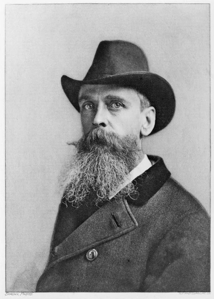

Thomas Moran

American, born England

(Bolton, England, 1837 - 1926, Santa Barbara, California)

“I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature. My general scope is not realistic: all my tendencies are toward idealization. Of course, all art must come through Nature; but I believe a place, as a place, has no value in itself for the artist only so far as it furnishes the material from which to construct a picture.”

—Thomas Moran

In the 1840s, a group of expansionists affiliated with the Democratic Party began to call themselves the “Young America” movement, proclaiming that it was the “Manifest Destiny” of the United States to grow from sea to sea, from the Arctic Circle to the Tropics. In an 1845 issue of "Democratic Review," John L. O’Sullivan wrote that it is “our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty.”(1) By the 1850s, tourism was a booming business. As early as the 1820s, wealthy Americans began to travel for the sole purpose of looking at scenery. Improved transportation (specifically the railroad), disposable time and money made such journeys possible. Surveying became an indispensable component of United States official policy. The government, taking an active part in expansion and exploration since the Lewis and Clarke expedition at the turn of the century, continued to support journeys west so that scientists, the military, and others could begin to record and document unchartered territories.

From 1867-79, there were four major expeditions, called the “Great Surveys,” because of their wide geographical range, their long duration, and their comprehensive research. Directed by civilians under the Departments of War, Interior, and the Smithsonian, scientists and documenters recorded the landscape and collected samples of flora and fauna. Surveyors realized that text descriptions fell short of describing the actual landscape and artists and photographers became a necessary addition to the expeditions. Traditional watercolors and oils were exceptionally useful to survey leaders lobbying Congress. Thomas Moran was one of many artists who were included in these “Great Surveys.” In fact, Moran’s sketches and paintings of the Yellowstone aided in its establishment as a national park. Moran created enormous paintings of the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon that fueled American thirst for exploration of the frontier. Not only did he capture magnificent vistas, but he also documented the natural history of the United States.

Thomas Moran was the fifth child born to Thomas and Mary Moran in Lancashire, England in 1837. The 1830s were an unfortunate time for the Morans, due to the social dislocation engendered by Industrial Revolution.(2) Bleak living conditions, poor work prospects, and a growing family were undoubtedly critical factors in their decision to immigrate to America. However, according to Thomas’ mother, the immediate impetus came from visiting American artist, George Catlin (1796-1892). The famous Indian painter lectured regularly on North American Indian life and other topics.(3) It is unknown what comments by Catlin convinced Moran’s father, but in 1842, the family set sail for America.

Once in the United States, the Morans settled in Kensington, a working class district of Philadelphia. In 1853, Moran entered into an apprenticeship with Scattergood & Telfer, a Philadelphia engraving firm. His brother, Edward, was an artist as well, and debuted at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1854.(4) Moran remained at Scattergood and Teller for two years before he quit in order to work in his brother’s studio.

During the brothers' early years in Philadelphia, the pair received valuable professional and personal advice from Paul Weber (1823-1916) and James Hamilton (1819-1878). Weber was a German landscapist who had traveled extensively in the Northeast and painted works saturated with the rich colors and textures of the American forests, especially those surrounding Philadelphia. Moran’s early works, including the Museum’s "Dusk Wings" (1860), closely resemble Weber’s paintings. After Weber’s return to Europe in 1861, Moran then began to work with James Hamilton.

Hamilton immigrated to the United States at fifteen, and once in Philadelphia, sought out well-known engraver, John Sartain (1808-1897). Soon after their meeting, Sartain took Hamilton as a student and began instructing him in drawing. Sartain described Hamilton as a devoted student to English landscape painter Joseph William Mallard Turner (1775-1852). Hamilton soon traveled to London to study Turner’s works firsthand and was later dubbed an “American Turner.” It was Hamilton who introduced Moran to Turner’s work through a large collection of books and prints. As a result, Turner would be the greatest influence upon Moran throughout his career.

Turner studied nature firsthand, taking his sketchbooks with him on trips throughout England, Scotland, Wales, and the Continent. While he sometimes sketched or painted out of doors, he produced more complete works in the studio and there he finished pieces intended for reproduction, exhibition, or sale. Major works on canvas painted in the studio were based on numerous pencil and watercolor sketches as well as on his devoted study of the Old Masters.

