Thomas Hart Benton

American

(Neosho, Missouri, 1889 - 1975, Kansas City, Missouri)

Thomas Hart Benton was a controversial and influential character in both the art and social worlds in early and mid-twentieth century America. He was born on April 15th, 1889 in Neosho, Newton County, Missouri into that state’s most politically powerful family. His great-uncle, also named Thomas Hart Benton, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1820 when Missouri became a state. His father, “Colonel” Maecenas Eason Benton (called M.E.), was a U.S. district attorney for Missouri and was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1896. During his father’s time in Congress, 1897-1905, Benton lived in Washington D.C. He finished grade school there, and was first introduced to an appreciation of fine art at the Library of Congress and the Corcoran Gallery during this time. He also studied art for the first time in Washington D.C. at Western High School in Georgetown. In the March 1, 1937 issue of Life magazine, an article titled “Thomas Benton Paints a History of His Own Missouri,” suggested that Benton’s family history had much to do with his success as an artist: “The Bentons of Missouri are that state’s most revered political family. Missourians say that if Tom Benton were not a Benton he never could get away with such unconventional murals” (Gruber 13). It does seem that Benton’s heritage influenced the way in which he approached his career. As a campaigning politician might do, he made certain that his name and theories of art were publically known and promoted. Through his outspokenness, writings, and large-scale public mural projects, Benton became known as a voice for both political and art issues in Depression-era America.

In 1906-1907 Benton began studying painting at the Chicago Art Institute, and the following year he continued his studies at the Académie Julian in Paris. In 1912 he moved to New York where he was involved in the early abstract art scene, and where his works were displayed in exhibitions like the Forum Exhibition of 1916, which was his first public exhibition. During his “modernist period” in New York, 1912-1918, Benton worked as a commercial artist, set designer, and for the early film industry as a portrait and reference artist at Fort Lee, New Jersey. He also joined the People’s Art Guild, through which he was given a position as gallery director and art teacher for the Chelsea Neighborhood Association. In the subsequent years, as Benton matured as an artist, his style became less abstract and more representational. His first works done from observation were drawings, shown at the Daniel Gallery in 1919, which depicted daily activities of the Naval base in Norfolk where he was stationed after his enlistment during World War One. In 1922 his reputation was enhanced when he sold a work to the influential Philadelphia art collector, Albert C. Barnes. He eventually secured a commission for a mural painting titled America Today (1930-1931) at the New School for Social Research, where his drawings were exhibited in four groups; “King Cotton,” “The Lumber Camp,” “Holy Roller Camp Meeting,” and “Coal Mines.” Around the time of America Today’s completion Benton met John Steuart Curry and, soon after, Grant Wood. His association with the two American Scene painters, along with the 1934 Time magazine cover story about Benton, established his reputation as a Regionalist painter. He wrote about his, Curry’s, and Wood’s public identities: “We came into the popular mind to represent a home-grown, grass-roots artistry which damned ‘furrin’ influence and which knew nothing about and cared nothing for the traditions of art as cultivated city snobs, dudes, and aesthetes knew them. A play was written and a stage was erected for us...We accepted our roles” (Gruber 15). Benton not only accepted, but also exploited his role as “Ozark hillbilly” to capture media attention and interest. Benton’s identity brought praise along with criticism. His work was often criticized as superficial and provincial, but it was also praised for its cultural synthesis.

In 1935 Benton was commissioned to create a mural for the Missouri State Capitol. That same year he was asked to serve as head of the painting department at the Kansas City Art Institute. This offer gave him a reason to move from New York, where his subjects and conservative style were pointedly criticized by the art establishment inclined to look more favorably on European-based Modernism, back to Missouri, where he hoped to gain more appreciation for his work. (Fath 214). In 1937 he began writing an autobiographical book, An Artist in America, which mainly reported on his travels across America. During this time he also made sketches and paintings for Life magazine, a series of drawings depicting floods in Southeast Missouri for the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Kansas City Star, and painted Susannah and the Elders (1938, The de Young Museum, San Francisco). He garnered significant attention, and caused a widely reported public controversy, for this work because Susannah’s nudity was unsettling to contemporary audiences. In depicting this story from the Biblical book of Daniel, Benton placed it in a modern setting, which destroyed the illusion of historical distance. In 1939 Benton achieved his first substantial success and acceptance in New York through a retrospective exhibition that was first shown at the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery in Kansas City, and from which the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Roasting Ears (1938). After Pearl Harbor, he began a series of war paintings that were purchased by Abbott Laboratories and presented to the U.S. government in poster and book form. These war paintings resulted in his employment by the government from 1943 to 1944 painting and drawing wartime scenes: industrial plants, training camps, and oil fields. The latter years of his career, 1946 through 1961, were filled with both exhibition activity and commissions for mural paintings. His work was exhibited at the Chicago galleries of Associated American Artists; he had retrospective exhibitions at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, New Britain Institute in New Britain, Connecticut, and University of Kansas Museum of Art. He painted the murals Old Kansas City for the Kansas City River Club, Independence and the Opening of the West for the Truman Memorial Library, and depicted the discovery of the St. Lawrence River and Niagara Falls in murals for the Power Authority of New York.

