expansive projects that paid very little in return, such as the production of illustrated print books The Complete Works of John Milton (1794) and The History of the River Thames (1796). (29) This sent the Boydells into financial ruin and necessitated the dissolution of the Shakespeare Gallery. Boydell appealed to Parliament in 1804 for authorization of a lottery to sell off all of the items in the Boydell business. (30) All of the tickets were sold and every ticket-holder was guaranteed a print. The gallery and its painting collection ended up with a gem engraver, William Tassie (British, 1777–1860), who auctioned the paintings off at the British auction house, Christie’s. Josiah Boydell had attempted to purchase the paintings back from Tassie, but this failed and the paintings were dispersed. (31) John Boydell himself would die before the lottery was even completed. (32)

(1) Bruntjen, Sven Hermann Arnold. John Boydell (1719–1804): A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing in Georgian London. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6880-7.

(2) Collection of Prints, From Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain. London: John and Josiah Boydell, 1805

(3) Bruntjen, Sven Hermann Arnold. John Boydell (1719–1804): A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing in Georgian London. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6880-7.

(4) Clayton, Timothy. "John Boydell (1720–1804)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required). Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 0-19-861411-X.

(5) Bruntjen, 13–15

(6) Ruhlmann, Dominique. “The Beauty, the Desperate Lover and a Marriage.” The Archives and Old Library at Trinity Hall, 26 Oct. 2017, oldlibrarytrinityhall.wordpress.com/2013/02/11/the-beauty-the-desperate-lover-and-a-marriage/.

(7) Santaniello, A. E. "Introduction". The Boydell Shakespeare Prints. New York: Benjamin Bloom, 1968.

(8) Friedman, Winifred H. Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1976. ISBN 0-8240-1987-3.

(9) "Charles I art collection reunited for first time in 350 years as Royal Academy relocates works from Van Dyke and Titian". The Daily Telegraph.

(10) "Small is beautiful". The Daily Telegraph.

(11) Artworks by or after English art, Art UK.

(12) "Painting history: Manet on a mission". The Daily Telegraph.

(13) Belton, Dr. Robert J. (1996). "The Elements of Art". Art History: A Preliminary Handbook.

(14) Bass, Laura L.,The Drama of the Portrait: Theater and Visual Culture in Early Modern Spain, Penn State Press, 2008, ISBN 0-271-03304-5, ISBN 978-0-271-03304-4

(15) Friedman, 4–5.

(16) Collection of Prints, From Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, by the Artists of

(17) Santaniello, A. E. "Introduction". The Boydell Shakespeare Prints. New York: Benjamin Bloom, 1968.

(18) Boase, T.S.R. "Illustrations of Shakespeare's Plays in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 10 (1947): 83–108

(19) Burwick, Frederick. "Introduction: The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Archived 27 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine". The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Eds. Walter Pape and Frederick Burwick. Bottrop, Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1996. ISBN 3-89355-134-4.

(20) Sheppard, F.H.W. Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster, Part 1. London: Athlone Press for London County Council, 1960.

(21) Bruntjen, 92.

(22) Friedman, Winifred H. Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1976. ISBN 0-8240-1987-3

(23) Friedman, 84.

(24) Hartmann, Sadakichi. Shakespeare in Art. Art Lovers' Series. Boston: L. C. Page & Co., 1901.

(25) Merchant, W. Moelwyn. Shakespeare and the Artist. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

(26) Merchant, 67.

(27) Friedman, 85–86.

(28) Lennox-Boyd, Christopher. "The Prints Themselves: Production, Marketing, and their Survival". The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Eds. Walter Pape and Frederick Burwick. Bottrop, Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1996. ISBN 3-89355-134-4.

(29) Bruntjen, 113.

(30) "No. 15752". The London Gazette. 6 November 1804. p. 1368.

(31) Friedman, 4, 87–90

(32) “John Boydell.” National Portrait Gallery, www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp00520/john-boydell.