Moran paid homage to Turner by copying his greatest works, and he also obtained a copy Turner’s "Liber Studiorum (Book of Studies or Drawing Book)" (1802-5). Ninety-one plates illustrate Turner’s range as an artist and it was a critical tool in Moran’s early study of nature. In the spring of 1862, Moran and his brother Edward, decided to travel to England where they could view and study the master’s works first hand.

Upon his arrival in London, Moran went straight to the National Gallery to examine Turner’s paintings. According to family legend, Moran haunted the Gallery for weeks, studying and copying his paintings. Turner’s color palette had an enormous impact on Moran, which was soon evident in his paintings and sketches of the American West. Moran also discovered that Turner’s landscapes were not literal depictions of actual sites. In an attempt to explore Turner’s methods, Moran traveled to various sites the elder artist painted in England, only to realize Turner had pieced together elements of landscapes to create his own impression of nature. As a result, Moran had little interest in topographical accuracy and his great paintings were often a combination of various vantage points.

Moran and his brother returned to the United States in the fall of 1862. The following year, Moran married Mary Nemmo, who taught drawing out of their home. She became her husband’s business partner and was an accomplished engraver. Mary was later responsible for coordinating details for a staggering number of commissions Moran received for periodical illustrations. In 1866, the couple and their young son, Paul, sailed for Europe where they remained for much of the following year. By this time, Moran was exhibiting regularly at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and around 1870 began illustrating for "Scribner’s Monthly."

In 1870, Richard Watson Gilder, the managing editor of "Scribner’s," commissioned Moran to rework a number of amateur field sketches that were to accompany an article by Nathaniel P. Langford about Yellowstone. Moran immediately recognized the opportunity and was resourceful enough to find a way to visit Yellowstone a few months later. Perhaps another impetus for Moran’s journey was Albert Bierstadt. Moran saw Bierstadt, who was creating magnificent landscapes of the Rocky Mountains, as competition. Bierstadt had not yet been to sketch Yellowstone, and the speed at which Moran arrived there suggests that he was well aware of the lucrative market Bierstadt had created for magnificent vistas of the American West. Furthermore, a large scale painting of a relatively unknown western land might reap financial rewards.

In the summer of 1871, geologist F. V. Hayden was in his fifth year of surveying the Yellowstone region when Moran joined his expedition. Hayden employed graphic artists and photographers, being well aware of their importance for his success and for portraying the West. Also on the expedition was photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942). Moran and Jackson worked together in selecting views and developing ideas for their respective images. While oil sketches in the field were excellent for making notions of light and color, photographs were equally important as to documenting exact locations and details when time would otherwise not allow.

When Moran returned to New Jersey after the expedition he immediately began work on a massive landscape of Yellowstone while Hayden was lobbying Congress to turn the area into a national park. When the bill was passed, Jackson reportedly wrote that “the watercolors of Thomas Moran and the photographs of the Geology Survey [Jackson’s] were the most important exhibits brought before the committee.”(5) Shortly thereafter, Moran was anxious to get the painting completed.

Two months after the Yellowstone Park Bill passed in May 1872, Moran exhibited "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" (1872, Department of the Interior) at the Smithsonian. Almost immediately Moran began lobbying for exhibition space in the Capitol. Less than two weeks later Congress purchased the painting for $10,000 and the work was hung in the old Hall of Representatives. At the same time, Moran was entertaining an invitation to join Major John Wesley Powell on an expedition from Chicago to Salt Lake City. The expedition included a visit to the Grand Canyon, which would be Moran’s next major painting. Like "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone," "Chasm of the Colorado" (1873-74, Department of the Interior Museum) was also bought by the United States government.

Moran’s third panoramic painting was "Mountain of the Holy Cross" (1875, Autry Museum of Western Heritage). The Mountain of the Holy Cross was a legendary place in the nineteenth century. Moran had seen photographs, but few had actually seen this Colorado mountain, whose crevices, when filled with snow, formed a holy cross. In August of 1873, Moran and Jackson traveled to visit and document the range. By September, Moran returned to New York to complete the painting and prepare for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The artist’s original plan was to borrow "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" and "Chasm of the Colorado" from Congress and exhibit them with "Mountain of the Holy Cross" at the Centennial. However, Congress declined the loan of the first two works.