Benton began to slow a bit in 1962 after he developed a bursitis condition. Due to his age and declining health, he began to execute more easel paintings and fewer murals. He traveled often from 1963 to 1965, and some paintings were exhibited in the Missouri Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964, which was followed by exhibitions at Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois and Birmingham Arts Festival in Birmingham, Michigan in 1966. That same year he suffered a stroke and a heart attack. He wrote the final chapter of his autobiography, An Artist in America, the next year. In 1968 and 1969 Benton exhibitions were held at the Graham Gallery in New York, the Library of Congress, and by the Associated American Artists in New York. After another heart attack in 1970, the last five years of Benton’s life were spent completing a mural for the 100th anniversary of the incorporation of Joplin, Missouri, and working on a mural exploring the origins of country music for the Country Music Foundation. Exhibitions of his work were held during this time, including; Thomas Hart Benton: A Retrospective of His Early Years, 1907-1929 at Rutgers University Art Gallery, a retrospective exhibition at Spiva Art Center at Missouri Southern State College in Joplin, Missouri, and Thomas Hart Benton: An Artist’s Selection, 1908-1974 at the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art. Thomas Hart Benton died in his studio located behind his Kansas City home on January 19th, 1975. A major retrospective of his work, Thomas Hart Benton: An American Original, was organized in 1989 by the Nelson- Atkins Art Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

Fath, Creekmore. "The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton: New, Expanded Edition." Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979.

Gruber, Richard J. "Thomas Hart Benton and the American South." Augusta, Georgia: Morris Museum of Art, 1998.

Kristen McArthur/ed.mla 12.2010

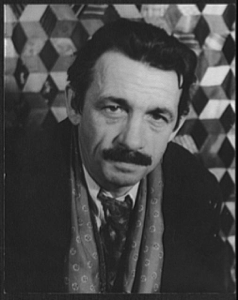

Image credit: Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964), Portrait of Thomas Benton, 1935, photographic print, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., Carl Van Vechten Collection, [LC-USZ62-42517]

American

(Neosho, Missouri, 1889 - 1975, Kansas City, Missouri)

Thomas Hart Benton was a controversial and influential character in both the art and social worlds in early and mid-twentieth century America. He was born on April 15th, 1889 in Neosho, Newton County, Missouri into that state’s most politically powerful family. His great-uncle, also named Thomas Hart Benton, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1820 when Missouri became a state. His father, “Colonel” Maecenas Eason Benton (called M.E.), was a U.S. district attorney for Missouri and was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1896. During his father’s time in Congress, 1897-1905, Benton lived in Washington D.C. He finished grade school there, and was first introduced to an appreciation of fine art at the Library of Congress and the Corcoran Gallery during this time. He also studied art for the first time in Washington D.C. at Western High School in Georgetown. In the March 1, 1937 issue of Life magazine, an article titled “Thomas Benton Paints a History of His Own Missouri,” suggested that Benton’s family history had much to do with his success as an artist: “The Bentons of Missouri are that state’s most revered political family. Missourians say that if Tom Benton were not a Benton he never could get away with such unconventional murals” (Gruber 13). It does seem that Benton’s heritage influenced the way in which he approached his career. As a campaigning politician might do, he made certain that his name and theories of art were publically known and promoted. Through his outspokenness, writings, and large-scale public mural projects, Benton became known as a voice for both political and art issues in Depression-era America.