English

(Dorrington, England, 1719 - 1804, London, England)

lValentine Green, after painting by Josiah Boydell, Portrait of John Boydell, published 1772, mezzotint on paper, Photograph courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was a project spearheaded by printmaker and publisher John Boydell (English, 1719–1804) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in an effort to stimulate the English art market by capitalizing on the rising popularity of William Shakespeare's plays in the eighteenth century, after the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee. This Jubilee, a three-day festival organized by renowned actor David Garrick (English, 1717–1779) commemorated and celebrated the life and works of Shakespeare and demonstrated English interest in promoting visual and performing arts. (1) Shakespeare had come to dominate the English stage, and Boydell recognized this as an opportunity to create a British national school of painting with a goal to “advance that art towards maturity and establish an English School of Historical Painting.” (2)

Boydell had a lengthy artmaking and business background before conceiving his Shakespeare gallery. However, his family had little fine arts experience, as his father was a land surveyor who expected his eldest son to follow that same vocational path. (3) Instead, in his twenties Boydell became smitten with a William Henry Toms (English, 1700–1765) print engraving of Hawarden castle and decided to pursue printmaking. (4) He moved to London from Flintshire in 1740 and enrolled in St. Martin’s Lane Academy, spending the next six years working daily under Toms as his apprentice and in the Academy to master his printmaking skills.

Boydell went on to open his own print shop in 1746 along the Strand, a street running through central London known for merchandise that attracted the upper-classes. By the late 1740s, he started publishing entire books rather than individual prints and began to collect the plates of other artists to print their work instead of only his own engravings. This allowed him to become financially secure enough to marry. Boydell’s wife was Elizabeth Lloyd (British, 1739–1781), a woman whom he courted for several years. (5) Lloyd and Boydell did not have any children, and she passed away in 1781 before John’s Shakespeare Gallery venture. However, despite their own lack of children, the couple had a strong influence on the upbringing of their niece and nephew, Mary (British, 1747–1820) and Josiah Boydell (British 1752–1817), both of whom went on to have lengthy involvements in John Boydell’s work. (6)

The plan for a Shakespeare-themed gallery project initially emerged at a dinner party. Josiah Boydell decided in late 1786 to host several esteemed guests including painters Benjamin West (American, 1738–1820) and George Romney (English, 1734–1802); poet William Hayley (English, 1745–1820); scholar John Hoole (English, 1727–1803); and of course, John Boydell himself. (7) It was at this critical juncture that discussions of an arts festival arose. Josiah Boydell later wrote of John’s statement to the dinner party guests that Shakespeare was the “one great national subject” which would “excel in historical painting.” (8) According to Josiah, this proposition was met with enthusiastic approval, and thus the idea for a Shakespeare-themed gallery was born.

Prior to the inception of Boydell’s project, English art was mainly supported by commissioned portraiture. This portraiture scene was a shift from when the Catholic Church supported medieval art concerned with religion and story-telling. Around the time of Boydell’s endeavor, funding for the arts was increasingly coming from lavish royal and noble patronage that was increasingly invested in personal, self-aggrandizing pieces. (9) Some of the first esteemed portrait artists in England arose in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including portrait miniature artists Nicholas Hillard (English, 1547–1619), Isaac Oliver (English, 1565–1617), and George Gower (English, 1540–1596). (10) The interest in portrait miniatures created a market for full-sized portraits, inciting the success of portrait artists such as William Dobson (English, 1611–1646), Cornelius Johnson (English, 1593–1661), and Francis Barlow (English, 1626–1704), the “father of British sporting painting.” (11)

Going into the eighteenth century, portraiture remained extremely popular, as it was a reliable avenue for artists to make a profit. However, interest in landscape painting also emerged, along with, more notably, history painting. (12) The hierarchy of genres in figurative art, shaped in European academies since the sixteenth century and formalized by the French Academie de Peinture et Sculpture, would come to position history painting as the utmost important genre, above the popular portraits and landscapes that dominated English art at the time. (13) This emphasis on history painting was a result of the distinction between imitare, the rendering of something’s universal essence, and ritrarre, the copying of specific appearances mechanically. (14) History painting was deemed superior to all other genres of painting because it was the perfect display of imitarre, which was the highly appreciated standard at the time.