"Mountain of the Holy Cross" was bought in early 1880 by Dr. William Bell, an English physician and railroad entrepreneur. Bell was a founding member of the consortium that built the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, a line that ran between Denver and Mexico City. Like many others, Bell saw prosperity in luring passengers if they could stop at sights along the rail line. He saw profit in promoting the therapeutic properties of mineral water located at Colorado Springs and Manitou, two newly established communities on the rail line south of Denver. Bell installed the painting at Manitou. The painting, which depicted the mountain with a cascading waterfall below, created an image in which “holy” water seemed to be streaming from the mountain with the cross of snow. As a result, Bell hoped to cash in on the spiritual and physical healing powers the water might have on his clientele.

Throughout the remainder of his career, Moran continued to travel west and created dazzling landscapes of a quickly diminishing frontier. His trips included visits to Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Mexico. However, perhaps one of his most important trips from a personal standpoint was that to Venice, Italy, where he was able to trace Turner’s steps in capturing the canals and romance of the venerable city. By 1899, Moran had lost his wife from an illness she had contracted while nursing soldiers during the Spanish American War. From this point on until his death in 1926, his daughter Ruth accompanied him on summer trips to the Grand Canyon where they wintered.

(1) John L. O’Sullivan, editor of "Democratic Review," 1845, quoted in John M. Murrin, et al., "Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People" (Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1996): 435.

(2) A large number of workers found themselves unemployed after they were replaced by machines that could do the job quicker and cheaper. The textile industry felt this impact the hardest, as the introduction of the spinning jenny and power loom quickly transformed a domestic craft into a factory industry. Moran’s parents, descendents of a long line of hand-loom weavers, were caught in the midst. For more, see Nancy K. Anderson, "Thomas Moran" (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998):20-23.

(3) Anderson explains that Catlin arrived in London in 1840 in a fit of anger after Congress failed to purchase the Indian paintings and artifacts that he called his “Indian Gallery.” Threatening to send his collection abroad, Catlin installed the Indian Gallery in London’s Egyptian Hall.

(4) Moran said many years later that his brother taught him about art and grounded him in the principles he had worked on his entire life. Furthermore, he said that he probably wouldn’t have been a painter if it hadn’t been for Edward’s encouragement and assistance.

(5) Anderson, 53.

- Letha Clair Robertson , 2/2/04/rev.mla.3.31.08

Image credit: Napoleon Sarony (American, born Canada, 1821–1896), Thomas Moran, between 1890 and 1896, photogravure, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., [LC-USZ62-115323]

American, born England

(Bolton, England, 1837 - 1926, Santa Barbara, California)

“I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature. My general scope is not realistic: all my tendencies are toward idealization. Of course, all art must come through Nature; but I believe a place, as a place, has no value in itself for the artist only so far as it furnishes the material from which to construct a picture.”

—Thomas Moran

In the 1840s, a group of expansionists affiliated with the Democratic Party began to call themselves the “Young America” movement, proclaiming that it was the “Manifest Destiny” of the United States to grow from sea to sea, from the Arctic Circle to the Tropics. In an 1845 issue of "Democratic Review," John L. O’Sullivan wrote that it is “our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty.”(1) By the 1850s, tourism was a booming business. As early as the 1820s, wealthy Americans began to travel for the sole purpose of looking at scenery. Improved transportation (specifically the railroad), disposable time and money made such journeys possible. Surveying became an indispensable component of United States official policy. The government, taking an active part in expansion and exploration since the Lewis and Clarke expedition at the turn of the century, continued to support journeys west so that scientists, the military, and others could begin to record and document unchartered territories.

From 1867-79, there were four major expeditions, called the “Great Surveys,” because of their wide geographical range, their long duration, and their comprehensive research. Directed by civilians under the Departments of War, Interior, and the Smithsonian, scientists and documenters recorded the landscape and collected samples of flora and fauna. Surveyors realized that text descriptions fell short of describing the actual landscape and artists and photographers became a necessary addition to the expeditions. Traditional watercolors and oils were exceptionally useful to survey leaders lobbying Congress. Thomas Moran was one of many artists who were included in these “Great Surveys.” In fact, Moran’s sketches and paintings of the Yellowstone aided in its establishment as a national park. Moran created enormous paintings of the Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon that fueled American thirst for exploration of the frontier. Not only did he capture magnificent vistas, but he also documented the natural history of the United States.