In 1906-1907 Benton began studying painting at the Chicago Art Institute, and the following year he continued his studies at the Académie Julian in Paris. In 1912 he moved to New York where he was involved in the early abstract art scene, and where his works were displayed in exhibitions like the Forum Exhibition of 1916, which was his first public exhibition. During his “modernist period” in New York, 1912-1918, Benton worked as a commercial artist, set designer, and for the early film industry as a portrait and reference artist at Fort Lee, New Jersey. He also joined the People’s Art Guild, through which he was given a position as gallery director and art teacher for the Chelsea Neighborhood Association. In the subsequent years, as Benton matured as an artist, his style became less abstract and more representational. His first works done from observation were drawings, shown at the Daniel Gallery in 1919, which depicted daily activities of the Naval base in Norfolk where he was stationed after his enlistment during World War One. In 1922 his reputation was enhanced when he sold a work to the influential Philadelphia art collector, Albert C. Barnes. He eventually secured a commission for a mural painting titled America Today (1930-1931) at the New School for Social Research, where his drawings were exhibited in four groups; “King Cotton,” “The Lumber Camp,” “Holy Roller Camp Meeting,” and “Coal Mines.” Around the time of America Today’s completion Benton met John Steuart Curry and, soon after, Grant Wood. His association with the two American Scene painters, along with the 1934 Time magazine cover story about Benton, established his reputation as a Regionalist painter. He wrote about his, Curry’s, and Wood’s public identities: “We came into the popular mind to represent a home-grown, grass-roots artistry which damned ‘furrin’ influence and which knew nothing about and cared nothing for the traditions of art as cultivated city snobs, dudes, and aesthetes knew them. A play was written and a stage was erected for us...We accepted our roles” (Gruber 15). Benton not only accepted, but also exploited his role as “Ozark hillbilly” to capture media attention and interest. Benton’s identity brought praise along with criticism. His work was often criticized as superficial and provincial, but it was also praised for its cultural synthesis.

In 1935 Benton was commissioned to create a mural for the Missouri State Capitol. That same year he was asked to serve as head of the painting department at the Kansas City Art Institute. This offer gave him a reason to move from New York, where his subjects and conservative style were pointedly criticized by the art establishment inclined to look more favorably on European-based Modernism, back to Missouri, where he hoped to gain more appreciation for his work. (Fath 214). In 1937 he began writing an autobiographical book, An Artist in America, which mainly reported on his travels across America. During this time he also made sketches and paintings for Life magazine, a series of drawings depicting floods in Southeast Missouri for the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Kansas City Star, and painted Susannah and the Elders (1938, The de Young Museum, San Francisco). He garnered significant attention, and caused a widely reported public controversy, for this work because Susannah’s nudity was unsettling to contemporary audiences. In depicting this story from the Biblical book of Daniel, Benton placed it in a modern setting, which destroyed the illusion of historical distance. In 1939 Benton achieved his first substantial success and acceptance in New York through a retrospective exhibition that was first shown at the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery in Kansas City, and from which the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased Roasting Ears (1938). After Pearl Harbor, he began a series of war paintings that were purchased by Abbott Laboratories and presented to the U.S. government in poster and book form. These war paintings resulted in his employment by the government from 1943 to 1944 painting and drawing wartime scenes: industrial plants, training camps, and oil fields. The latter years of his career, 1946 through 1961, were filled with both exhibition activity and commissions for mural paintings. His work was exhibited at the Chicago galleries of Associated American Artists; he had retrospective exhibitions at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, New Britain Institute in New Britain, Connecticut, and University of Kansas Museum of Art. He painted the murals Old Kansas City for the Kansas City River Club, Independence and the Opening of the West for the Truman Memorial Library, and depicted the discovery of the St. Lawrence River and Niagara Falls in murals for the Power Authority of New York.

Benton began to slow a bit in 1962 after he developed a bursitis condition. Due to his age and declining health, he began to execute more easel paintings and fewer murals. He traveled often from 1963 to 1965, and some paintings were exhibited in the Missouri Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964, which was followed by exhibitions at Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois and Birmingham Arts Festival in Birmingham, Michigan in 1966. That same year he suffered a stroke and a heart attack. He wrote the final chapter of his autobiography, An Artist in America, the next year. In 1968 and 1969 Benton exhibitions were held at the Graham Gallery in New York, the Library of Congress, and by the Associated American Artists in New York. After another heart attack in 1970, the last five years of Benton’s life were spent completing a mural for the 100th anniversary of the incorporation of Joplin, Missouri, and working on a mural exploring the origins of country music for the Country Music Foundation. Exhibitions of his work were held during this time, including; Thomas Hart Benton: A Retrospective of His Early Years, 1907-1929 at Rutgers University Art Gallery, a retrospective exhibition at Spiva Art Center at Missouri Southern State College in Joplin, Missouri, and Thomas Hart Benton: An Artist’s Selection, 1908-1974 at the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art. Thomas Hart Benton died in his studio located behind his Kansas City home on January 19th, 1975. A major retrospective of his work, Thomas Hart Benton: An American Original, was organized in 1989 by the Nelson- Atkins Art Museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

Fath, Creekmore. "The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton: New, Expanded Edition." Austin: University of Texas Press, 1979.

Gruber, Richard J. "Thomas Hart Benton and the American South." Augusta, Georgia: Morris Museum of Art, 1998.

Kristen McArthur/ed.mla 12.2010

Image credit: Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964), Portrait of Thomas Benton, 1935, photographic print, Photograph courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., Carl Van Vechten Collection, [LC-USZ62-42517]

Artist Objects