Although the art scene within England recognized the significance of history painting, John Boydell felt that foreign critics unfairly looked down upon English art in general and did not hold English-produced history painting in the proper esteem. (15) As such, Boydell sought to create a “magnificent and accurate” illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays in order to counter this perception. (16) To Boydell, this edition would give English artists the proper encouragement and subject matter to further develop a school of history painting within the nation. It is from this initial publication plan that the rest of Boydell’s project plan unfolded.

Boydell’s project plan was comprehensive; it included an illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s plays, a folio of engravings from these illustrations, and a gallery of the original paintings which served as models for the works in the folio. (17) He turned to some of the most prominent English artists of the time for these compositions, including English painters Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), William Hamilton (1751–1801), and Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). In total, thirty-one artists contributed works to The Folio, which included ninety-seven prints. (18) And, although Boydell’s goal was to facilitate a school of history painting, according to Burwick (1996), the primary motivation for the artists involved in Boydell’s endeavor was an interest in seeing their works engraved, published, and distributed. (19)

The gallery, designed by the architect George Dance the Younger (English, 1741–1825), was built on the Pall Mall in London with an imposing Neoclassical facade. It opened May 4, 1789, and remained in operation for sixteen years. (20) Initial critical and public response to the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery was positive. Many artists involved with the venture praised the gallery, and the newspaper The Daily Advertiser reserved a column every week focusing on developments in the gallery during its quarterly exhibition cycle. (21) The Times, another popular British daily newspaper, published a review stating that the Boydell establishment “may be considered with great truth, as the first stone of an English School of Painting,” and that, in such a commercial nation as England, Boydell’s Shakespeare venture would push the country to the forefront of artistic consideration. (22)

However, as the timeline for the larger project stretched over years and costs piled up, criticism and economic challenges increased. (23) Boydell had retained relatively friendly relationships with the artists he involved in his project, but this came at a cost. James Northcote (British, 1746–1831), another painter involved with the production of the folio, wrote that Boydell paid him “more nobly than any other person has done.” (24) This liberty with the artists’ financial gratification made the entire project extremely costly and was cause for displeasure with investors. One such attack came in the form of a cartoon entitled “Boydell sacrificing the works of Shakespeare to the Devil of Money-Bags.” (25) This cartoon depicts John Boydell standing in an enchanted circle burning a pile of Shakespeare’s plays at his feet; the smoke from these burning plays contains several parodied figures from Shakespeare’s works, and to the right of the smoke is a gnome representing Avarice grasping two large bags of money.

Other criticisms attacked the gallery itself; with such a variety in artists and plays, the paintings and subsequent engravings were perceived as not thematically or aesthetically cohesive. Author Charles Lamb (English, 1775–1834) wrote that a drawback of the Shakespeare gallery was: “To have Opie's Shakespeare, Northcote's Shakespeare, light-headed Fuseli's Shakespeare, wooden-headed West's Shakespeare, deaf-headed Reynolds' Shakespeare, instead of my and everybody's Shakespeare.” (26) John Boydell had attempted to heavily promote his folio of prints to earn back the large sums of money spent on the project, taking out newspaper advertisements reading, “The encouragers of this great national undertaking will also have the satisfaction to know, that their names will be handed down to Posterity, as the Patrons of Native Genius, enrolled with their own hands, in the same book, with the best of Sovereigns.” (27) However, money earned towards the Shakespeare endeavor was not nearly enough to offset the enormous production cost of about £350,000 at the time, or about $60.3 million dollars today.