Thomas Moran was the fifth child born to Thomas and Mary Moran in Lancashire, England in 1837. The 1830s were an unfortunate time for the Morans, due to the social dislocation engendered by Industrial Revolution.(2) Bleak living conditions, poor work prospects, and a growing family were undoubtedly critical factors in their decision to immigrate to America. However, according to Thomas’ mother, the immediate impetus came from visiting American artist, George Catlin (1796-1892). The famous Indian painter lectured regularly on North American Indian life and other topics.(3) It is unknown what comments by Catlin convinced Moran’s father, but in 1842, the family set sail for America.

Once in the United States, the Morans settled in Kensington, a working class district of Philadelphia. In 1853, Moran entered into an apprenticeship with Scattergood & Telfer, a Philadelphia engraving firm. His brother, Edward, was an artist as well, and debuted at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1854.(4) Moran remained at Scattergood and Teller for two years before he quit in order to work in his brother’s studio.

During the brothers' early years in Philadelphia, the pair received valuable professional and personal advice from Paul Weber (1823-1916) and James Hamilton (1819-1878). Weber was a German landscapist who had traveled extensively in the Northeast and painted works saturated with the rich colors and textures of the American forests, especially those surrounding Philadelphia. Moran’s early works, including the Museum’s "Dusk Wings" (1860), closely resemble Weber’s paintings. After Weber’s return to Europe in 1861, Moran then began to work with James Hamilton.

Hamilton immigrated to the United States at fifteen, and once in Philadelphia, sought out well-known engraver, John Sartain (1808-1897). Soon after their meeting, Sartain took Hamilton as a student and began instructing him in drawing. Sartain described Hamilton as a devoted student to English landscape painter Joseph William Mallard Turner (1775-1852). Hamilton soon traveled to London to study Turner’s works firsthand and was later dubbed an “American Turner.” It was Hamilton who introduced Moran to Turner’s work through a large collection of books and prints. As a result, Turner would be the greatest influence upon Moran throughout his career.

Turner studied nature firsthand, taking his sketchbooks with him on trips throughout England, Scotland, Wales, and the Continent. While he sometimes sketched or painted out of doors, he produced more complete works in the studio and there he finished pieces intended for reproduction, exhibition, or sale. Major works on canvas painted in the studio were based on numerous pencil and watercolor sketches as well as on his devoted study of the Old Masters.

Moran paid homage to Turner by copying his greatest works, and he also obtained a copy Turner’s "Liber Studiorum (Book of Studies or Drawing Book)" (1802-5). Ninety-one plates illustrate Turner’s range as an artist and it was a critical tool in Moran’s early study of nature. In the spring of 1862, Moran and his brother Edward, decided to travel to England where they could view and study the master’s works first hand.

Upon his arrival in London, Moran went straight to the National Gallery to examine Turner’s paintings. According to family legend, Moran haunted the Gallery for weeks, studying and copying his paintings. Turner’s color palette had an enormous impact on Moran, which was soon evident in his paintings and sketches of the American West. Moran also discovered that Turner’s landscapes were not literal depictions of actual sites. In an attempt to explore Turner’s methods, Moran traveled to various sites the elder artist painted in England, only to realize Turner had pieced together elements of landscapes to create his own impression of nature. As a result, Moran had little interest in topographical accuracy and his great paintings were often a combination of various vantage points.

Moran and his brother returned to the United States in the fall of 1862. The following year, Moran married Mary Nemmo, who taught drawing out of their home. She became her husband’s business partner and was an accomplished engraver. Mary was later responsible for coordinating details for a staggering number of commissions Moran received for periodical illustrations. In 1866, the couple and their young son, Paul, sailed for Europe where they remained for much of the following year. By this time, Moran was exhibiting regularly at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and around 1870 began illustrating for "Scribner’s Monthly."

In 1870, Richard Watson Gilder, the managing editor of "Scribner’s," commissioned Moran to rework a number of amateur field sketches that were to accompany an article by Nathaniel P. Langford about Yellowstone. Moran immediately recognized the opportunity and was resourceful enough to find a way to visit Yellowstone a few months later. Perhaps another impetus for Moran’s journey was Albert Bierstadt. Moran saw Bierstadt, who was creating magnificent landscapes of the Rocky Mountains, as competition. Bierstadt had not yet been to sketch Yellowstone, and the speed at which Moran arrived there suggests that he was well aware of the lucrative market Bierstadt had created for magnificent vistas of the American West. Furthermore, a large scale painting of a relatively unknown western land might reap financial rewards.