By the late 1790s, financial burdens rendered the collapse of the gallery as eminent. Subscriptions to the printed edition dropped drastically, and even those that remained were not profitable because Boydell was poor at record-keeping and failed to keep proper track of who owed payments. (28) The Boydell family had also concurrently spent large sums of money on other expansive projects that paid very little in return, such as the production of illustrated print books The Complete Works of John Milton (1794) and The History of the River Thames (1796). (29) This sent the Boydells into financial ruin and necessitated the dissolution of the Shakespeare Gallery. Boydell appealed to Parliament in 1804 for authorization of a lottery to sell off all of the items in the Boydell business. (30) All of the tickets were sold and every ticket-holder was guaranteed a print. The gallery and its painting collection ended up with a gem engraver, William Tassie (British, 1777–1860), who auctioned the paintings off at the British auction house, Christie’s. Josiah Boydell had attempted to purchase the paintings back from Tassie, but this failed and the paintings were dispersed. (31) John Boydell himself would die before the lottery was even completed. (32)

(1) Bruntjen, Sven Hermann Arnold. John Boydell (1719–1804): A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing in Georgian London. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6880-7.

(2) Collection of Prints, From Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, by the Artists of Great-Britain. London: John and Josiah Boydell, 1805

(3) Bruntjen, Sven Hermann Arnold. John Boydell (1719–1804): A Study of Art Patronage and Publishing in Georgian London. New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6880-7.

(4) Clayton, Timothy. "John Boydell (1720–1804)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required). Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 0-19-861411-X.

(5) Bruntjen, 13–15

(6) Ruhlmann, Dominique. “The Beauty, the Desperate Lover and a Marriage.” The Archives and Old Library at Trinity Hall, 26 Oct. 2017, oldlibrarytrinityhall.wordpress.com/2013/02/11/the-beauty-the-desperate-lover-and-a-marriage/.

(7) Santaniello, A. E. "Introduction". The Boydell Shakespeare Prints. New York: Benjamin Bloom, 1968.

(8) Friedman, Winifred H. Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1976. ISBN 0-8240-1987-3.

(9) "Charles I art collection reunited for first time in 350 years as Royal Academy relocates works from Van Dyke and Titian". The Daily Telegraph.

(10) "Small is beautiful". The Daily Telegraph.

(11) Artworks by or after English art, Art UK.

(12) "Painting history: Manet on a mission". The Daily Telegraph.

(13) Belton, Dr. Robert J. (1996). "The Elements of Art". Art History: A Preliminary Handbook.

(14) Bass, Laura L.,The Drama of the Portrait: Theater and Visual Culture in Early Modern Spain, Penn State Press, 2008, ISBN 0-271-03304-5, ISBN 978-0-271-03304-4

(15) Friedman, 4–5.

(16) Collection of Prints, From Pictures Painted for the Purpose of Illustrating the Dramatic Works of Shakespeare, by the Artists of

(17) Santaniello, A. E. "Introduction". The Boydell Shakespeare Prints. New York: Benjamin Bloom, 1968.

(18) Boase, T.S.R. "Illustrations of Shakespeare's Plays in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 10 (1947): 83–108

(19) Burwick, Frederick. "Introduction: The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Archived 27 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine". The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Eds. Walter Pape and Frederick Burwick. Bottrop, Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1996. ISBN 3-89355-134-4.

(20) Sheppard, F.H.W. Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster, Part 1. London: Athlone Press for London County Council, 1960.

(21) Bruntjen, 92.

(22) Friedman, Winifred H. Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1976. ISBN 0-8240-1987-3

(23) Friedman, 84.

(24) Hartmann, Sadakichi. Shakespeare in Art. Art Lovers' Series. Boston: L. C. Page & Co., 1901.

(25) Merchant, W. Moelwyn. Shakespeare and the Artist. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

(26) Merchant, 67.

(27) Friedman, 85–86.

(28) Lennox-Boyd, Christopher. "The Prints Themselves: Production, Marketing, and their Survival". The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Eds. Walter Pape and Frederick Burwick. Bottrop, Essen: Verlag Peter Pomp, 1996. ISBN 3-89355-134-4.

(29) Bruntjen, 113.

(30) "No. 15752". The London Gazette. 6 November 1804. p. 1368.

(31) Friedman, 4, 87–90

(32) “John Boydell.” National Portrait Gallery, www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp00520/john-boydell.

Artist Objects