In the summer of 1871, geologist F. V. Hayden was in his fifth year of surveying the Yellowstone region when Moran joined his expedition. Hayden employed graphic artists and photographers, being well aware of their importance for his success and for portraying the West. Also on the expedition was photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942). Moran and Jackson worked together in selecting views and developing ideas for their respective images. While oil sketches in the field were excellent for making notions of light and color, photographs were equally important as to documenting exact locations and details when time would otherwise not allow.

When Moran returned to New Jersey after the expedition he immediately began work on a massive landscape of Yellowstone while Hayden was lobbying Congress to turn the area into a national park. When the bill was passed, Jackson reportedly wrote that “the watercolors of Thomas Moran and the photographs of the Geology Survey [Jackson’s] were the most important exhibits brought before the committee.”(5) Shortly thereafter, Moran was anxious to get the painting completed.

Two months after the Yellowstone Park Bill passed in May 1872, Moran exhibited "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" (1872, Department of the Interior) at the Smithsonian. Almost immediately Moran began lobbying for exhibition space in the Capitol. Less than two weeks later Congress purchased the painting for $10,000 and the work was hung in the old Hall of Representatives. At the same time, Moran was entertaining an invitation to join Major John Wesley Powell on an expedition from Chicago to Salt Lake City. The expedition included a visit to the Grand Canyon, which would be Moran’s next major painting. Like "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone," "Chasm of the Colorado" (1873-74, Department of the Interior Museum) was also bought by the United States government.

Moran’s third panoramic painting was "Mountain of the Holy Cross" (1875, Autry Museum of Western Heritage). The Mountain of the Holy Cross was a legendary place in the nineteenth century. Moran had seen photographs, but few had actually seen this Colorado mountain, whose crevices, when filled with snow, formed a holy cross. In August of 1873, Moran and Jackson traveled to visit and document the range. By September, Moran returned to New York to complete the painting and prepare for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The artist’s original plan was to borrow "Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone" and "Chasm of the Colorado" from Congress and exhibit them with "Mountain of the Holy Cross" at the Centennial. However, Congress declined the loan of the first two works.

"Mountain of the Holy Cross" was bought in early 1880 by Dr. William Bell, an English physician and railroad entrepreneur. Bell was a founding member of the consortium that built the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, a line that ran between Denver and Mexico City. Like many others, Bell saw prosperity in luring passengers if they could stop at sights along the rail line. He saw profit in promoting the therapeutic properties of mineral water located at Colorado Springs and Manitou, two newly established communities on the rail line south of Denver. Bell installed the painting at Manitou. The painting, which depicted the mountain with a cascading waterfall below, created an image in which “holy” water seemed to be streaming from the mountain with the cross of snow. As a result, Bell hoped to cash in on the spiritual and physical healing powers the water might have on his clientele.

Throughout the remainder of his career, Moran continued to travel west and created dazzling landscapes of a quickly diminishing frontier. His trips included visits to Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, and Mexico. However, perhaps one of his most important trips from a personal standpoint was that to Venice, Italy, where he was able to trace Turner’s steps in capturing the canals and romance of the venerable city. By 1899, Moran had lost his wife from an illness she had contracted while nursing soldiers during the Spanish American War. From this point on until his death in 1926, his daughter Ruth accompanied him on summer trips to the Grand Canyon where they wintered.

(1) John L. O’Sullivan, editor of "Democratic Review," 1845, quoted in John M. Murrin, et al., "Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People" (Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1996): 435.

(2) A large number of workers found themselves unemployed after they were replaced by machines that could do the job quicker and cheaper. The textile industry felt this impact the hardest, as the introduction of the spinning jenny and power loom quickly transformed a domestic craft into a factory industry. Moran’s parents, descendents of a long line of hand-loom weavers, were caught in the midst. For more, see Nancy K. Anderson, "Thomas Moran" (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998):20-23.

(3) Anderson explains that Catlin arrived in London in 1840 in a fit of anger after Congress failed to purchase the Indian paintings and artifacts that he called his “Indian Gallery.” Threatening to send his collection abroad, Catlin installed the Indian Gallery in London’s Egyptian Hall.

(4) Moran said many years later that his brother taught him about art and grounded him in the principles he had worked on his entire life. Furthermore, he said that he probably wouldn’t have been a painter if it hadn’t been for Edward’s encouragement and assistance.

(5) Anderson, 53.

- Letha Clair Robertson , 2/2/04/rev.mla.3.31.08

Image credit: Napoleon Sarony (American, born Canada, 1821–1896), Thomas Moran, between 1890 and 1896, photogravure, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., [LC-USZ62-115323]